Finding a needle in a haystack is easy . . . if you cheat and use a magnet or perhaps set the hay on fire and pluck the needle from the ashes. Trout occupy a tiny fraction of a lake and even less of a typical river. Your job is to locate that very small piece of wriggling meat in that relatively huge body of water. It’s like finding a needle in a haystack, except that draining the lake is considered bad form.

Chumming and using bait works because it draws the fish from where they might normally hide. It is the fishing version of finding the needle with a magnet. Angling with bait can be a very fun way to catch fish, but we won’t acknowledge that in this magazine.

Mindlessly trolling a lure through the water, whether behind a decked-out Boston Whaler or a lowly float tube, is another form of cheating. Trolling with a fly is no less mind-numbing, but the Kiwis have named this sport “harling” in an effort to elevate it to a social class above that of hardware draggers.

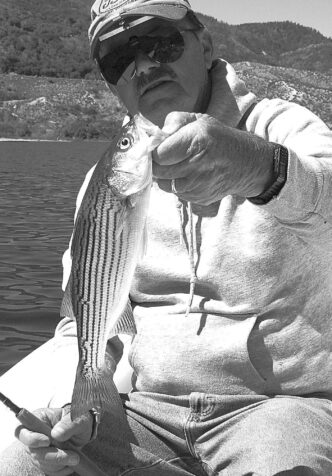

Without bait, electronics, harling, or other form of cheating, it can be exceedingly difficult to find a single fish. What isn’t nearly so difficult is finding lots of fish. Though trout aren’t schooling fish, they frequently take advantage of other species that are. An obvious example are schools of forage fish. Forage fish or baitfish (simply called “bait” by grizzled veterans) often congregate in huge masses that no self-respecting trout would ignore.

Mikey Weir targets spawning schools of tui chubs in his quest for fly catching some of the biggest trout in the state. Though the chubs themselves may be invisible, their schools displace water in a fashion that might be mistaken for a brief gust of wind. He looks for pockets of riffles that appear out of nowhere, then disappear as the school descends in the water column. Often the “push” of water will zephyr across the lake, then split or turn abruptly — a good sign that a feeding fish has appeared in their midst.

Shad are an equally important baitfish. They aren’t nearly as subtle as chubs and will frequently explode from the water like buckets of silver dollars as they evade predators. Shad are an oily fish, and frequently you can smell them before you see them. I think they smell like cucumbers, but others say they smell like shad. The oil released from shad can create an opalescent or glassy sheen that can be seen from a quarter of a mile away when the sun is low and reflecting off the water. The oil also acts as a surfactant that breaks down small riffles and waves. The result is a patch of calm on an otherwise active surface.

Shiners and minnows can create very dense schools consisting of thousands of individuals. Like chubs, their presence can be detected by “nervous” water that ripples and shakes, but more often, their huge numbers will be revealed by black or gray clouds that ghost through the water.

With any school of bait, don’t be tempted to cast into the fray, but swim your streamer along the edge or let it sink and retrieve beneath the school. Very often the largest trout (or bass) will be underneath the bait, rather than amid or along side it.

Whitefish and carp are frequently found in congregations — not technically schools. They often feed by disturbing the riverbed, then grabbing dislodged food items. The resultant clouds of silt, called muds, betray their activity. Trout exploit the work of the other fishes and are commonly found just down current of the mud, alert for any nymph, crayfish, or other invertebrate in the drift.

While trout may be stealthy, smoothscaled, and difficult to spot, whitefish are easy to see. Whitefish generally mill in pods, and their rough, faceted scales reflect light in all directions. As whitefish twist and turn to grab food, their golden flashes look for all the world like a Coors can tumbling down the riverbed.

Take a seat upstream and observe the whitefish. Among the golden semaphores you will see an occasional blink of white. These are the mouths of trout. Whitefish have small, nearly invisible pecker mouths below their snouts, while trout have white, gaping maws. Though the trout will be nearly invisible, the pod of whitefish will alert you to their presence, and the tell-tale white mouths will become the target of your drifting nymph.

