“Many men go fishing all of their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after,” wrote Henry David Thoreau.

I suppose that’s true. Of course, some do know why and treasure the reasons.

To wit: the pleasures of fly fishing are themselves enough to rouse us to venture out, but sometimes — for some of us, anyway — there’s an urgency to getting away from lives filled with unquiet desperation. A trip is a chance to escape into the wildness of water and sky, where for hours or days, the pursuit of prey will insulate us from civilized cares. Herbert Hoover called this “the great occasion when we may return to the fine simplicity of our forefathers,” but John Gierach captures our faith in taking flight: “The solution to any problem — work, love, money, whatever — is to go fishing, and the worse the problem, the longer the trip should be.”

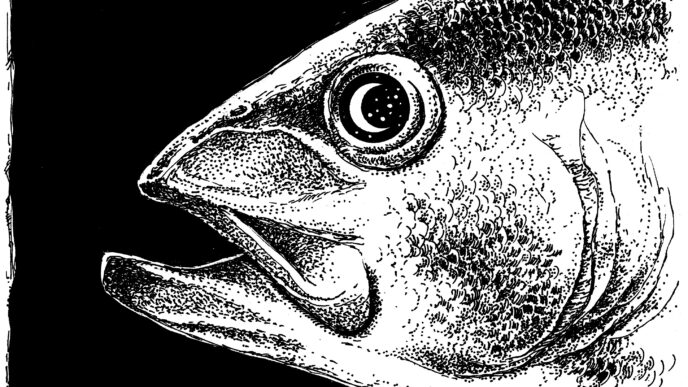

Of course, we hope to catch fish — and hope is a wonderful thing to feel — but catching’s a gamble, other benefits are certain, and the chance to lose yourself in fascination can be heady. It is for me, and for months this winter, I was sure the puzzles presented by trout would divert my attention, momentarily, from the machinations of a long-term-care insurance company that the New York Times described as “habitually” denying benefits to policyholders such as my mother.

Substitute a trial of your own; you get the idea. And maybe you, too, have been or will get lucky enough to find respite from your trials.

Dress warmly, if you try in January. Keep your expectations reasonable. On still waters where I need to break bank ice to launch, I don’t anticipate caddis blizzards. In fact, an Internet search on cold-weather hatches on my local lakes turned up sites dedicated to wood ducks,“seagull facts,” and “Recreational Fishing for Crayfish,” although the season doesn’t open until May. This paucity of flying bugs is the reason why nearly all of the very few fly fishers I meet in this season troll big Woolly

Buggers behind float tubes. They believe they’re imitating minnows, leeches, or dragonfly nymphs, also that by kicking vigorously, they can delay hypothermia. “Doing well” for such die-hards means a couple of tugs a day, with a trout or two landed.

I’ve been in their waders, so to speak. But after half a decade, I found myself weighing these fish and the thrills they provided against my bladder contents and the stresses they provided, so I now choose to angle from a crummy plastic boat that a club I belong to keeps locked by the launch ramp. I’m still cold, but more mobile for longer, better able to fish shallow flats from on high, and, as it happens, the lake isn’t a source of drinking water for anybody I know.

I also choose to fish midges, dry, most of the time, even if this really means trading tedium for frustration. A size 18 or 20 Griffith’s Gnat is tough enough to see in the autumn of life, but on days when you can’t feel your fingers and your pupils have frozen while staring into some middle distance, spearing 6X tippet through the hook eye can take as much time as I spent tying the fly. “Talk to the hand” takes on new meaning when I’m swearing at one of my own.

But that’s all right. It really is, because while knotting up I’m so focused that I’m barely disturbed that I might have bitten off a small piece of tongue . . .

… and, sure as hell way too engaged to rage about a corporation that has now delayed payment for care for as long as one allegedly did in a California case, William Hall v. Senior Health Insurance Company of Pennsylvania — the latter known by the acronym “SHIP,” except by policy owners who tweak the last consonant.

