The first time somebody gave me a fly while singing the praises of an attendant ultraviolet material, I placed the fly in a box and, like any right-thinking steelheader, forgot all about it. Later, on a day when it seemed nearly every fish had left the river, if not also the entire state, I dug through my box, rediscovered the fly, and, reasonable guy that I am, decided I would give it try. No surprise to me, the fly failed completely. Worse, on even my longest casts, the alleged UV material woven into the wing could be seen radiating flashes of vibrant blue with the same Las Vegas light-show intensity now popular with highway patrolmen and their strobescent steeds, a kind of rock-and-roll laserfest that surely sent the very last steelhead, be it buck or hen, bolting for distant cover.

Today, with most of us a little more savvy about UV materials, I’m certain that it was some sort of ultraviolet fluorescent material that caused my steelhead fly to glow as though a dollop of radioactive waste was swinging on the end of my line. Clearly, I wasn’t sold, not any more than the fish were — at least not on a lazy, low water afternoon, a day designed for waking a sparse little Muddler, a tactic that had failed earlier to stimulate a single rise. Having never had much faith in flash or bright colors in the first place, I accepted this brief UV experiment as a momentary lapse in judgment, yet another instance of believing in the possibility of a miracle fly, one that might spin the odds my way.

Which is pretty much the UV buzz today. Only now, we’re privy to a host of new and allegedly scientific explanations for why we need UV this and UV that, a line of reasoning that makes you wonder how any of us ever caught a fish in the past. It’s hard not to sound skeptical. And lately, the naysayers have posted some fairly harsh criticisms, weighing in with published findings supported by genuine research, the kind of heady data that will quiet a room full of fly fishers quicker than a mention of Shakespeare. The gist of the current UV claims state that fish see a broader range of light than we do, and since insects and other prey have a number of reasons for reflecting ultraviolet light, we should incorporate fly-tying materials that do the same. Critics, however, contend that many of the fly-tying feathers we traditionally use already have UV reflective properties. More significantly, the scientific literature suggests that once trout get past the fingerling stage, they actually don’t have the optical mechanisms mentioned so frequently since Reed Curry sparked interest in UV materials with publication of his book The New Scientific Angling.

Who do you believe?

I must confess, I’m reluctant to probe the debate too deeply. The whole notion of “scientific angling” smacks of something contrary to my own aims as a fly fisher. If I thought that fish could be sighted, stalked, and fooled by methods gleaned from data gathered in a laboratory, I would have given up the sport long ago and retreated to the monastery with my begging bowl and deck of tarot cards. Like gardening, poetry, and love — to name but a few of my other favorites — fishing remains interesting to me this late in life because it can’t be reduced to a science. Formulas and recipes are at best suggestions for where to begin. The adventure starts when you run out of answers, when the map you hold ends at the edge of wilderness.

There’s also the notion that we see only what we believe in the first place. Even the scientists come up against this one. If I believe stars travel through the sky, that’s what I’ll see as I follow the course of Orion’s Belt on a sleepless night. If I believe the Buttercup Bruise is effective because the angle of its wing mimics the cant of the wings of the emergent Pale Evening Dun, I’ll refuse to fish the flies I tied with wings that didn’t turn out just right — and the flies I use that work will prove again how important it is to get those wings cocked precisely so.

Still, we owe a lot to those willing to take the empirical “data” that most of us gather throughout our careers and elucidate it with genuine science. If, after all these years, it turns out that peacock herl is such an effective tying material because of its UV-reflective properties, not just because it’s “good shit,” we might devise even more reasons to weave it into our favorite patterns.

But the question remains on the table and, for some of us, fuel for debate: Should ultraviolet properties now be considered a significant element of fly design and fly tying materials? Do we add the UV component to the short list of other essentials — size, profile, color, movement — that we’ve traditionally attended to in patterns we’ve fished and tied in the past?

