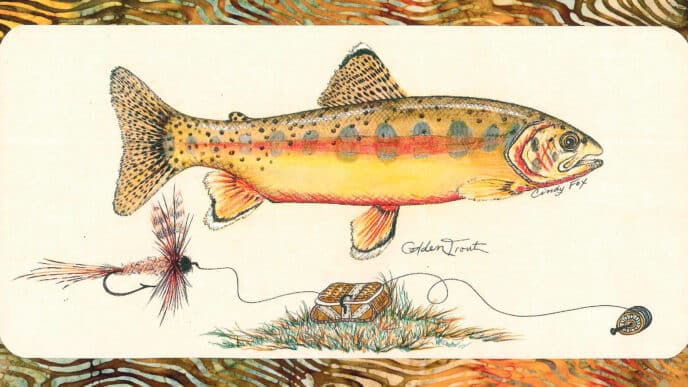

Fly Fishing is not just one thing, but many things, with many different kinds of rewards. There are anglers who love fishing for eight-inch brook trout on tiny mountain streams and anglers who cast 12-weights to exotic species such as the 200-pound arapaima of Guyana. There are steelheaders who thrive in (or at least endure) snowstorms while seeking the adrenaline highs of a grab and a screaming reel and bonefishers who live for stalking the denizens of tropical flats. Even among fly tyers, there are those who find satisfaction in serving as curators for traditional styles, such as the Catskill dry or the British spider, or who love the challenges of tying full-dress salmon flies, while others take to scuba gear to observe in their own environment the behavior of the naturals they then try to imitate and yet others who just want to tie a few flies and go fishin’. Among all the different types of fly tyers, the tyers of realistic flies stand out for the astonishing verisimilitude of their creations, and among tyers of realistic flies, none stands higher than Southern California’s Bill Blackstone. We wanted to know more about what he does and why he does it.

Bud: I’ve read that although you were born in Illinois, your family moved to Southern California when you were young and that it was there that you started fly fishing — in the Ventura and Santa Clara Rivers and Sespe Creek — and started tying flies. Ventura County is not often though of as the cradle of fly fishers in the West. What was angling like there when you were a kid, and what drew you to fishing with a fly?

Bill: If you look at rainfall in Southern California in the 1930s and 1940s, you will see that there has been a drastic change. There was water year-round in almost all the rivers and creeks when I was young — the Ventura River on the north side of town and the Santa Clara River to the south, three and a half miles. Both ran clear after the first winter storms — open to the sea. Both contained steelhead, which ran from December to March. Trout were planted in almost every stream in the area, so essentially, there was year-round fishing. When we were not fishing for steelhead, it was for trout or halibut or perch or jack smelt or sea trout. Jack smelt of 14 to 16 inches caught on a fly rod were a thrill. We used a bucktail fly, red and white or green and yellow, and you could get into a school of them and catch as many as 25 per day. All that was within reach of a bicycle ride.

My father and his family were anglers, and my aunt was a bamboo rod restorer, so becoming a fly fisher was a natural transition. My father died when I was 10, mother worked, and I had time on my hands. My mother allowed me to hunt and fish alone as long as I kept to the approved hours of going and returning. I spent time with a neighbor who fished and hunted. He taught me knot tying, tackle care and repair, and showed me the excitement of the sport.

My aunt, who never married, was a hunting and fishing advocate. Like all equipment, bamboo rods require maintenance and repair. She could do all of this. She would strip off the old finish and windings and refurbish the rod to like-new condition. She even maintained the exact same silk colors and wrapping placements. Naturally, some of that rubbed off on me. It only added to the fishing experience. I cannot think of any part of it that still does not inspire me.

In fact, fishing and the fishing experience have sustained me throughout my entire life. There is not one part of it that turns me off — other than wading beyond my waders’ height. Tying has kept that fire burning brightly. Before I started tying, I was introduced to a person who was a prospective teacher. In our first encounter, he said, “What I am going to show you, you will have to repay.” I was a 10-year-old kid, and my parents had no money. I thought it was all over until he explained that he meant I should give back to the sport. I have worked tirelessly to keep that promise. He explained that he was giving me a gift for life.

