It is only a question of time, a very few years at most, when the golden trout of Volcano Creek will become practically exterminated unless it receives protection.”

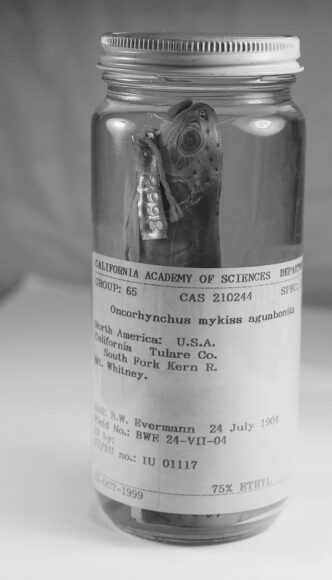

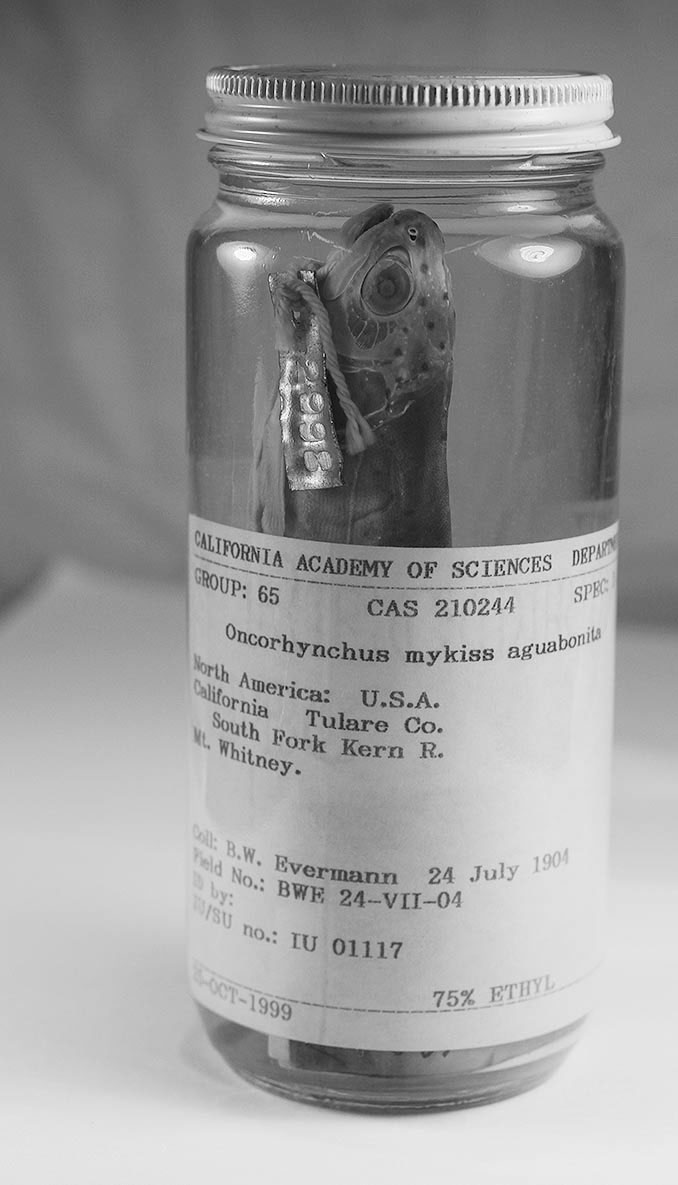

— B. W. Evermann, U.S. Bureau of Fisheries Report, 1904

California Golden Trout have a high likelihood of extinction in the next 50 to 100 years, if not sooner.

— Dr. Peter B. Moyle, SOS: California’s Native Fish Crises, 2008

So what’s with these golden trout? In a review of 140 years’ worth of literature, the recurring themes are that the golden trout is one of the world’s most spectacular freshwater fishes and that it is teetering on the brink of extinction.

At the request of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, Barton Evermann led a U.S. Bureau of Fisheries expedition into the waters of the southern Sierra to survey the status of the golden trout. The fish populated but a single watershed, and its reputation as a “wily sportster,” “bejeweled fantasy,” and tasty morsel compelled the masses to catch, kill, and sometimes eat as many of the trout as possible.

