One of the few universal truths in fishing, along with “Rods break” and “ Waders leak,” is “You can’t have too many boats.” Had I enough money and space, I’d have a pram, a canoe, a 14-foot outboard-powered skiff, a 16-foot drift boat, and a 20-to-24-foot bay boat. Before you call me on my omission of bladder boats (OK, inflatables), let me say that I still own and use a float tube occasionally on still waters, but I too soon get impatient with finning around and moving nowhere. And yes, the superlightweight versions are fine for fishing hike-in lakes, but for the most part, I’d rather walk unencumbered and fish from shore.

I’ve also fished from pontoon boats and agree that some of them are nice for running polite rivers — or even a few impolite rivers. Still, they seem to me awkward compromises: neither real boats nor rafts. A Water Master or WaterStrider inflatable kickboat is better for moving around than a tube, perhaps better than a pontoon boat for running rivers, and easy to exit for fishing on foot. But like a tube, you’re in, rather than above the water — not my ideal choice. All the bladder boats pretty much mean wearing waders and wielding a pump. To which my response is: Not if I don’t absolutely have to.

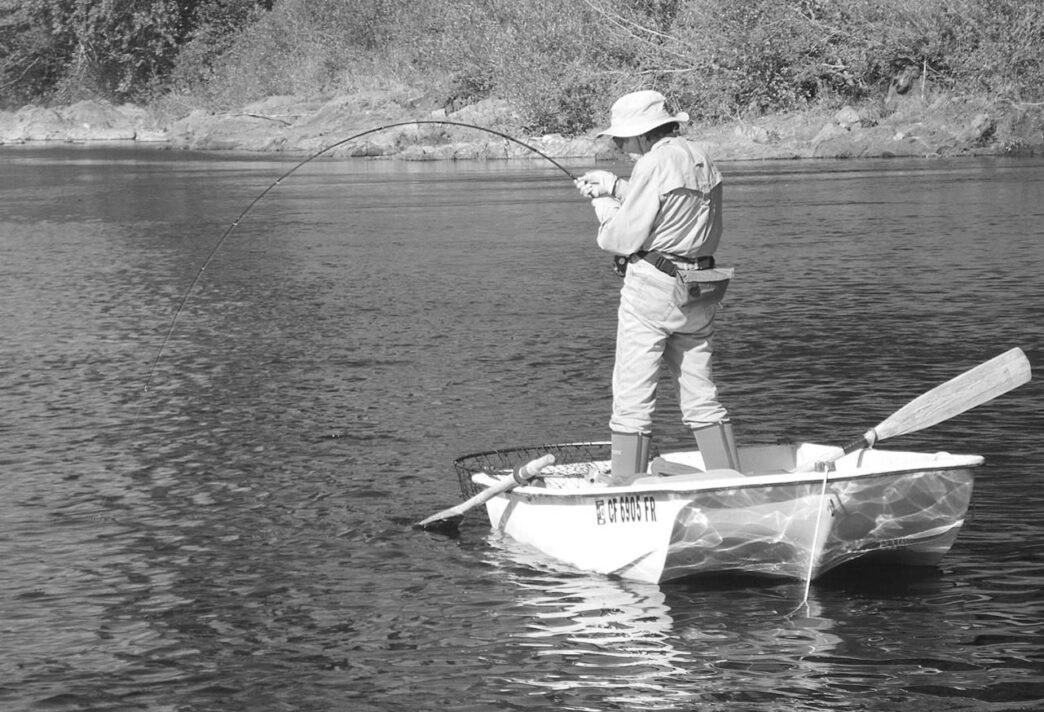

When I want a personal watercraft, an 8-to-10-foot pram lets me fish in a pair of pants and shoes, and I can choose between standing or sitting to cast. (And being able to stand to cast is worth emphasizing, since doing so puts your back cast well above the water while simultaneously letting you get a better look at what’s in the water.) A pram has just enough room for a couple of extra rods and maybe for a fishing dog, gives me easy access to anchors, to a small cooler for food and brews, a dry bag for rain gear, and a pee can that lets me answer nature’s call without going ashore or staining my shorts. As long as I can get a pram to and into the water, it puts me over fish on reasonable rivers and stillwaters all over the West.

