For the kid, the only constant and reliable aspect of life was that of feeling different. This, and the love of fishing described in worried tones by his parents as an obsession.

He overheard them one evening arguing over the possible wisdom of medical help. A psychiatrist might break this thing up, they said. His father decided that was crap while his mother wondered if, instead of looking at rods and reels or making flies or whatever, he was really, you know, playing with himself.

The kid was pleased to have overheard this exchange because, while it didn’t make him dislike his parents or anything at all that extreme (he had for some time largely regarded them both as imbeciles), it did bring home just how alone he was; and, for all he knew, would always be. It made him further cultivate his estrangement, and work harder at perfecting his own particular contrariness.

His peculiarities — the need to be alone, the compulsion to fish, his avoidance of otherwise normal social activities — were, it was later said, what developed so much character. But that building of character, he thought, also later, sure wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

As years went by, the kid learned to do a passable imitation of normal life. He lived one rather secret life he believed to be his and another which everyone thought was his. The two sometimes crossed and became indistinguishable, but in each there was fishing, which still gave him more pleasure than anything else.

Strangely, the fact that he loved fishing didn’t make him close to others who fished. Increasingly, he found himself to be as at odds with other fishermen as he was with his geometry teacher. In either case he did not become, as they say, a brother of the angle.

He certainly heard a lot and read a great deal about fishing, yet never seemed to come upon any single idea or passage that described why he loved to fish, what it meant to him or just exactly how he fit into the picture, if indeed he fit at all.

He came to understand that certain writers were known as experts at fishing. Some of them had fished every river, lake, and ocean in the world and caught every kind of fish on the planet. They wrote hundreds of magazine articles about it and volumes of books. They could flycast backward and sideways and seemed to have on the tips of their tongues obscure information about optimum water temperatures or lunar influences. They knew the physics of every conceivable piece of tackle. It was true, they were experts, and they probably loved to fish.

But for some it was also obviously a matter of social contact and position. For others it was just a job. For still others it was a kind of power and influence, like money. Some used fishing as a vehicle for their egos. Many seemed to combine a little of all of this.

Something else would frequently emerge, and that was the notion of contest. There was much talk about the challenge of this or that kind of fish. Anglers were pictured sweating and exhausted after taking an enormous marlin or other mythic beasts. The monthly sports magazines endlessly promised to reveal secret ways to Murder Fish in Your Area.

Sometimes the challenge was less physical as one expert or another spent hours, even years, trying to outsmart an especially wily old mossback. This, the kid had always thought, was certainly the most towering stupidity of all.

There was a special watershed where the kid grew up, one he fished again and again. He felt comfortable with it during every season and on any day. He knew its every mood: how the winds blew and how the clouds traveled across the sky. What it meant for the fishing. He knew the colors of spring and fall, the cycles of everything living there. He watched for strange footprints, noticed branches he himself had not broken, and saw what grasses may have been bent by passersby.

He knew this place the way he knew his own reflection. And just as he looked upon his own reflection with the passing years not to see how it had changed, but how it remained the same, so he looked at this place. He thought about duration.

Two things, then, mattered most, and these he realized were the same when he fished as they were when he considered all the other aspects of his life: what had been, and what was. Curious, he thought, that an equal concern for the future was absent.

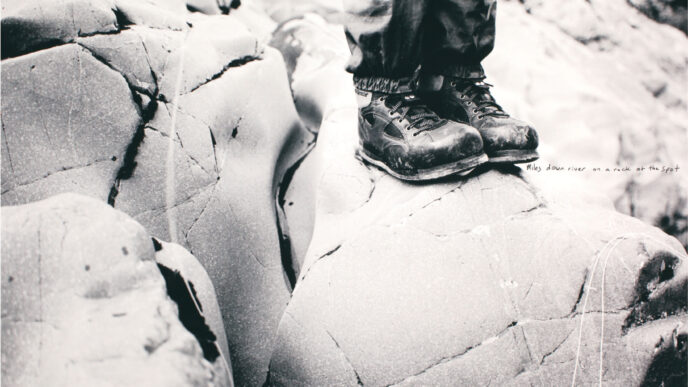

He went to bizarre lengths to learn everything about the part of the stream where he fished. This section was a tidal estuary where, in the fall and winter, the fishing was for salmon.

But the kid frequently went there in the spring and summer when there were no fish and, more importantly, no fishermen. At those times he would take a small rowboat and, using a line and sinker, plumb every square foot of every place he ever fished. The bottom then became a real landscape to him even though it remained invisible beneath the surface of the water.

He watched the tide come in and go out, measured its various heights and watched its swirlings. He picked up handfuls of mud from the bank at low tide, squeezing it through his fingers. He sometimes let his boat drift, letting his eyes slip out of focus until there was nothing but a distant humming, a daydream of patterns like a wall of snowflakes.

Eventually, he began to think of this water as being like the house where he grew up. Since his early childhood the kid had had an ability to visualize almost anything he had seen before. It was how he daydreamed. At night sometimes he would wake up and walk briskly through the darkened house as if he could see. He could stop arbitrarily, reach out and touch any object. He never bumped into things unless they had been moved since he had last seen them.

He walked around in the dark mostly to amuse himself, sometimes imagining various guests at a dinner party. Doing this seemed to give him assurance that he knew exactly where he was.

This was just how he fished. He saw his favorite stream as a room, like the living room at home. He knew the ceiling, the floor, the walls. He imagined the fish in it just as he imagined the dinner guests. The current, if there were any, was simply a breeze blowing through the room.

In the fall the salmon came as they always did. That year, though, they were three weeks early. The kid was there the dawn after the night they came in. He was there because he was always there every day at dawn weeks before there was any possibility of fish. He liked to know exactly the night they arrived.

The first fish that splashed water barely rolled above the surface and he couldn’t locate the sound. But the second leaped clear in an awkward upside-down jump and the kid was looking right at its black, upside-down eye. He shrieked in a long, hysterical way, threw his fly rod far up into the bushes and ran as fast as he could to the end of the beach, chuckling, then turned and ran back. He screamed again, and went over to find his rod.

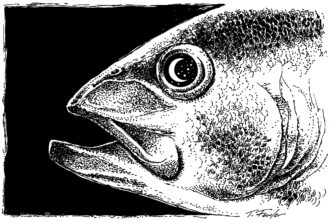

The first salmon took his fly as predictably as sunrise and the kid brought it to hand with ease. He took the fly away from its jaw, held its cheek momentarily to his own, feeling its cold slickness even inside his own body, then let the fish go.

A flock of small shorebirds landed nearby and started feeding on the bank newly exposed by the falling tide. The kid whispered to them but they ignored him, walking jerkily beneath his fishing rod and around his boots.

He fished for hours without a clear, conscious thought. He couldn’t differentiate, nor did he care to try, among seeing, hearing, feeling or acting. He was in the wall of snowflakes; a block of time that was both reality and illusion like a book or symphony. He was in the dark room but it was light. He could see but not be seen. There was wind fresh against his cheek, he knew that. Or was it water?