Spring Creeks: all the way back to the chalk streams of England and the writings of Frederic Halford and G. E. M. Skues, they have defined the challenges of technical angling for the sport of fly fishing. In the United States, anglers journey far and spend big money to fish the famous spring creeks of Montana, but California can boast four major spring creeks of its own.

Most California fly fishers probably can name three of them — Hat Creek, the Fall River, and Hot Creek — but they might be stumped for the name of the fourth: Yellow Creek. Like Hat Creek, Yellow Creek has had its ups and downs as a fishery, and it never has gotten the publicity that the other California spring creeks have had. However, there are good reasons to be hopeful about its future and good reasons to visit it today.

Spring creeks receive the majority of their flows from sources deep underground.

They’re all potentially fine fisheries, because these springs flow at a consistent year-round temperature and provide perfect growing conditions for aquatic insects and, as a happy mutual benefit, wild trout.

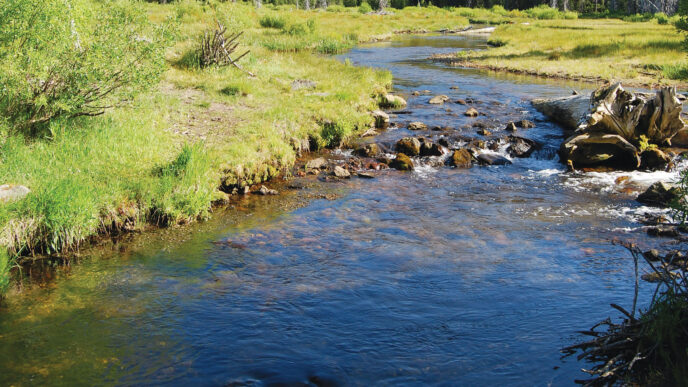

Yellow Creek starts as a small, snow-melt-fed feeder stream on the seven-thousand foot slopes of Eagle Rocks, several miles to the west of Lake Almanor. It flows generally eastward before turning southward to enter the expansive Humbug Valley, one of the biggest montane meadows in the Sierra Nevada. Approximately halfway down the valley on the west side, at the foot of a gentle, pine-covered slope, Big Springs bubbles up between boulders into a cress-filled pool, then that cold water flows east a couple of hundred yards to join the beginnings of Yellow Creek. Even in the summer, the spring-fed flow multiplies the size of the creek by a factor of maybe 10 at the junction, with the springs producing about 30 cubic feet per second. By comparison, the flow of Hot Creek in the eastern Sierra decreases from 30 cfs in the spring to 18 cfs in the early summer.

The Humbug Valley is itself one reason to visit Yellow Creek. It is a magnet for wildlife, though surprisingly, you don’t see deer in the meadow all that often. That might not be unconnected with the presence of at least one pack of coyotes around the valley. Your camping experience at Yellow Creek Campground can only be enhanced by the wailing and yapping of these wolf relatives at dusk, as they call and respond to each other over several miles. Abundant ground squirrels feed a variety of raptors, and the birdlife here is incredibly diverse. Where else might you see, on the same day, a Western bluebird perched on a fence wire and a sharp-shinned hawk hunting low over the meadow? The grasses in the valley seem little changed since the white man came. Native perennial bunchgrasses cover much of the valley, not the introduced European annual grasses that cause the overwhelmingly brown look of summer hillsides at lower elevations. On the east side of the valley, just south of where you turn off Humbug Road to the campground, is a natural soda spring that provides a source of fabulous-tasting, naturally carbonated soda water.

The Humbug Valley has seen human habitation for many centuries. It was at least a summer home to the Mountain Maidu people, and grinding rocks where the Maidu ground acorns into meal can be found throughout the valley. The Maidu cautiously moved aside when the first whites settled in the valley in 1850, but they returned some years later, because the white settlers offered them a source of work and trade goods. With the land in private ownership, cattle were grazed, and a sawmill was built, followed by hotels in 1858 and 1860, both of which burned to the ground fairly soon afterward.

