An interesting phenomenon happens on Sierra lakes and other waters in California and the West. It is the simultaneous emergence of our most common stillwater aquatic mayfly, the speckled Callibaetis, and of another aquatic bug from a different taxonomic order, the damselfly. An angler who has guessed or planned right can encounter a situation in which phenomenal numbers of both insects appear at the same time. This abundance of concentrated protein attracts ravenous trout and occasionally bass and panfish. The fish sometimes lose all semblance of caution, yet they also can be terribly selective. And even if you don’t encounter a major Callibaetis hatch or damselfly migration, these two bugs are present from May through October, or even before and beyond this span, depending on latitude and altitude, and their imitations are always a good bet to try when searching for a fly pattern that will entice fish into a strike.

Both insects are typically found in 20 feet of water or less and depend on aquatic plants for shelter and food. Callibaetis nymphs graze on diatoms and algae. Damselfly nymphs are predatory and feed by ambushing just about anything that they can get into their pinchers.

Callibaetis Mayflies

Callibaetis mayflies, order Ephemerella, family Baetidae, have four stages in their life cycle and can produce as many as three generations in a year, each subsequent generation being a bit smaller as the season progresses. The first-generation duns are matched with a size 14 to 16 fly. Later, they may be as small as size 18. The nymphs are typically 6 to 12 millimeters long (from just under a quarter of an inch to just under twice that), not counting their three tails. Once the duns have molted into adult spinners and have mated, the females lay eggs on the surface of still waters or slow-moving streams, and these typically hatch into nymphs in about six weeks. The nymphs find aquatic plants that provide shelter and harbor food. As these agile creatures graze on algae and diatoms, they molt a number of times, reach nymphal maturity, as shown by a developing dark wing pad, then work their way to the surface in a vertical zigzag, up-and-down movement that can take hours. They are helped by internally developed gas bubbles that reflect UV rays, and eventually, they break through the surface meniscus, sprout wings, which dry quickly, and fly off to waterside vegetation, where the duns molt once again into spinners. Later, they congregate in mating swarms above the water. Within several hours, the fertilized female dips to the water, releases her miniscule eggs and falls depleted to the water’s surface, the cycle completed.

That means that anglers can cast subsurface nymph imitations, then fish the rise with nymphs, stillborns, or emergers on or near the surface, and can go on to take fish with dry flies and spinners that lie spent the film. I call this the Callibaetis Gram Slam and have managed to accomplish it only a few times in a single day.

I look for Callibaetis activity from around 11:00 in the morning into the early afternoon, but no hard-and-fast rules apply. Sometimes the hatch is a late afternoon event. Fish browse the aquatic forests, feeding on Callibaetis nymphs that they knock loose. I look for weed bed edges where I can allow a Callibaetis nymph to fall vertically down the face before I start a slow, intermittent, rise-and-fall retrieve. When the emergence begins, classic head-and-tail rises signify that trout are taking the emerging nymphs or stillborns just under the surface or in the film before their wings fully sprout. Classic-sight fishing tactics come to bear then. (See “The Stillwater Fly Fisher,” California Fly Fisher, January/February 2014). Spinners can fall to the surface in great numbers. Weather determines whether their numbers are significant enough to produce such prolific spinner falls. Calm, warm mornings are best, and you may be able to hear the “gulp” as fish cruise and gorge themselves.

The most impressive Callibaetis hatch that I have witnessed occurred on Nevada’s Smith Creek Lake in early May. Hundreds of thousands if not millions of these bugs started hatching around 11:00 A.M. on a snowy morning when clouds were penetrated by columns of sunlight. We were first alerted by a few exploratory dipping swallows, then thousands of birds plucked the duns off the surface as fast as they could emerge. Our nymph patterns took only an occasional fish, however. Frustrated, for no particular reason, I tied on a black size 12 A.P. Nymph that was weighted with a dozen turns of .020-inch lead. The slight plop of it landing seemed to get the attention of the swirling trout, and there was usually a take on the first pull of the retrieve. Cowpunchers on horseback herded cattle past the small lake toward roundup, and in the middle of the melee, two F-18 Hornets from Fallon Naval Air Station came up the draw at about two hundred feet and ignited their afterburners. It was a glorious day.