I don’t see as many prams on the water as I used to. I attribute that largely to fashion, marketing, and availability. Pontoon boats are hip and more convenient to store than a hard hull. They’re also easier for the manufacturer to ship and for a fly shop to inventory. That counts for a lot in a fly-fishing industry whose options govern many of our choices. But once you get past the ease of storage and transport and can subdue the desire to run Class 4 rapids, a hard-hull pram offers much more. And now that I think of it, a lot of folks carry their inflatables already inflated, which makes them no more convenient to transport or to store than a pram. I don’t expect to change anybody’s mind on this issue, but if you’re intrigued by the idea of a pram, let’s look at the kind of options that one presents.

The Basics of Pram Design

When it comes to materials, you’ve got a choice: aluminum, fiberglass, or wood. Aluminum is durable, can be built so the pram is relatively light (although with some sacrifice of durability and interior amenities), and there are a handful of hull-shape options from which to choose. The downside to aluminum is that it is noisy. Fiberglass offers a quieter and more comfortable surface, is reasonably durable (and generally easily patched), and can be built in numerous hull shapes. But too many glass prams are heavy — around 80 to 100 pounds — which can make them tough for one person to drag around and lift onto a car-top rack.

Wood prams are often more expensive initially, but are quieter on the water than either aluminum or fiberglass. They can be built so they’re very light and in useful hull shapes with contemporary construction techniques — and indeed, can be built at home by an angler who has reasonable tool-handling skills and some work space. Wood requires more maintenance and is arguably less durable than either aluminum or glass, but even without an exterior skin of epoxy resin and fiberglass cloth, a wood pram is still surprisingly strong. Anything but catastrophic damage can generally be repaired. These things noted, though, material probably shouldn’t be your first consideration when thinking about a pram. The first thing you need to decide on is hull shape, which will determine where and how you can best fish a pram. The traditional pram shape has both a square stern and a square bow, the latter a bit narrower and rising somewhat farther above the waterline. Because the bow isn’t pinched into a V, it offers a good deal of room for a given length. The V-bowed hull of the traditional small rowboat sacrifices room, but its finer entry point can make rowing into waves easier. My guess is that an 8-foot square-bowed pram has about the same amount of room inside as a 10-foot V-bowed boat.

A flat-bottomed pram such as a johnboat is fine for most stillwater situations. It’s also generally capable of drifting rivers that contain nothing hairier than an occasional piece of Class 2 water. Johnboats row adequately, though not really well. They also generally have a low enough freeboard (the distance from the waterline to the top of the gunwale) to present a small wind target. That’s a big help both when rowing and when keeping anchored when it’s gusty, but it’s iffy when drifting water with any bounce to it. All but a few have bottoms wide enough to allow you to stand up and cast without feeling like you’re on a tightrope.

A skeg or skegs, narrow fore-and-aft strips tacked to or molded in along the bottom of a pram, will let you track better and may protect the bottom a bit. Their downside is that they make it tougher to maneuver quickly when drifting because of the lateral resistance to turns that they set up. Prams with a bit of a fore-and-aft V to the bottom also aid in tracking, but demand a bit of a balancing act when standing to cast.

There are lots of old johnboats around from outfits such as Sears and Montgomery Ward, and occasionally, you’ll find one for sale used. They’re not great and are generally pretty beat up, but they’ll do. Valco used to make the 8-foot and 10-foot aluminum prams of choice back in the day, and you can still find them on the used market for anywhere from $500 to $1,000, depending on how greedy or desperate the seller. They were stocky little buggers, but they were built to take abuse. A minor drawback was that their multiple seats took up a lot of room. Wide-beamed aluminum prams originated by a company called Metal Head and knocked off by a couple of other aluminum builders in Northern California and Oregon are also occasionally to be found on the used market. They’re light, very stable, and a boat of choice for some North Coast salmon and steelhead anglers. None of the companies making those boats are in business anymore, alas, and even second-hand and third-hand boats tend to go for close to $1,000, if you can find one. If you want aluminum and you can’t find something used, you’ll have to look at current production prams such as Klamath’s Jac Boats, and the johnboats by Lowe, Lund, SmokerCraft, and other manufacturers.