Cattle were grazed continuously there up until the late 1990s. Today, the majority of the valley belongs to the Pacific Gas and Electric Company, as it has for many years, but is to be transferred to other ownership as part of the utility’s bankruptcy settlement.

From the 1970s to the 2000s: Yellow Creek Restored

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Forest Service, and California Trout have collaborated with PG&E on resource management in this valley for decades, particularly on the restoration and protection of the creek. In the 1970s, Yellow Creek was a poor fishery, a result of the long-term effect of cattle grazing on the meadow. The creek was wide and shallow, with little bankside cover, so it contained only a sparse population of mostly small brown trout. The first split-rail fence to exclude the cattle was installed in 1978, followed by a much more extensive fence-building and habitat-restoration project in 1984 and 1985, accomplished with a lot of volunteer labor from the Chico Area Fly Fishers club. Beginning in the late 1980s, catching large brown trout there became quite possible, because the increased cover and abundant weed beds now provided both food and shelter, and the relatively few trout grew quickly to trophy sizes.

But then the trout population exploded, and by the time I first fished it, in 1991, it was full of average-sized brown trout. I found the creek hard to read and fish, too. If you could approach closely enough to see the fish, which was something I was very used to doing on the chalk streams of England, Yellow Creek trout would always immediately bolt for cover. It didn’t matter how stealthily I believed I’d crept up on them and how well I thought my silhouette was masked by the willows I’d tried to place behind me — they were always on edge.

The extreme spookiness of Yellow Creek trout is a common thread in any writing you find about the creek online and in fly-club newsletters. The solution became plain to me a few years later, when I fished the stream with Chris Lee, a really fine fly fisher from England. Instead of trying to approach the fish, just wait until they approach you. Despite the two miles or more of stream he could have fished, Chris hardly moved from one short reach. He waited at one pool and watched it carefully until a large trout swam by, prospecting for food, then tied on a small nymph and caught that 17-inch brown. He followed that up with plenty of medium-sized browns from one 50-yard stretch during the evening rise.

I grew to enjoy annual visits to Yellow Creek in the 1990s, and by refining my stealth tactic, moving really slowly and keeping low, began to succeed in catching sizeable browns. The best strategy seemed to be prospecting faster runs close to the bank, where a weed bed provided cover and the flow had undercut the bank. In those protective lies, the trout must have felt safe, and their food was of course concentrated. But the broken surface of the water also provided some cover to the angler, masking a silhouette that might otherwise have been obvious against the sky. One September I finally caught a 14-inch brown trout during a Baetis hatch.

And then I discovered late fall fishing, from mid-October on. By then, the creek was usually deserted — low nighttime temperatures may be a factor. Humbug Valley seems to be a frost pocket of sorts, and it’s also at a higher elevation than you might think, at 4,300 feet, so frigid nights and even early snow can discourage anglers. Also, most fly anglers haunt the storied fall fisheries of the McCloud, upper Sacramento, Pit, and Fall Rivers by October, so a little stream like Yellow Creek often gets forgotten. The campground was always closed at the end of September anyway. And fly fishers who’d come in September had seen the Baetis hatch wane and assumed the hatch season was done, too. But no — I found good hatches and spinner falls of a larger (well at least a size 16) olive mayfly. It had three tails, so I’m assuming it was an Ephemerella, or true Blue-Winged Olive. And when the bankside grasses and flowering plants died down, it was easier to manage a fly line from a kneeling position and even possible to wade some sections carefully, both to keep a low silhouette and to have viable space for a back cast between willows on either bank. I was picking up one or two large trout during the warm hours, when the sun was reasonably high — real banker’s hours, from a little before noon to perhaps four P.M.

The 2000s: The Fishery Crashes

In the 2000s, though, the weed beds unaccountably vanished from the first half mile or so above the campground. This was the area I knew like the back of my suntanned casting hand. I had trouble locating larger trout, and as fly fishers do from time to time, I moved on to other waters. This must have been around the time when others visited the stream for the first time and talked about the tough, poor fishing. How were they to know that they were looking at trout holding conditions as poor as prevailed before the restoration? And with online bulletin boards revolutionizing the way that fly anglers communicate, the story was out: Yellow Creek’s fishery had crashed. Folks visited and caught nothing over seven inches. A correspondent writing to the Chico Area Fly Fishers newsletter was told by the campground host in August 2011 that there were no trout in the meadow, and few in the canyon below. He and a friend caught just one good trout in six hours. (Not that the last week of August under a midday sun would be my first choice for a visit, but still. ) What had happened?