No, really. I’m quite serious about the importance of diversion. Knot finished, my concentration remains intent as I search for rises or water where I’m likely to find some. That focus will last for hours, and even if it strays, won’t go far, and rarely to subjects I need to avoid for a while.

This is a fine relief. It’s also a phenomenon common to a couple of fishing partners with whom I share banks or boats.

Sean, for example. During our last trip to this destination, he talked about the department store where his wife works. Not long ago, she had so dramatically increased sales that her supervisor asked her to open a brand new department. Once this was established and thriving, the supervisor began carefully scheduling hours so he could terminate the health care coverage on which she and Sean relied.

Bit of a problem, when you’ve just turned 60, and we’d talk about it again on the drive home. But this topic never came up once during three chill hours of nadase-nada fishing. Instead, we changed flies, tactics, and locations, discussed a flock of Canada geese that Sean alarmed with pitch-perfect calls, then exchanged reports of studies we’d read revealing the astonishing intelligence of crows. That led to contemplations of human sentience, which — after a long diversion into the observations of an ethnobotanist who’s researched and imbibed many of the world’s most alarming hallucinogens — we applied to our fishless dilemma.

No luck. If our vast experience had failed us so far, I remarked, at least a popular tool of logic could explain our failure.

“The fish are all dead,” I announced. Sean lit a pipe in the silence that followed, which extended just long enough to suggest I should add emphasis and detail. “Maybe they migrated out through the marsh, but it’s more likely they froze in that last cold snap, so now are rotting in silt. Frankly, I think it’s tragic.”

Sean nodded in a way that did not necessarily imply agreement. At the same time, he exhaled a puff of smoke that eddied around in an intimate cloud that smelled like vanilla, leather, and, for a sudden warm moment, my father. Then he said, “You think.”

“I do. I just make sure not to think too hard. Occam’s Razor is the tool smart guys use these days — you can check Salon.com. ‘All other things being equal, simpler explanations are generally better than complex ones.’”

“I see. No other possibilities?” “Could be. But they are too complicated to consider when I can’t feel my feet. Which by the way, is an improvement. Also, I’ve pretty much stopped shivering, so we’re sitting pretty over here.”

“Good. Because you have been saying you’re sure we’ll see midges soon.”

True. I was convinced of that, also that Occam’s Razor, while a marginally useful device, is today used too often as a blunt instrument by dullards, or as a weapon by people disguising lies.

I mentioned that to Sean, which ordinarily would have led into a righteous diatribe about corrupt corporations or government agencies or political parties. But it didn’t at this moment, because I was sure again that midges would come off and determined to be ready when this happened. They came. Not many, and they were ovipositing, flying tight circles above the surface, but the trout came alive to chase them. I greased my leader almost all the way to the Griffith’s Gnat, prayed for the knot, then began casting to rises and twitching retrieves. A dozen trout decided that all other things being equal, my fly was food, and while my forefinger let slip nine strikes, three hooked themselves. Sean, who’s not convinced that stripping a bug across the top is “dry-fly fishing,” elected to let a floating attractor pattern lie dead. Although that drew fewer strikes, it allowed him time to call a Canada drake almost into the boat, where its down, plucked and stuffed inside our vests, would have been sincerely appreciated.

We left content. Also, hypothermic — “I think we pushed things a little,” Sean admitted in a rare burst of wild speculation — so it took a while for the truck heater to cook off what felt like a dense blue layer of brain fur. By then, we were well on the way home and had already returned to topics we’d mercifully forgotten for a time.

And “mercy” is just the right word.

A month or so later, another friend needed some.