Damselflies

Like Callibaetis nymphs, damselfly nymphs inhabit aquatic forests, but also reeds, flooded sagebrush, and other brushy stick-ups. These predators move through the weeds looking for prey that might even include small Callibaetis nymphs, since they occupy the same territories. There are two main groups of damselflies. One is of the Coenagrionidae family, whose nymphs are smaller, ranging from 12 to 25 millimeters (just under half an inch to an inch) in the mature nymphal form. The second group is the Lestidae, whose nymphs can be 18 to 35 millimeters long (just under three-quarters of an inch to over an inch and a quarter), and these are more common. Both have identical life cycles that start with a fertilized adult crawling down a rock, a piece of vegetation, or downed timber and depositing eggs. The eggs hatch into damselfly nymphs, which, like the larger dragonfly nymphs, terrorize the underwater environment.

Like Callibaetis patterns, damselfly imitations can be fished from the spring through the fall, with success usually coming in, around, and over weed beds. Damselfly nymphs undergo a series of molts, increasing in size as the season progresses. The mature nymphs move toward shore, where they crawl out on some convenient rock or vegetation and go through a final metamorphosis into an adult that can fly away to hunt airborne insects such as midges or mayflies. They hatch throughout the season, but when favorable conditions occur, prolific migrations draw great concentrations of feeding trout, bass, and sunfish, as well as predatory birds that tell us of the insect’s presence. Likewise, sometimes the presence of airborne damselflies over lake or stream signals that hatches of smaller insects are happening. Like birds, they can serve as an indicator that will key you into an angling opportunity.

When damselfly nymphs appear on your shirt, face, leg, float tube, or boat, something is up. Once, I was wading off the beach at Manzanita Lake in Lassen Park, casting to difficult fish that were cruising for damselflies just out of my range. I was alone and very still in the water when I felt a heavy bump against my waders. It spooked me a bit, then it happened several times, and as I turned and twisted, I saw a huge trout banging against my legs. The fish was taking damselfly nymphs that were using me as their migratory path to the surface. I remembered a thin plank on the beach, retrieved it, waded out as far as possible and stuck the piece of wood vertically into the bottom muck. I cast my Mercer’s Poxyback Callibaetis Nymph so it could tumble vertically down the plank and was able to take several fish that way.

Damselfly adults, particularly those crawling on brush or dipping near shoreline cover can attract trout or bass, and a floating pattern can do quite well. On a trip to fish Chilean lagos, our guides handed us boxes of large, blue-bodied, deerhair-winged adult damselfly patterns. We went through many flies as toothy brown trout took a fancy to fly-rod bugs cast to shoreline cover.

Tackle and Tactics

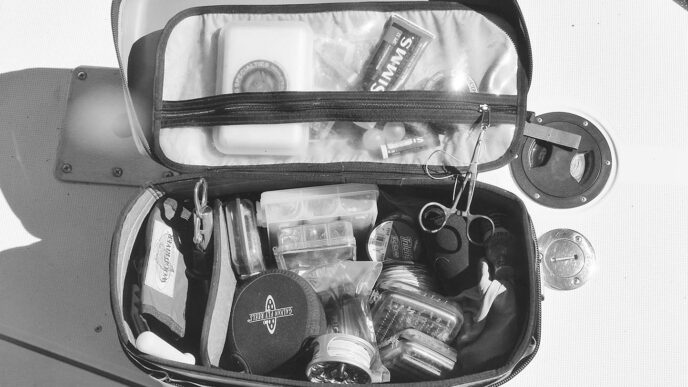

To be ready for the simultaneous emergence of Callibaetis mayflies and damselflies and to be prepared to fish all stages of their emergence, I usually carry a 5-weight rod rigged with a floating line, a second one rigged with a camo sink-tip line for presentations just under the surface, and another with a clear intermediate “slime line” for fishing intermediate depths. When simultaneous emergences are going on, it makes sense to fish an imitation of each bug simultaneously, too. Last year at Davis Lake, I used a combination setup that consisted of a small, light olive marabou damsel on a 9-foot 3X leader that was trailed 18 inches off the hook shank with a Phil Fisher UV dub Callibaetis nymph on 4X. If I sense that fish prefer one fly over another, I switch to a single pattern on a 3X or 4X fluorocarbon tippet. I use fluorocarbon because it will sink faster, and there is something to be said for its claimed lower visibility.