I returned there in the summer of 2010. The fishing was a little slow, and I found it tough to get my beginning angler friend Felix into a sizeable trout. The weeds were still mostly absent from that long stretch, and the trout population did seem sparse. But to me, that seemed like an opportunity for the trout that were there to grab the prime lies when the weeds returned and to grow like gangbusters. Felix and I went down into the canyon below and found only tiny trout until we saw something truly huge: an otter’s head broke the surface, then another, then another. It was magical, watching this family playing and hunting. Going back up to the bottom end of the meadow, we saw a second family of four otters, also heading down into the canyon. Add two families of otters to a mysterious weed dieoff that had deprived trout of cover in the most obvious stretch to fish, right upstream from the campground, and you have a pretty good recipe for poor fishing. However, I just went back, last October, and here’s what I know, hot off the presses. There were fewer trout than at peak levels, but the weed beds were back. The hatches were mayflies, as I remembered, the trout ate them better than ever, and I had one good day, followed by one real red-letter day, when I caught browns of 12 inches or more from many of the runs. The first day, I even caught my first rainbow trout from the meadow in at least 10 years, and at 11 inches, it was the largest rainbow I ever caught there. I also spent some time trying to persuade a couple of truly large brown trout to eat a Pheasant Tail Nymph. Up where a small feeder flows in from the east, the stream is deep and narrow, and that’s a good area to occasionally find large trout out in the open. But they ignored my nymph that day, and inevitably, both of them spooked fairly quickly.

Cannibal Trout

There’s a reason for the large trout ignoring bugs and their imitations. They eat their own children. In the fall of 2007, back when the weeds were gone, I stood on the west bank, watching a large brown trout I’d spotted in the middle of a clear, gravel-bottomed run, as my buddy Luong Tam came up the east bank. It was a big fish, but what held our attention most of all was the somewhat smaller trout that the big fish had clamped sideways in its jaws. After an hour’s observation and attempted photography, we compared notes. The big fish was 21 inches long, we agreed, and the trout in its jaws, also a brown, we thought was at least 10, probably 11 inches long. The sideways hold the big trout had on this fish must have been designed to make it hard for the smaller fish to open his gills against the press of the current, so it would eventually die from the effort and could be swallowed.

But was that just a fluke? No, for I and many others have had small fish on the end of our lines charged by larger trout with aggressive intent. I believe that these larger browns become piscivorous when they reach about 16 inches. There aren’t just juvenile brown trout to eat in Yellow Creek, either — there are brookies, too, and their populations seem to ebb and flow from 2 or 3 percent of the overall trout population to more than 10 percent. A 2008 electrofishing survey of four sections estimated an average 7,797 brown trout per mile (but that’s everything from two-inch babies on up) and 1,264 brookies, topping out at 9 inches, while the largest brown was 20 inches long. Rainbows were estimated at over 70 per mile, but I know that’s totally skewed by two sections down toward the canyon, the only place they found any. I can recall catching only two rainbows in the meadow in 20 years. Brookies are throughout the meadow, for I know I caught one roughly 7-inch brookie for every three or four browns last October. And you know what we call those little brookies? Brown Trout Chow.

So you would think that streamer fishing would work for big trout. It might, and indeed, fishing guide Lincoln Gray has caught a few big browns using a rusty orange leech pattern. “It was back in the 1980s, though,” he says, “and it hasn’t worked so well recently. I used a sink-tip line get the fly down deeper into the undercuts and the deep holes by the willow roots, then let it swing out and across.” But he still goes back for the Green Drake hatch.