For years, Don’s been struggling to find a day of his own while running a business, fathering three kids, and caring for 90-something-year-old parents who live independently only because he’s around to help every day: “I don’t mind” is the mantra of Don’s middle age. So is the “Sorry to do this again” that has prefaced apologies for canceling fishing trips. I don’t mind this, but the last time I ran into him, I was bothered by a new stoop to his shoulders and circles under his eyes. So when a weather forecast promised a fine day, I gave him a call. Close thing, but when Don’s wife stepped into the gap, his “Hell yes!” hurt my ear.

Gorgeous day, clear and not too cold. Don was grinning when I picked him up. “Hope we catch something, but God, I’m just so glad to be getting out.”

I’d remember that line later.

Same lake, same drive — and once again, a dark conversation filled the cab. We’d invited a third pal along, without success. That was sad: Mike’s life and luck had gone south when his wife, Wendy, began slipping into dementia at about the same time as my mother. Both were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s syndrome. In my mother’s case, this was dead wrong. She had Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, so after a year of suffering, she woke up from a lumbar bypass procedure completely coherent. Wendy, however, was not so lucky, and her doctor told her and Mike that they needed to accept the inevitable.

Neither was ready to surrender, so Mike hunted the Internet, looking for alternative Alzheimer’s treatments showing promise. That’s a complicated world to navigate, but he and Wendy consulted a licensed naturopath to guide them, and a thousand hours of research seemed to pay off when supplements appeared to reverse a decline that at one point had left Wendy unable to use a calendar or drive: six months later, she was back behind the wheel, shopping for groceries and cooking great meals from complex recipes.

That progress ended when an infection put Wendy into the same hospital where my mother had been misdiagnosed. Her furious doctor attributed her condition to the supplements and insisted Mike agree to restrict Wendy to medications approved by the FDA. That was a sentence to slow death, but when Mike refused, the doctor instigated an investigation by Adult

Protective Services. Although it took only an interview for that agency to decline to pursue a case, the idea that he could lose Wendy shook Mike hard. He realized he must consider not only every supplement’s potential to help his wife, but the legal implications of taking these if anything happened to her. Reluctantly, he and Wendy agreed that she would use only those recommended on the hospital’s discharge summary, even though this meant discontinuing one of the most promising.

That was then. Now she was losing ground. Mike was not going fishing anytime soon. And the point of inserting this digression is this:

Don and I were worried about Wendy . . . also about Mike, who’d cut back on everything in life beyond Wendy’s care, including work. Don had helped him with legal issues; I’d edited a medical appeal; we met him for coffee, talked him through nights of exhaustion and despair . . .

. . . but somewhere on our walk into the lake, Don and I began thinking and talking trout. Soon we were busy scanning for the water for rises and bushes for bugs, then the shallow water at the boat launch for fry and minnows. Setting up the little boat, untubing rods, checking leaders — all the rituals of rigging: so it begins.

So it continued. We plumbed a channel for a while, had one hit — maybe — then rowed across the lake toward a lee shore where breezes often pile up thin scum slicks. Midges began to appear here and there — egg layers again, orbiting beneath a bright sky above a surface today almost glassy. Trout took a few of these, but the greased Gnat didn’t tempt any in these conditions. Neither did a series of other dry chironomid patterns, fished on top, then in the film, then submerged.

This went on for three or four fishless hours — a fair slice of time in a small boat. Don and I talked here and there, but not about anything more charged than this new rod or that old one, how fine it felt to sit under the sun after so long, and fishing memories. “Didn’t you get a brown here two years ago, over by those tules? What was he, eighteen inches?” “Or fourteen, though he might be eighteen now.” We strayed to innocent topics: how a daughter loved her horse, one son exotic cars, another a young woman he met in Kenya. Light stuff, all this, and subject to immediate interruptions: “Yeah, he met her online, and a year later flew off to Africa — Hey! That looks like a school over there — smutting, aren’t they? And coming this way. Let me see if I can make this cast . . . brother!”

Washington Irving wrote: “There is certainly something in angling that tends to produce a serenity of the mind.” I don’t think “serenity” describes the excitement fishing has given me most of my life, but this day, I came close.