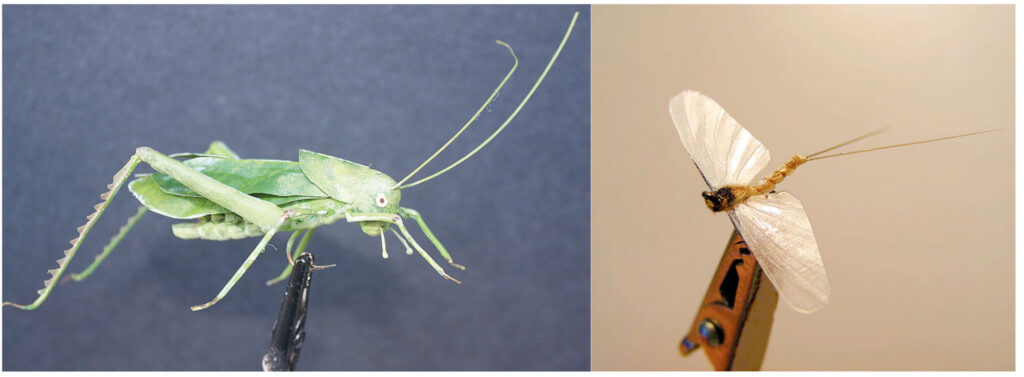

Bud: It seems like every fly tyer in the community of those who tie realistic flies has what I’d call an “origin story” — an account of the “Aha!” moment when they thought, “Ya know, I bet I could tie a fly that actually looks like that bug there, right down to the details.” But as I was preparing for this interview, it seemed as if one of the things that appeals to you about tying realistic flies is that doing so involves a whole series of “Aha!” moments as you come up with solutions to problems posed by the task of representing the insect accurately. Is there an original origin story — the first “Aha”? And what is it about tying realistic flies that keeps you at it?

Bill: My first real “Aha!” moment came while tying a black stonefly nymph. If you study nymph patterns, you see dressings all over the map, as opposed to dressings for wet and dry flies. I wanted more realism in mine, and I set out to perfect ways to achieve it. I wanted realistic legs and a skin or shell that I did not see in other patterns. Breaking the pattern of “it has to be feathers and furs” opened a whole new world.

But I first had experimented with realism as a kid. I loved taxidermy. It was the most creative activity I had ever seen, and I spent some time watching

a taxidermist actually doing it. He would give me scraps of fur for tying, and I would help him clean his shop and do odd jobs to repay him. This experience prompted me to experiment. However, I was still stuck in the feathers-and-furs mode, so nothing ever satisfied me until I decided to throw caution to the wind. I tried a new attitude: use whatever it takes to reproduce the insect, not worrying if it even would fish. If glue works better for a solution, use it. If wood achieves the answer to a problem, use it.

By this time, Rapala lures were the rage. I looked at them and their success and decided to use wood and paint, if it achieved my goal. From that, it all came together. I could make anything or copy a pattern down to the last detail. Out of curiosity, I tried them on the fish. Some worked, and some did not. I have modified them for the fish, changed the legs by going back to feathers or using rubber medical material so they move.

I wondered if my attempts were worthwhile or was this a waste of time. The people who saw my first attempts scoffed, but I decided to please myself, and I kept going. As my results got better, I expanded my thinking and my material choices. I became more satisfied. I now knew what I was doing. I may not be the best. A fly may not be fishable, may be fit only for a frame, but the beetles and stonefly patterns I was tying were as good as I could make them. No one who looks at them will deny that, and that was reward enough to keep me going.

Tying realistic flies no longer involves following a recipe and changing only hook sizes. It challenges you to think and plan and experiment in new and different ways to achieve your goal. It leads you into materials beyond your imagination and methods of working them into a satisfactory solution. It opens doors to new techniques and materials previously unused. I simply am captivated by the art of realism, of realistic fly tying.

Bud: I know tyers who refuse to use anything but natural materials, the same things available to the sainted Theodore Gordon a hundred years ago. By contrast, your approach to tying materials is totally wide open — one writer said of you that “the only material I know of that has not been utilized is duct tape,” and you continue to push the envelope whenever possible. Why did you first turn to synthetic materials?

Bill: If you think about the standard materials used in tying conventional flies, it limits you. Just look at today’s flies, with all the flash and flutter offered by the synthetic materials. They not only have opened up a wider selection, but have proved more effective. I would like to think I have had some influence on that. If it is better, use it. I have been using “other products” for almost 35 years in one way or another.