My choice, too, is to concentrate on the insect hatches and the larger insect-eating trout. For me, 10-to-14-inch trout are the perfect size almost anywhere, but particularly on an intimate stream such as Yellow Creek. They seem perfectly sized for the stream, hanging next to weeds, sipping mayflies, slinking away at the hint of a shadow. They’re a joy to stalk, hook, and fight — and I do mean fight. You may not get a 50-yard run, but there’ll be a golden shape hanging in the air at least once, streaming sparkling jewels of water before plunging back, only to dig under the roots of a weed bed. You’ll get a sleeve wet for sure, working a trout free of those weeds.

Hatches and How to Fish Them

If, like me, you concentrate on fishing the insect hatches, the fishing starts in June, because the creek is often high and cold from snowmelt in May (though not in drought years with minimal snowpacks). A size 16 Pale Morning Dun hatch peaks in mid-June and starts the good dryfly fishing. Soon the PMDs are followed by Green Drakes, size 8 or 10. This rather sparse hatch can be frustrating, since most of the trout will turn their noses up at a dry fly. Emerger patterns or cripples are probably the way to go during the Green Drake hatch, or at least that has been my limited experience.

July and warm evenings bring a lot of different mayflies and the best caddis hatches of the season. For the last hour of light, every fish can go crazy for caddises, but that does not make the fishing easy. Little Yellow Stones start to work sometimes, too, late in the morning and early in the evening.

August can bring the doldrums, except there are grasshoppers in the meadow, though determined fishing with them has made catching 12-inch trout harder than usual for me. Ants and beetles are the way to go in August and also the preferred way to prospect the stream all summer long when nothing is hatching.

September brings the best of the Baetis hatches that have been coming off at times throughout much of the season. This hatch is mostly a midday affair, but can last into the evening, when rusty spinners fished on the surface can be important, too. The Green Drakes will return, as well, in early September.

October brings hatches of true BlueWinged Olives in size 16, plus some Mahogany Duns the same size, their spinners on calm warm days, as well as the last of the Baetis hatches and a few more minor mayfly hatches. You will see a very few October Caddises, and I’ve yet to rise a decent-sized trout to an imitation of one.

As for November, well, I went once, just to say I’d done it, right at the end of the season. I have never been so cold in a tent. And bear in mind that it was 22 degrees one morning when I went the middle of last October. But there are still hatches in November at midday, the tiniest gray mayflies I’ve ever seen, plus a “larger” gray mayfly, a whopping size 22, with a pretty chestnut thorax. The trout seemed to like those.

As for nymph fishing, it is feasible to sneak up on fish you can see in the water and take them on a small, slim, weighted nymph. Sawyer’s Pheasant Tail is excellent for this. But you can forget the idea of putting anything but tiny split shot on the leader, and you can certainly forget indicators, because the trout will spook and run a mile if one of those hits the water.

The Future of the Valley and the Restoration of the Upper Creek

Yellow Creek has gone through many changes in the last 20 years, first the fencing out of the cattle, followed by the installation of root wads and bank structures. The complete removal of the cattle followed, which meant that the split-rail fence could come down, and now fly fishers can keep farther away from the creek to avoid spooking trout. Most recently, a new restoration project has tackled the upper creek, above the junction with the spring. Using a method called “pond and plug,” the creek channel has been remade to run closer to the natural level of the meadow, which should raise the water table throughout this huge valley and can’t help but improve the fishery in this smaller, but still interesting reach of the stream.

As for the creek’s future, PG&E’s postbankruptcy divestment is ongoing, and a stewardship council meets regularly. The Maidu tribe petitioned to manage the land in traditional ways, while California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife wanted it to be designated a Wildlife Area with the aim of preserving the fishery for wild brown trout. But the Maidu had supporters in their bid, including the Forest Service, so eventually the DFW withdrew its proposal. Curtis Knight of California Trout, which has input into the decision-making process through the Hydropower Reform Coalition, tells me the land will be transferred to the specially-created Maidu Summit Consortium, which will manage it and safeguard cultural sites. The formal transfer of title won’t happen for at least two years.