Unless you count frustration, of course. The trout puzzle really wasn’t complicated. Tied flies don’t actually fly, unhappily, unless you can dap a brushy pattern with a floss line — and if I’d thought to bring one, today, that technique would take wind we didn’t have. So now what?

I kept asking that question, but not with desperation. On a frustration scale of 1 to 10, mine registered between 2 and 4. Don’s was even lower. “Maybe we’re getting old,” he said, laughing. “Missing some of the blood lust. But to tell you the truth, I wasn’t counting on catching anything, and it’s so good just to be out here.”

That was true. But when the sun’s pale belly touched the snow cap of a hill, my frustration scale escalated to FS 4.7, mainly because I’d started to believe I was missing something — that I’d faced a dilemma like this once before and solved it. Where, when, how? It’s a pity my memory has no keyword search function. But maybe not, because I’d have inputted “stupid midges flying around,” which wouldn’t have helped and might have distracted me with invaluable crawdad-fishing tips.

Flying ants, that was it. Not in the air, but lying dead and dying in a mountain lake where a thunderstorm had knocked down thousands from a mating swarm. Brown trout had been feeding on these so selectively that it looked like they were counting legs, or maybe leg joints. Nothing in my fly box came anywhere close to matching the size, shape, or color of these. If I can’t find anything they like, I remembered thinking that day, what about something they dislike a lot? An offering that would not only break their focus, but provoke them.

A baby brown trout pattern turned a dozen fish heads that day, and the strikes were savage.

This day, I didn’t want shock and awe, but something that would surprise surface feeders without spooking them. A fly that would prompt a “What’s that?” reaction, followed by “Oh yeah — I eat those.”

Perhaps your ruminations don’t include dialogue. Mine don’t always, but I decided the right answer wasn’t one of the size 8 or 10 Woolly Buggers that fishers trolled deep. I picked that pattern, but one tied on a medium-shank size 16 hook with a 3/32-inch bead head that when fished on a greased leader would barely sink the marabou. It might be a minnow, a small leech, a dragonfly nymph, or nothing specific at all.

Cold set in as the sun dropped, but the fishing was hot for an hour. We landed half a dozen 10-to-12-inchers, plenty of fun on 4-weights, and missed twice that many. Of course, we stayed out too long. “I’m starting to slur words,” Don said, then laughed again, now in a higher pitch than before. Or lower; I can’t remember clearly. But I do recall an idea that occurred to me as we rowed in, while I was wondering if I’d really figured something out or simply stumbled onto an acorn.

While I wanted to believe that I’d solved the puzzle, what was confusing now was that I felt no need to convince myself of that. There was something oddly appealing — reassuring, even — about the idea that I’d just gotten lucky. I wondered why that might be, since I pride myself on moments when I believe observation and rational thinking have made a fish take.

Luck’s a strange lady. I’ve known people she’s seduced, the kind of gamblers who don’t count cards or calculate —folks who pull slot machine arms for hours or every week circle numbers on lottery tickets. While my father was the most rational of men, when talking about luck, he would shake his head and smile around a pipe stem. “I don’t know how it works. I just know it does, or doesn’t.”

No doubt it’s a part of fishing. The best fishers will do better than the rest of us, trip after trip, because they maximize odds and minimize mistakes that ruin opportunities. Even so, if every cast caught a fish, I doubt they would bother to try.

So where does luck fit into fascination? Don’t we make every cast with an expectation that somewhere out there we might find a fortune that matters to us?

I’m sure I’d have left these questions if luck, as coincidence, hadn’t interfered.

An e-mail arrived linked to an essay titled “ Why Fly Fishing Is Not about Luck.” On a whim, I entered “Fishing and Luck” into a search engine. I liked a quote from Ovid that I found: “Let your hook always be cast; in the stream where you least expect it, there will be a fish,” but the majority of maxims, most not specific to fishing, supported the obvious idea that success is all about planning, preparation, and skill. While some described a balance — “Luck is what happens when opportunity meets with planning,” opined Thomas Edison — a surprising number crucified those who would cast their bread upon the waters without taking its temperature and testing its pH.