David Starr Jordan, Stanford University’s first president and the man who described the golden trout and bequeathed it its original scientific name, wrote in Sunset magazine in 1908: “Nothing in nature is more beautiful or more graceful than a golden trout . . . but already the local papers tell of the exploits of John Smith and his associates who caught four hundred and fifty golden trout with a fly in one morning, and of Peter Robinson who sent a box of three hundred and eighty home to his club. I do not write the real names of these folks because I do not know them and such people ought not to have any names — it is a waste of good atmosphere to call them anything.”

Jordan continues: “I read recently in the San Francisco Chronicle of five large parties which camped all summer on Volcano Creek feeding all the time on Salmo roosevelti. Another party reports leaving three hundred on the bank because they could not eat them. Trout hogs we call them but in doing so we owe a contrite apology to the relatively well behaved swine. Let us save the golden trout of the Sierra.”

Like Jordan, Evermann was appalled by what he found and called for an immediate ban on fishing for golden trout. He surveyed area lakes, rivers, and streams where goldens might be stocked in order to disseminate and thus save the species. His plan won the battle, but unwittingly planted the seeds that ultimately lost the war. With military precision and under government authority, golden trout were caught by trap, net, and hook and line and transported to area waters barren of fish. Over time, a system was established whereby in the late spring, authorities would pack into the high country, often under arduous conditions, to catch goldens and squirt their eggs and sperm into tin pots. While one technician dutifully held a hat or even his own shirt between the pot and the intense UV rays of the high-altitude sun, the egg and milt were thoroughly mixed, then the fertile eggs were packed into cheesecloth sacks and placed in a creek for several days to swell with water and harden into durable, peach-colored eyed orbs. The roe were placed in milk cans strapped to the backs of mules and carted out of the mountains to a fish hatchery on the valley floor, thousands of feet below.

In the hatchery, bathed in the waters of a clear, icy spring, the eggs matured and hatched. In the late summer, the tiny trout were poured back into the milk cans and packed by mules for multiday stocking expeditions into the high country. By the mid 1950s, the mules were replaced with aircraft that could plant dozens of lakes in a single morning and bring the pilots back to Lone Pine or Mammoth in time for lunch. By spreading the golden trout into over 300 lakes and hundreds of miles of Sierra streams, the threat of extinction at the hands of fish hogs was averted. The stocking resulted in anglers being able to enjoy the sport and splendor of the golden trout up and down the range. Angling was available to all, and bag limits accommodated the hungriest appetites. Evermann’s plan was an overwhelming success. Almost.

At some place, at some time, a horrible error occurred. Perhaps it even occurred more than once — no one really knows. Rainbow trout inadvertently got mixed into the pool of hatchery-raised goldens and under cover of broad daylight were planted into the Sierra side by side with their kissing cousins. Golden trout are descended from common ancestors of the rainbow and have no social mores about hooking up with their cousins, siblings, or even their own parents. The offspring of such a mixed wedding is called a “hybrid,” and it splits 50 percent of its genetics with a golden trout and 50 percent with a rainbow trout. If these mutants are allowed to breed among themselves, they produce what is known as an “introgressed race.”

Unbeknownst to the technicians, biologists, hatchery managers, and pilots, over a period of at least 50 years, they were mixing and remixing and planting and replanting introgressed golden/rainbow trout over the entire Sierra. In places that had been planted only with “goldens,” rainbowlike trout started to emerge. In my book Sierra Trout Guide, published in 1991, is a picture of a golden trout caught from one of the Alger Lakes in Mono County. It looks suspiciously like a rainbow, but the Algers are many miles from any known rainbow population and never had a history of being planted with rainbows. I posted photos of the fish to biologists across the West, and the common and completely honest answer at the time was that it was a “silver phase” of the golden trout. Today, with the aid of DNA analysis, we know a different truth — it was an introgressed fish where the rainbow trout genetics were overwhelming the physical characteristics of the golden trout. Having introgressed goldens in the Algers, a formerly barren trio of lakes some 100 miles north of wild golden trout waters, wasn’t planned, but it certainly was not alarming. Having introgressed goldens infiltrating the golden’s own native waters, however, is nothing short of genocide.