A floating line and a long leader allows a diagonal, but fairly vertical path for the fly, and fish of many species key on nymphs that rise vertically. Let the nymph sink, and when you start the retrieve, the nymph will rise. Pause often to allow the nymph to fall back. Most takes are going to come on the pauses. A sink-tip camo line can achieve a similar effect. A full clear intermediate line moves your fly in a horizontal fashion during most of the retrieve. One of the best all-around stillwater flies, one that imitates both damselfly and Callibaetis nymphs, is Denny Rickards’s Stillwater Nymph, tied with a light and medium olive marabou overwing and medium brown underhackle on a size 14 Tiemco 200R hook. It is available commercially, although I prefer to tie the version taught to me by Jay Fair. However, I and others with whom I fish have found that a number of different Callibaetis and damselfly patterns should be carried. What works on one lake may not do so on another. Callibaetis nymphs range from gray to tan and on into light green or sage. The classic imitation is a Hare’s Ear Nymph or A.P. Muskrat Gray Nymph. More refined and very effective patterns include the Mercer Poxyback Callibaetis Nymph, Rene Harrop’s magnificent ties, and the Phil Fisher UV-dub patterns in gray-purple. Most Callibaetis emerger patterns are generic, and the best ones are created by individual fly tyers who customize their flies. The Parachute Adams, size 16 or 18, is the classic dun pattern. I tie Ralph Cutter’s Martis Midge Emerger in Callibaetis colors, and it seems to be effective at times. Mike Mercer has a poxy back cripple tied in the Quigley style. I like an Organza Spinner for my down-wing imitations. It has the spinner’s characteristic sheen in the wings. Another choice is a Partridge Spinner, which gives a speckled effect to the wings.

Many store-bought damselfly nymph patterns are too long and too bulky. Smaller generic marabou damsel patterns are among the best. I like them tied on Tiemco 2499 wide-gape, short-shank hooks, with or without weight or a bead head, as in guide Jon Baiocchi’s patterns. On the 2499s, a size 16 fly has a size 14 gape. Other favorites are Pheasant Tail Damsels and Andy Burk’s damselfly imitations. Effective colors can include light coral, light charcoal, orange, and shades of tobacco and olive. Dave Hayashi ran the Grizzly Country Store at Lake Davis before the first pike eradication attempt. He made an ordering mistake and three or four gross of a hideous red and flashy green, tinsel ribbed, nonrefundable damsel imitations arrived from his fly supplier in Africa. These flies were the hot pattern that year. So much for our theories.

If you’re not fishing a two-bug nymph rig with both Callibaetis and damselfly imitations, you need to use different retrieves for each fly. Both nymphs move slowly, but the big difference is that the Callibaetis nymphs swim toward the surface in a vertical movement that is characterized by repetitive spurt-spurt-spurt, then a falling back. Consequently, a patient, slow, short two-to-four-inch repetitive retrieve with pauses using a floating line is best. Often takes will be on the pauses and the fall, when the nymph sinks back toward the bottom.

If you see classic head-and-tail rises, it’s a good bet that the fish are on emerging Callibaetis nymphs, stillborns, or cripples. Try to discern the feeding rhythm of your target and lead it so that your fish will open its mouth right where you placed your fly. Stillwater fish get to look a long time at your imitation. If they are on nymphs just below the surface, imparting a little movement is good. Cripples move very little, and larger fish don’t usually take moving duns. Long, supple leaders and accurate casts help.

However, damselfly nymphs swim toward shore in an emergence with a unique sinusoidal movement that is akin to that of a sidewinder rattlesnake. It is difficult, if not impossible, to imitate perfectly. I’ve tried little acrylic lips on my flies, but they don’t work well at all. A Loop Knot helps in imitating the side-to-side motion, but isn’t a strong knot when you’re using lighter tippets. With it, the nymph will squirt to the side a bit on your pauses. Another trick is to put your nymph several feet below a small pinch-on indicator that is the size of an aspirin and let wave action animate your fly. Mix small, slow strips with occasional pauses. Trout become voracious during a heavy damselfly migration and may smash the fly, throwing water in all directions and unnerving the most experienced angler. Some say that it is best to retrieve damselfly nymphs toward shore.

Most damselfly adult patterns are generic. I like smaller imitations with deer hair wings, because they don’t flutter when cast. Cast to brush and cover. Let the fly rest, then twitch it like a bass bug.

Stillwater phenomena intrigue me as few things do. I’ve been at the stillwater game for forty or so years and am still fascinated and always learning. I’ve got my dates down for late spring and early summer.