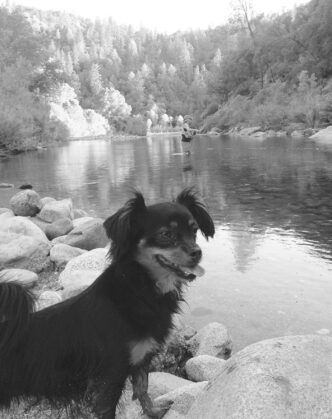

I really needed this trip. After a few years in a boring, cold corner of New England, I was back in the Golden State, dejected from looking for work for nearly two months with little to show for it. It was time to escape, reboot. Heading off to the mountains to fish and backpack with my father and brothers-in-law was exactly what I needed.

We carved out a few days from our calendars and decided we would spend most of this trip fishing from a single base camp. Decades ago, when he was about my age, my father-in-law visited a little-known corner of California, the Marble Mountain Wilderness, and after hovering over calendars and maps for a few nights, we settled on a lake there that a friend said had easy access and good fishing. Easy and good. Of course we had to choose it.

The day of departure is a tale of jump-starting a dead engine followed by long, uneventful hours on the road, bacon cheeseburgers, then too many beers in camp at the trailhead. You know, the usual. The next morning we awoke sluggish, thirsty, and excited. My guess was that we had about six and a half miles of moderate hiking ahead of us — probably about four hours.

An hour and a half after we had crossed the wilderness boundary, we met our first hikers. A pair of middle-aged men were coming down from the same lake to which we were headed. Strapped to their backs were small, light packs and spinning gear. We stopped to chat. They had been hiking downhill toward us for three hours. “Good thing you guys are young,” one of the men said. I looked at our hulking packs, filled with days’ supplies of food, adult beverages, sunscreen, bug spray, pots, pans, and all variety of hiking accoutrements.

Three hours later, we were still pushing up the endless switchbacks, twenty minutes at a time between breaks. Though not high in terms of overall elevation, these mountains were kicking us in the lungs. We broke out the map to reassure ourselves that there was not much farther to go, that we had done most of the climbing, that the switchbacks had ended, that we would soon reach our lake.

No such luck.

We climbed another hour. But finally the trail flattened, and we walked through a gorgeous mountain meadow to the lake’s shore, where we peeled off our sweat-drenched clothing and waded into the cool, crystal-clear shallows. Trout rose and jumped and splashed all around us. It had taken us more than seven hours of climbing to reach this place. And, as we lay on rocks sunning ourselves, a group of twelve teenagers came waltzing down the meadow and grabbed the primo campsite that we wanted.

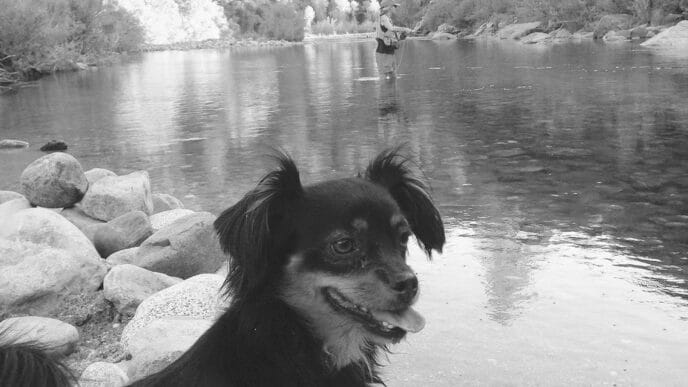

We spent the rest of the day wading and casting to rises from healthy brook trout of up to thirteen inches. The fish were feeding with abandon, catapulting clear out of the water after damselflies and dragonflies. It looked like a raceway full of hatchery fish at feeding time. That night we had a fish fry over a roaring fire with plenty of red wine, whiskey, and rum, and I slept better than I had in months.

More fishing the next day. As I waded, damselfly nymphs swam to my legs and tried to climb them. Large salamanders calmly rose to the surface to gulp air and gracefully kick-turn back down to the bottom. Bears, deer, and coyotes had left their sign along the shore in the shade and in the waist-high wildflowers and mule’s ears in the meadow. I smelled trout slime on my hands and brushed midges and mosquitoes away from my ears and nose. I could feel the distinct coolness on my bare feet and toes of small underground springs entering the shallows from under the soft mud and gravel.

Every color of the painter’s pallet was visible in the spots, vermiculations, fins, and skin of the little brook trout. Some fish were olive bodied with almost silvery pink spots, like their cousins the arctic char, while others had deep, burnt-orange bellies, crimson tones on their fins and hooked jaws with sharp teeth on top and bottom, reminiscent of a spawning sockeye salmon fighting for a mate. Brookies are by far my favorite trout.

We each kept fish for the camp and gorged on them for dinner, using the bones as toothpicks. Then we went back out for the evening rise, if there could be such a thing during a day when the trout did not stop jumping and chasing food. I stripped dry flies as though they were minnows, cast streamers into the depths. I experimented with new patterns that I couldn’t name. Savage strikes reduced my flies to a few feathers on a hook. I didn’t stop until well after the sun had dropped below the horizon.

That night, the light of a nearly full moon lit our camp, and we took the rainfly off our tent so we could soak up its glow. Coyotes yipped and howled from the ridgeline above us.

In the morning, we made it back down to the trailhead and car in just five hours, passing several hikers on the way up. They looked as completely unprepared for the journey ahead as we had been.

Sore, chafed, stiff, and exhausted, we stopped at In-N-Out on the way home, our usual ritual on fishing trips. Some things you do because you need to do them, but some things you do because that’s what you do. The thermometer read 113 in the parking lot. Back to reality.