Bud: The Swedish fly tyer Ulf Hagström has said that a two-year “obsession” with tying “super realistic insect imitations” significantly improved his fly tying. You also tie more conventional flies and teach basic fly-tying classes. What kinds of crossovers are there between tying realistic flies and more conventional patterns in terms of techniques and materials and, more broadly, in terms of a tyer’s mindset?

Bill: Fly tying starts with becoming familiar with and handling materials, creating a product you think will attract a fish. What better way to start than with conventional materials? Once you are familiar with this process, I think substitutions and additions begin to sneak into your patterns. This is the start of experimentation. The next step is redesign, change, and technique innovation.

Bud: The highfalutin name for what you do in imitating an insect is “mimesis,” a term from the world of art, and one of the issues that your work as a tyer raises is to what extent tying flies is an art or a craft. Proponents of impressionism in imitating insects lean toward easily tied creations, and some say of tying a Wooly Bugger, for example, that any kid can do it, just as critics of Abstract Impressionism in painting compared it with finger painting. But you carve bodies, rough out projects on the armature of an unbent paperclip, and do a lot of things that are what a sculptor would do. Are you pursuing a craft, or making art?

Bill: There is a fine line between art and craft. Where one starts or the other takes over depends on the tyer’s imagination. The reason I use paperclips is to practice on, to develop a technique or a specific product as a solution to a design problem. I found early on that using a hook forced me to tie a complete pattern, when all I wanted to do was design a wing. If in my trials I was experimenting with several materials for that wing, why use a hook? It is just a waste. Concentrate on one solution at a time.

Bud: One argument for the answer “It’s art” to that question is that there’s a market for it that goes beyond the utilitarian use of the flies as flies. I doubt that the remuneration on a per-hour basis is much beyond that of flipping burgers, but people do seek these creations to hang on their walls, and there’s also the market for insect imitations as props in movies and TV shoots. It’s said that many flies are tied more to appeal to anglers than to fish. From everything you say about your tying, it’s clear that for you, the appeal of tying realistic flies is that you’re just flat-out having fun. Any idea what it is that appeals to those who seek out your work?

Bill: I think you are right. Good innovative creative tying is its own reward. The better the imitation, the greater the reward. If you are in it for remuneration or big rewards, though, you will be disappointed. At some point, you survive and push on by continuing to improve your product, which sometimes surpasses satisfying the fish.

Bud: Here’s the flip side of that question. Do they actually appeal to fish? I’m sure everyone asks this, but readers will want to know: Do you fish any of them? Do they catch fish? After all, your flies are the antithesis of the genre known as “guide flies” — flies meant to be quick to tie and no great loss if you hang them in a tree.

Bill: I tell all who ask me that some do catch fish, and some do not. Some scare fish. Some look great, but catch only anglers. When they do catch fish, it all comes together, and fortunately, many of the materials and techniques translate from flies that don’t work to flies that do. I tie for reasons other than fishing, though. I now live in a fishless area with a lot of time on my hands. The tying experience feeds the urgent need to keep active. If you go into tying concerned with the issue of spending too much time on your efforts, do not tie. Buy your patterns from another tyer. But you will miss a part of the fishing experience that I think is necessary for a complete satisfaction.

Bud: I seem to ask this of everyone, but the Internet has made a big difference in all aspects of fly fishing, both as a sport and as a business, and I wonder what effect it has had on the genre of realistic fly tying. I know that in the community of realistic tyers, my friend Bob Mead and the late Dave Martin used to tie together over Skype, for instance, despite being separated by a continent. But beyond making it easier for tyers of realistic flies to stay in touch, I wonder how the Internet has affected the dissemination of techniques, materials, and interest in tying realistic flies.

Bill: I have not been affected by the Internet. It is not part of my educational background. I am more than stupid in this area. When I tie at a show, I am doing just that, not observing other tyers. I work entirely on my own, without influence from others. The materials and techniques are only mine. I work alone and experiment on my own. My garage holds more experimental stuff than any hardware store. Much of it did not work, and there it sits. I tell everyone I am the most failed person on the planet. Once in a while, it all comes together, and for me, it is a rush like catching a world-record fish. It feeds that part of your being that pushes you onward.

Bud: Here we are already at the traditional Silly Tree Question: If you were a tree, what kind of a tree would you be?

Bill: I were a tree, it would be a bonsai. I would be small enough to be observed in my entirety without have to be seen from a distance. I would receive undivided attention, protection, admiration. Who could ask for more?