This transfer, however, might change the fishery. The Maidu have proposed removing the stream’s nonnative brown and brook trout and restoring the native rainbow trout. But there is one black cloud lingering: whirling disease. This disease was believed to be present in Yellow Creek back in the 1990s, and its presence was recently confirmed. John Hanson and Bill Somer, wild-trout biologists for the DFW North Central Region, both described it as prevalent in Yellow Creek and indeed in some parts of the North Fork of the Feather River. Myxobolus cerebralis, the parasite that causes whirling disease, has become widely established in California since its initial discovery in Monterey County in 1965. Most significant is the occurrence of the parasite in the blue-ribbon trout waters of the Owens in the eastern Sierra, but it’s in the Truckee, too. Yellow Creek’s meadow stretch has patches of silt in the composition of its streambed, and the tubificid worms that are an intermediate host for the parasite live in that silt. In addition, the ponds that have been created in the restoration of the upper stream will presumably fill with silt and provide a fertile habitat for the worms, so the DFW has taken baseline samples and will be monitoring these ponds carefully.

Brown trout are hardly affected by the parasite, and brook trout only slightly, which may well explain the species composition of the trout in the meadow. But the native rainbows, if we can even call them native after decades of planting down on the North Fork of the Feather, are definitely affected. The Maidu have mentioned using a whirling-disease-resistant strain, but Roger Bloom of the DFW’s Wild Trout Program told me that eliminating the brown trout would not be easy, and that there is not yet a self-sustaining disease-resistant strain of rainbows, either. Implementation of the Maidu’s preference will likely require years of discussions and negotiations.

The DFW asks that if you fish Yellow Creek, please take whirling disease precautions, and luckily these are not as onerous as New Zealand mud snail precautions. It is quite sufficient to dry your waders and boots thoroughly after a trip to Yellow Creek before stepping into another stream or lake. In the sun, a few hours will do it, but please undo the laces on the boots completely to facilitate drying.

The Future as the Past

With the recovery of Yellow Creek and the promise of ongoing restoration efforts, I live in sweet anticipation of the day when I will find a really big trout, 16 inches or longer, feeding at the surface of Yellow Creek on mayflies, and catch him on a dry fly. One fall, back in the late 1990s, was the only time I ever found such a fish feeding on top. But the prospect of encountering such a fish again is just one of the things that keeps me coming back to the Humbug Valley.

If You

There are many ways to get you to Yellow Creek, but here’s what I consider the simplest and fastest way if you’re traveling north on Interstate 5, California’s primary transportation artery. When you reach Red Bluff, take Exit 649 for central Red Bluff and Highway 36. Turn right onto Highway 36, Antelope Boulevard, drive through Red Bluff for 2 miles, then continue left on Highway 36. Continue up into the mountains toward Chester, passing over the headwaters of Mill Creek, then the North Fork of Battle Creek. After 66 miles, just before Chester, turn right onto Highway 89, heading south. After 4.5 miles, take a right turn onto Humbug/Humboldt Road. After half a mile, turn right onto Humboldt Road, signposted to Humbug Valley. This logging road is very well-graded gravel and is passable in any vehicle as long as you slow for the washboarded bits. After 3.7 miles, you will drop down into a meadow and cross tiny Soldier Creek. Just beyond that, turn left at the crossroads and cross over Butte Creek, then keep right as the road rises gently alongside Butte Creek.

The only tricky junction is at almost two miles on this road, where you need to bear left. There should be a sign saying “Humbug Valley.” Take that road for 3.6 miles to another crossroads, where you turn left and drop down into the valley. Cross the valley and take the first right, signposted to Yellow Creek Campground. It’s 1.5 miles to the campground, or you can park on the side of the dirt road anywhere before it and walk across the meadow.

It’s also possible to reach Yellow Creek by coming up Highway 89 from the south, if you’re coming from, say Truckee. MapQuest will also suggest both Highway 32 from Chico and Highway 70 up the North Fork of the Feather River. I’m sure both are slower, and in the case of the dirt roads from Highway 70 through Caribou, also an easy way to get totally lost.

—Stephen Rider-Haggard