Faced with these and other UV questions, I invited Curtis Fry to swing by and pay us a visit at The Roost. Curtis has posted a few blog entries and videos about tying with UV materials; he belongs to that new niche of tyers who have created an online presence that allows them to tie flies for an audience and generate support from companies that sell the materials that go into their designs. This is pretty much the business model that Gary LaFontaine developed thirty years ago; the main difference is that Gary relied on books and magazines, as well as sportsmen’s shows and other personal appearances, to share his innovative patterns — and of course, he also sold the materials needed to tie the flies he invented.

The good news for modern tyers — and even old farts such as me — is that today, we actually get to watch skilled tyers like Curtis Fry simply by clicking a link to a Web site. Like tyers from any era, Curtis owns the usual assortment of theories, speculations, and prejudices. He’s also a heck of a tyer, creating lovely patterns that you’re absolutely certain will catch fish, if only because they look so much better than anything you produce — and your patterns don’t do so badly already, thank you. What Fry and his ilk are really demonstrating, of course, is that you, too, can create handsome, effective flies, and since pretty much everybody agrees that tying flies only enriches the pleasure we derive from the sport, we should be grateful somebody’s taking the time to show us how it’s done.

But what’s his take on the UV buzz? Is there something here we all need to know? Thankfully, Curtis is enough of a gentleman — and an angler — that he refuses to make any far-reaching claims. He’s interested in this notion of ultraviolet reflectance or reflectiveness or reflectivity, whatever the case may be, and he’s taken to employing UVR (ultraviolet reflective) materials in some of his patterns. But for every time he suggests that these are concepts applicable to flies and fly fishing, he adds something more that reveals his own uncertainty about whether UVR is the game changer others make it out to be.

The most he’s willing to say is maybe. A strong maybe, yes, but maybe nonetheless. Or in Fry’s own words, “There’s some pretty compelling evidence that it might actually make a difference.”

That’s a fairly soft endorsement — and this from a guy who could be motivated to pitch these products for personal gain. Like most of us, Fry knows it doesn’t really matter what anybody says about ultraviolet reflectivity and UVR tying materials. The fish will let us know if we’re on the right track.

Which is where Fry’s own soft-hackled drake pattern, the Mailman, enters the story. First off, you have to like the name. And I enjoy few things more than seeing traditional designs hold their own despite the hype and hoorah of the next best thing. Of course, I’ve made it no secret I’m a sucker for soft hackles.

Because so are trout.

Whether the Mailman delivers because of its UVR materials or in spite of them — or maybe even because you’ve actually happened upon a hatch of Green Drakes, perhaps the most intoxicating hatch of all for trout and anglers alike — I doubt science will ever provide the definitive answer. Really: Is there any reason anybody anywhere should be getting paid to perform this kind of research? In the face of all that ails the planet and the last of the wild rivers in which trout swim?

It’s only a game, friends. If you think ultraviolet is the answer, you’re probably asking the wrong question.

Tying the Mailman

Hook: Allen D102BL, size 10

Thread: Light olive UTC Ultra thread, 70 denier

Tail: Spirit River UV2 mallard flank, dyed wood duck

Body: Pearl Mylar, coated with Clear Cure Goo Hydro

Ribbing: Pheasant tail, dyed green

Thorax: dark olive Spirit River UV2 Seal-X

Hackle: Olive Hungarian partridge

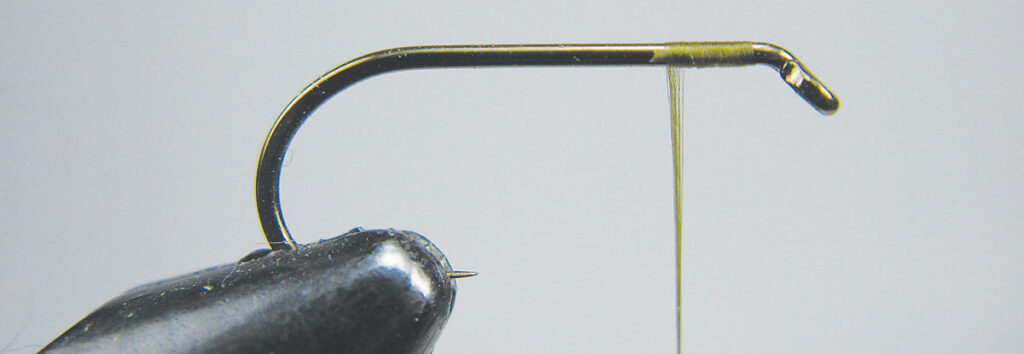

Step 1: Secure the hook in the vise and start your thread.