The South Fork of the Kern, Golden Trout Creek, and Volcano Creek are the natal waters of the California golden trout. The barren lakes originally identified by Evermann as being ideal refuges for the golden trout turned out to be their Achilles heel. Introgressed fish were repeatedly stocked over nearly five decades into Chicken Spring, Johnson, and Rocky Basin Lakes . . . all waters that feed into Golden Trout and Volcano Creeks.

A detailed search has ensued to identify populations of golden trout untainted by their rainbow cousins. Out of the entire Sierra Nevada range, about a half dozen pockets of genetically pure golden trout have been discovered. Unfortunately, nearly all these populations originated from a small handful of fish, and a century or more of inbreeding had produced fish that were even further removed from the original goldens than many of those that had interbred with rainbows.

Fortunately, the introgression was discovered before the entire reach of Golden Trout Creek had been contaminated. Fish from feeder lakes were blocked from entering Golden Trout Creek, then the lakes were sterilized. Though the upper reaches of the creek contain introgressed fish, the lower reaches still have genetically intact goldens. There is no way to test for genetic integrity in the field, and there is no practical method for identifying and eradicating the mongrels. The best-case scenario now is that, with the introgressed populations upstream eliminated, the rainbow genetics will be swamped by the golden trout’s, and the same selection process that created goldens from a rainbowlike ancestor will someday remove any trace of hatchery rainbow.

A much more serious problem exists in the South Fork of the Kern. Hatchery-reared and planted rainbows (and browns) had worked their way up the South Fork into the waters of the golden trout. At tremendous effort, a chain of fish barriers was erected between the heavily stocked lower reaches of the South Fork (today, only sterile rainbows are planted), but it was closing the door after the cows had left the barn. DNA analysis revealed the grim truth — the goldens of the South Fork of the Kern were highly introgressed. The problem is so pervasive that “monitoring the situation,” as is being done on Golden Trout Creek, simply isn’t an option on the South Fork. The fish in the system need to be replaced with purestrain goldens . . . doable, but no small task by any stretch of the imagination. Thousands of man-hours, millions of dollars, and unrelenting effort will be required.

The political challenges alone are daunting. It will be necessary to give the “founder” fish a blank slate upon which to reconstruct the species. The slate will need to be cleaned with the assistance of fish poison — most notably, rotenone. Rotenone is the most powerful tool in the fishery manager’s toolbox, and it is used only in the most critical situations. To rational people, saving a species from extinction qualifies as critical. To people such as Nancy Erman, Ann McCampbell, and their spawn of pseudoenvironmentalists marching under such banners as the Multiple Chemical Sensitivities Task Force of New Mexico, the extinction of a species isn’t profound enough to warrant the use of a piscicide. Over the past decade, these misguided crusaders have repeatedly derailed threatened-species conservation projects across the country with lawsuits and injunctions. In nearly every instance, the suits have been overturned, but the cost has been untold millions of taxpayer dollars and species increasingly threatened with extinction because of delayed mitigation. The strategy apparently is to drag out the legal process long enough for the species to disappear from the face of the earth. Then the use of rotenone is no longer relevant. There is little doubt the golden trout conservation management plan for the South Fork of the Kern will face years of legal delays.

If and when that plan is implemented, the decision of which fish will be allowed to play Adam and Eve and those that will be tossed on the bank will be entirely in the hands of humans. The alphabet soup of DNA will have to be balanced and weighed between various populations, then mixed and matched in a way that, the hope is, someday produces a trout that is like Evermann’s.

The progeny of Adam and Eve cannot be reared in a cushy hatchery environment — this is not how the original goldens evolved. Goldens are creek fish and will need to be subjected to the rigors of a shallow, high-altitude, fast-moving aquatic environment to reshape their DNA. Probably the single most important genetic filter of all is mate selection, and the new founders must be allowed to sort things out on their own turf, rather than be stripped of eggs and sperm by humans. Once the process is initiated, the going will be slow, and the temptation for further human intervention will be huge.

A century ago, golden trout were pulled back from the brink of extinction by management that was not popular with many of the citizens at the time. Today, goldens are again on the brink, and it will take extraordinary determination to resurrect the species. Fishery managers will need our unprecedented support to save Evermann’s trout. Give it to them.