Fiberglass prams with bihull or trihull bottoms used to be pretty popular: the old TP&Ls, Outbacks, and some by Columbia come to mind. Their advantage was incredible stability and a lot of room inside. The downside was that they rowed like bars of soap and weren’t very maneuverable when drifting rivers, due to the multihull bottom. You can still find them on the used market occasionally, but take a close look at the bottom. If the gelcoat and glass are badly worn, the layup has inevitably sucked up water, adding weight. That can be fixed, but work is work. Recently, Bill Kiene put me onto Classic Craft, a company that makes new versions of these prams in Northern California. If stability when casting is your thing, check them out at prams.html.

New fiberglass prams are also available from Spring Creek Prams of Tonasket, Washington (http://www.springcreekprams.com). The 8-foot Stillwater Classic and the larger and deeper 8-foot and 10-foot Hoppers and Hopper IIs have established themselves as fly-fishing standards over the past 15 years or so. They’re not cheap, and options to customize the pram add more to its cost. But Spring Creek prams are well-made boats that combine stability with nice behavior when rowed. Remind yourself that few good things are inexpensive. Spring Creek also offers some nifty wood prams in assembled, but only semi-finished form at a pretty reasonable price. Shipping, of course, increases the cost for any boat not available in your immediate neighborhood.

Add a little freeboard, a little beam amidships, put a little rocker in the bottom of a johnboat to aid maneuverability, and you’ve got a drift pram that fishes still waters just fine, but can also handle and maneuver in Class 2 and most Class 3 rapids decently. It won’t, however, track as well when rowing in a straight line as a boat with a flatter bottom and longer waterline, and the higher freeboard will blow you around more in a breeze.

A few driftboat manufacturers — Don Hill, Ray’s River Dories and Koffler come to mind — make 8-foot and 10-foot minidrifters that are basically truncated drift boats. The 10-footers will fish two anglers, but are easily handled by one. Their drawback is weight — most are well over 100 pounds — which means trailering, rather than cartopping, though as I grow grayer, that seems as much a benefit as a curse. Compared with a bare-bones Metal Head, Valco, or TP&L, a fully tricked-out minidrifter is the equivalent of a Chevy Suburban.

Length

With regard to a pram’s length, you have to choose between portability and comfort. Some 8-foot aluminum prams — which is as short as I think is comfortable — such as those made by the old Lite Boat company and some old johnboats — weigh less than 60 pounds and can be lifted and moved around by a single person pretty easily. But even the lightest 10-footers will generally weigh in at 75 pounds or more. Go much over that weight or 10 feet in length, and a pram becomes a trial for one person to lift onto a roof rack or easily drag around, though it clearly can be done. You also may be able to fit a larger, heavier pram in the bed of a pickup or the back of a big SUV. I gave up on cartopping a couple of years ago when it became too much hassle to get the 8-footer I was using onto the 80-inch-tall roof of my VW camper. A very light trailer that I found on Craigslist solved the transportation problem and also works fine with my 9-foot 6-inch drift pram. Friends with other prams have bought trailer kits from Harbor Freight that require a little bit of time and effort to assemble, but do the job quite inexpensively ($300 or so). You want the one with 12-inch wheels, not the one with 8-inch wheels. See http://www.harborfreight.com/1195-lb-capacity-48-inch-x-96inch-heavy-duty-foldable-utility-trailerwith-12-inch-wheels-90154.html.