Step 2: Although this is Curtis Fry’s pattern, it’s a traditional soft hackle, so I suggest tying it the traditional way. Select a partridge feather with fibers about the length of the hook shank. Peel away the fuzz at the bottom of the feather. Now hold the hackle in line with the hook with the concave side toward you and peel away the fibers on the top half of the stem. Then tie the hackle stem to the top of the hook just behind the eye, the concave side still toward you.

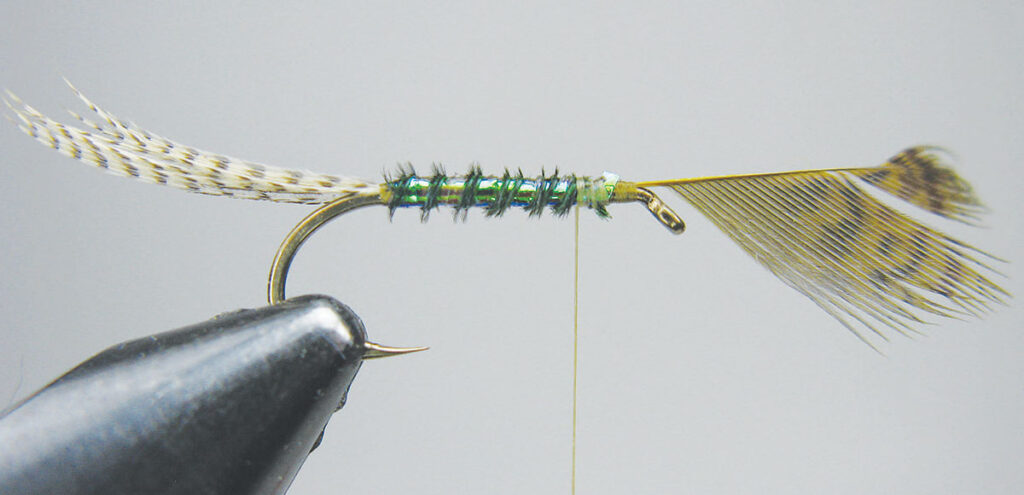

Step 3: With your thread at about the midpoint of the hook shank, tie in 8 to 10 fibers of UV-treated mallard flank. The tail should end up about the length of the hook shank.

Step 4: At the root of the tail, tie in two pheasant tail fibers.

Step 5: With your thread still at the tail, tie in a length of pearl Mylar. Advance the thread to the thorax area. Wind the Mylar forward and tie off at the thorax area.

Step 6: Before ribbing the fly, coat the Mylar with Clear Cure Goo Hydro — or head cement or lacquer, if that’s what you have. Hold the pair of pheasant tail fibers in your hackle pliers and wind directly over the wet coat on the Mylar. By the time you finish winding the rib, the coating material will already be drying, strengthening the ribbing.

Step 7: Load a pinch of dubbing to your thread and create a pronounced thorax. Your thread should still be in back of the hackle-stem tie-in point.

Step 8: Now for the hackle. Hold the tip of the feather with your hackle pliers and wind back from the hook eye. After two or three winds of hackle, take a turn of your thread and lock the hackle stem to the hook shank. Continue winding your thread forward, working it between the hackle fibers, which will prevent the feather from unraveling the first time a fish bites on it.

Step 9: You can tidy up any errant hackle fibers with a judicious turn or two of your thread. Then clip the hackle stem, create a slender head, whip finish, and dress with your favorite head cement, lacquer, or goo.