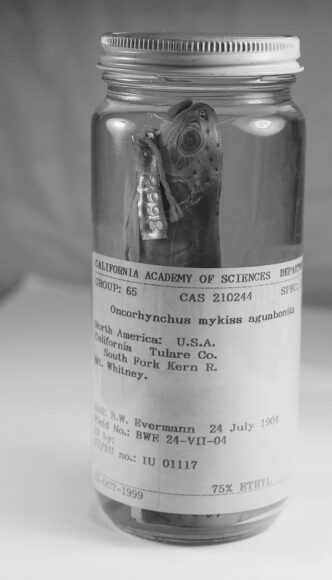

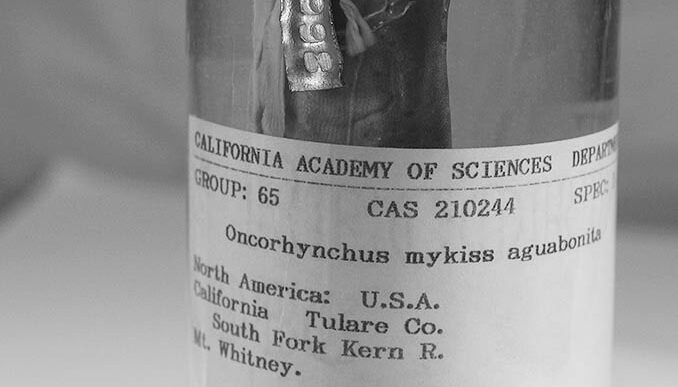

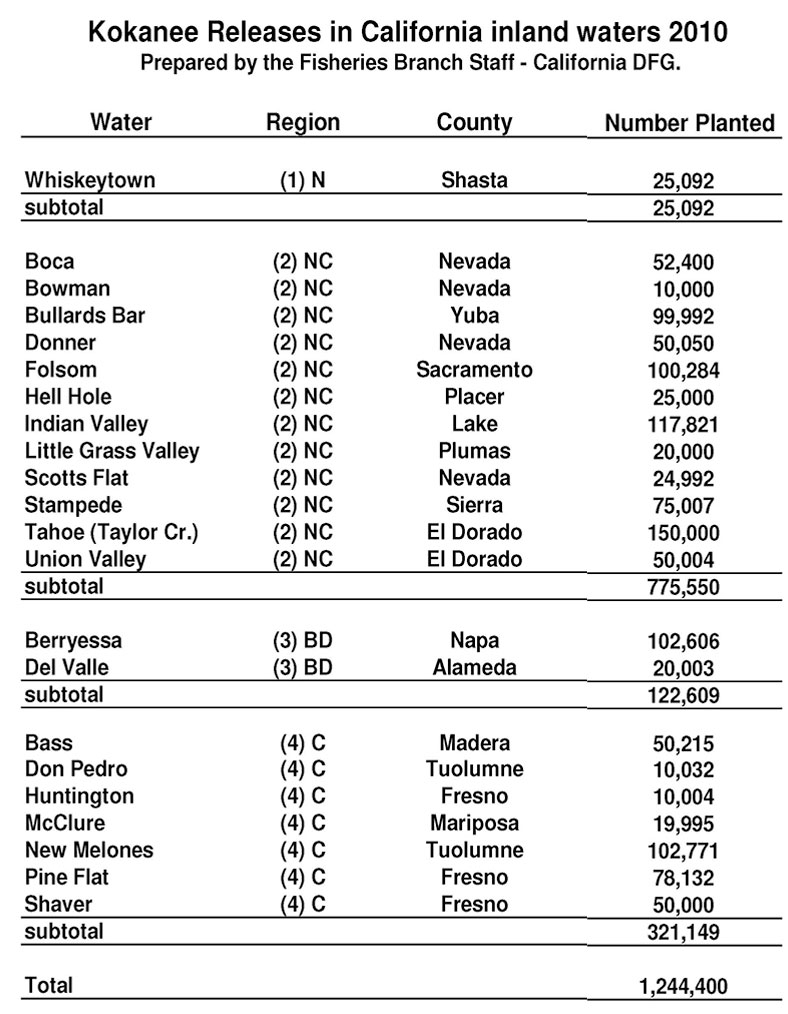

The best schools of all are those of kokanees. Kokes are landlocked sockeye salmon. Usually the schools are too deep to be of interest to flyrodders, but early in the spring, they venture into the shallows, where they provide great sport. When a school is located, a small beadhead or Birds Nest nymph twitched through the mass will usually result in a limit in short order. Kokanees are one of the few fish I don’t release. They have a short life span, don’t naturally reproduce in California waters, and taste incredible when cured in a maple syrup brine and finished in cool alder wood smoke.

Most kokanees live in lakes for three years before making their one and only spawning run. No one can give me a good reason why California kokanee populations aren’t self-sustaining, but apparently they spawn in vain. Though kokes are planted in lakes and reservoirs, they follow their anadromous instincts to find the ocean, and many smolts end up swimming over spillways or through penstocks to take up residence in rivers downstream of the lakes. In August or early September, the kokanees form large schools at the mouths of reservoir tributaries or in deep pools in rivers where they have taken up residence. As the fish quickly mature, they turn scarlet and their heads olive green. The males are much more brilliant than the females, and they develop a characteristic hooked jaw known as a kype.

Very large browns and Mackinaws take up residence under the staging masses of kokanees and pick them off at their leisure. A big red-and-green streamer would seem the obvious choice to target the trout, but to be honest, I’ve never had much success. Perhaps there are simply too many living targets for my feeble imitation to draw interest.

By mid-September, the upstream run begins. Brown trout follow the kokanees into the rivers, where they become fair targets for streamers and nymphs. The browns are masters at camouflage and hug the riverbed underneath the mass of salmon or hold tight to root wads and undercut banks. Though the browns may be impossible to see, trust that where you find schools of kokanees, browns are in the mix or close at hand.

The salmon start cutting redds and initiate spawning several weeks before the browns. Thousands of apricot-colored salmon eggs sprinkle the riverbed, and you might suspect an egg imitation would match the hatch. Unfortunately, your egg will rarely get past the kokanees. Though the kokes aren’t feeding, the bright orange-and-pink egg imitations invoke vicious grabs, and the volume of bodies the pattern has to swing through makes snagging inevitable. When hooked, these fish swim a few feet and then wallow about as you hand strip them in. After unhooking the third slimy fish, the novelty is gone (red kokanees are mushy, and the meat along the lateral line is dark and muddy tasting. Don’t bother bringing them home unless you are really hard up).

Surprisingly, the browns seem to prefer eating bugs kicked up by the nest-digging kokanees to eating the abundant roe. A dark, lightly weighted nymph is the ticket. The salmon aren’t nearly as inclined to strike at the bug as they are the brightly colored egg, and being lightly weighted, it stands much less chance of snagging than does a heavy fly or one anchored to split shot. When you start seeing browns pairing up or wriggling in the gravel, it is time to leave them alone to make babies.

Usually, by mid-December, most of the browns and kokanees have ceased spawning. Kokanee carcasses will litter the riverbed, and at this point, the post spawn browns and resident rainbows are eagerly fattening up on rotting salmon flesh. A cream or gray chunk of rabbit or marabou lashed to a size 4 streamer hook and dead drifted through deep holes or along undercuts can work magic.

Consider reading this article as your homework assignment. Now go find a school.