Building Your Own

Modern stitch-and-glue plywood construction methods make wood prams of various shapes, from tiny rowboats to more complicated drift prams, a reasonably easy job for someone even minimally competent with woodworking tools. This construction method, popularized by Dynamite Payson twenty or so years ago in his book Build the New Instant Boats, omits the complicated lofting, assembly jigs, ribs, and metal screws normally associated with wood boats. In brief, you use a full-size pattern to trace out pieces for the bottom, sides, transom, and bow on a sheet or two of 3/8-inch or even 1/4-inch marine plywood. You then cut the pieces out with a Skilsaw, and “stitch” them together every three to four inches using wire or plastic ties. You then coat the inside seams with a putty of epoxy and sawdust, much as you’d glaze a window. When the putty is dry, you remove the ties, then overlay the seams inside and out with epoxy-coated strips of glass cloth, effectively “gluing” everything together. You attach interior seat sections in the same manner. The resulting connections are stronger than the wood on either side of them, and the interior of the ribless boat comes out very clean. If you’re interested, there’s a tutorial on the method at

http://www.boatbuildercentral.com/howto/sg101.php#.UV-PDBnxV4s.

For the past year, I’ve been running a 9-foot 6-inch drift pram built with this method, and I love it. I’ll confess that I found my pram already built, unused, and at a price cheaper than the cost of materials, which I figured would run me about $400. It weighs about 110 pounds, so I trailer it, but it rows better than an 8-footer, has a ton of room, drifts nicely in surprisingly bouncy water, and has excellent stability. There are scads of stitch-and-glue pram designs available from Web sites such as Bateau (http://www.bateau.com). There are also a bunch of YouTube videos detailing the building of them.

What sort of things should you look for in an ideal pram? I think 8 feet is the minimum length, but no longer than 10 feet. You’ll want a bit of rocker for maneuverability. And unless you have the agility of a gymnast, you’ll want an absolute minimum bottom width of 36 inches. You’ll also want to make sure the midships area of the boat is flat enough to stand in without continually having to do a balance dance. I’d also look for something with at least 13 inches of freeboard, in part for safety, but also to put the height of your oars comfortably above your knees when you’re rowing. If you’re constantly banging your knees with your oars, extended height oarlocks are available that add an inch or so. It’s also useful to have a pram with seats far enough apart to stretch your legs out a bit when rowing.

Seating

Seats in a pram are themselves an interesting issue. Most aluminum johnboats have at least two port-to-starboard seats, inside which there’s some kind of floatation to keep the boat from sinking if you swamp. But seats take up deck space and can make for tough standing, as well as for cramped rowing, if they’re too close together. Most aluminum drift prams — the Metal Head clones — have but one seat that you can move a bit fore and aft to get the right balance for rowing. Generally, however, boats with that type of seat don’t include any floatation, so if the boat swamps, it will sink pretty quickly.

A few prams — new Spring Creeks and some wood boats, among them — do away with a seat in favor of a pedestal on which you sit to row or cast. The inside of the pedestal also serves as storage and if watertight provides some floatation. Pedestals clear a lot of clutter and are favored by many anglers. I still prefer traditional port-to-starboard seats that let me separate gear from where I want to plant my feet. My ideal configuration is a stern seat 8 to 10 inches off the transom so I have a space for storing an anchor and a pee can and one other seat amidships from which I can row. Between it and the bow goes all my other stuff in a plastic storage bin or ice chest.

Options for Rowing

For oars, you can go light or heavy, cheap or expensive, wood, aluminum, or composite. Except for the cheapie aluminum stuff, the lighter the weight, generally the higher the cost. Whatever your choice, buy a length that takes into account the beam (width) of your pram, that gives you a good sweep when rowing, and that stows easily in the boat when shipped. On a pram 56 inches wide, 6-foot oars make for ineffective propulsion, while 7-footers will scoot you along very nicely.

Wood oars are the standard, and the economy versions by Carlisle, sold all over the place, including various Web sites such as Amazon.com, are decent and reasonably priced at about $40 each for 7-foot oars. If you want the best, Sawyer (http://www.paddlesandoars.com) offers light, well-balanced wood and composite-shaft oars, but the price starts at well over $100 each and goes up very quickly from there. I covet a pair of Sawyer Lights, but it’s probably overkill from a budgetary point of view. My feeling is that most aluminum oars, particularly the takedown, two-piece variety, are best reserved for pontoon boats, though if long and sturdy enough, they’ll work in a pinch.