I reread two of these soon after Mike’s situation turned surreal. “Shallow men believe in luck. Strong men believe in cause and effect,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, and somebody named Timothy Zahn amplified this judgment: “Luck is merely an illusion, trusted by the ignorant and chased by the foolish.”

“Ralph, Timothy,” was how I addressed a message I wished I could fire into the ether. “Got your messages. Send edits when your wife comes down with Alzheimer’s.”

I’ll make this brief.

A friend of Wendy’s brought her a bag of grapefruit and a half gallon of fresh-squeezed grapefruit juice, all of which Wendy consumed. Mike thought nothing of this; he’d researched all of Wendy’s supplements, but not the food interactions of medications that her doctor had prescribed for years. Among these was simvastatin.

Mike had no idea what could have caused the symptoms that struck Wendy over several days: fatigue, fever, agonizing pain in her legs, dark urine suggesting kidney failure. Three times he took her to the emergency room, where doctors proposed conditions including possible pneumonia, but discharged her after just hours. When she continued to worsen — reduced to the mental functioning of a terrified toddler — Mike rushed her to another hospital.

As always, he arrived with a list of the supplements Wendy was still taking. Although none were known to cause her present symptoms, the doctor instantly concluded that one or more had caused this crisis . . .

… and that Mike was responsible.

It took him three days to discover that the combination of grapefruit and simvastatin could be lethal and that every one of Wendy’s symptoms are specifically identified on lists of adverse reactions. By then it was too late. Occam’s Razor had already changed Mike and Wendy’s life forever.

The doctor would not even speak to him. She had relayed accusations against Mike to Wendy’s relatives. In an hour when Mike was absent, they had convinced her to sign over to them a power of attorney — a document she had refused to sign a month earlier. With that in hand, they ordered the hospital not to discuss Wendy’s care with Mike and to deny him access to her records. Then they discharged Wendy from the hospital, refusing to tell Mike where they had taken her.

Mike contacted an attorney. The caution he received was stern: not only had he lost legal custody, but two doctors would assert that his care had inflicted injuries on Wendy that required hospitalizations. Mike could only wait, hoping his wife would recover enough to insist she return to him.

She has not. Mike received divorce papers, then a demand from the relatives to vacate the house he shared with Wendy. These were followed by notice of an application for a restraining order alleging neglect and multiple crimes. Then came a court summons to face charges for domestic felony assault, inflicted by helping Wendy take supplements.

I wish I could write that Mike’s trials had a happy ending or at least describe a fly-fishing trip that helped him to escape this nightmare for hours. Not yet. Maybe later.

No. Wait.

Certainly later, and if you’ll forgive a return to ideas that might seem trivial for a paragraph or two, I’ll tell you why I believe that.

Fly fishing is how I got to know Mike. In a decade, we partnered on fifty trips, I’m sure, and from the first, it was clear that Mike was one of those anglers too optimistic and engaged ever to give up. Not catching fish didn’t mean failure to him, but opportunity — a reason to read more books, scour magazines, and invent flies. Once, steelhead fishing, I saw him skunked for four days straight — not a strike — and he still started early every morning and fished to dark-thirty. Softspoken and thoughtful, almost impossible to anger; as a fisher, Mike is relentless.

Also, as a husband — relentless. When told his wife would die slowly, losing her mind over years, he refused to surrender hope.

He’s been casting for a cure.

Mike can’t save Wendy now. Maybe he never had a chance. What’s happening is brutal — and God, he sounded like hell last night. Even so, I don’t think Mike will give up hope for his own life. I imagine he’ll want to lose himself for a while, to water and sky, wildness and fascination. And when that happens, he’ll understand that it is not just fish he’s after.

Luck.