I prefer U-shaped oarlocks that use split rings to keep the locks in the lock mounts, rather than the round locks that stay on the oars. Either will do fine, but it’s easier for me to drop the oars into the locks than to drop the lock pin in that tiny 3/8-inch hole in the oarlock mount, where it wants to bounce out. Rubber or leather stops on the oars that prevent them from sliding past the point where they row most efficiently are an inexpensive addition.

Anchors

You’ll want to outfit your pram with two anchor releases: a pulley of some sort at the bow for a main anchor and a second jam-cleat or cam-cleat release at the stern for another anchor to steady you in current and wind. I’ve found 15-pound pyramid anchors to be the best in rivers, though a lighter stern anchor of 10 pounds will usually work. Mushroom-shaped anchors of 10 pounds or even less generally work fine on still waters.

The Scotty Company, of downrigger fame, makes an inexpensive, removable pulley/davit release called Anchor Lock that works very well and that can mount either flush with the deck or inboard. The Scotty website product listing (http://www.scotty.com) doesn’t show it, but if you can download their catalog, it’s there on page 32. Spring Creek Prams sells them, along with another little removable davit release called the Pocket Puller that drops into an oarlock socket. Both are fine for stillwater use or for a stern, steadying anchor, but probably not strong enough for bow use in any current. For use up front, I like something beefy, like the two-part Dierks removable davit/pulley. A bracket attaches to the boat, and the davit pulley itself drops in, extending out 6 inches or so from the bow. That lets you pull up the anchor without bringing it and a mess of weeds or mud into the boat when moving around. The device shown at http://www.dierksanchors.com/images/1.JPG is meant for V-bowed boats, but they’ll make you one to fit the flat bow of a pram, if you contact them.

Motors

How about a motor? They’re nice when moving upstream or into a wind, but they have obvious drawbacks in that they take up space and add weight, at the very least. With electrics, there’s the issue of where to put the battery and how to manage the cables, though quite a few prams have provisions for battery storage under a seat, and some, like Spring Creek’s, have battery cables and connections built into the floor, which prevents a lot of tangles.

Gas outboards require fuel, which can mean a fuel line and an external tank: annoying if you’ve got only 8 to 10 feet of space inboard. A number of small, 2-to-4-horsepower motors have integral gas tanks that are terrific space savers, but only the four-stroke Honda 2.3 is lighter than 30 pounds, and it’s a couple of hundred bucks more costly than the heavier four-stroke motors made by other manufacturers. An older motor bought used is likely to be a two-stroke, which needs an oil/gas mix and can be difficult to fix when you need to find parts. Nothing’s easy, right? And with any motor, you’ll need to register your pram with the state and display a registration sticker and number along the bow.

Accessories

For accessories, along with anchors and pulleys, you’ll want a couple of 25-to50-foot lengths of decent anchor line. That means a good braid, not the shiny nylon crap that stretches half its length under load. Add a seat cushion, maybe a piece of indoor/outdoor carpeting for the deck, and, of course, a personal floatation device for everyone in the boat. A seatcushion PFD makes you legal most places, but might be hard to grab if you go overboard. I’ve taken to wearing a self-inflating CO2-activated PFD that looks like a horse collar and inflates automatically upon immersion. Similar versions inflate with the pull of a cord. Just about every boat-supply shop — West Marine, for example, and Cabela’s for that matter — sells them. But they don’t do any good if you don’t wear them. It took me a day or so to get used to mine, but I became religious about it after a friend dumped one day and had a hell of a time before another boat grabbed him.

That’s the pram story as I see it. They’re not for everyone. But for the angler who wants a personal watercraft in which he or she can stand to cast, not wear waders, never have to wield a pump, and who doesn’t mind cartopping or towing a very light trailer, they’re ideal. That noted, owning one won’t cure your lust for more boats. And by the way, rods still break and waders still leak.