There’s no question about it: The weather, while cooler than average this year, is still warm. Although we are headed into a time of year that, in many places, is considered fall, in California, late summer generally extends right to the end of October. What this means for the warmwater angler is that, barring a freak storm or series of cold fronts, the fishing is best during the early and late hours of the day, and the further you get into October, the better the topwater fishing gets.

While I was writing this column, I had to laugh. In the previous issue, Editor Richard Anderson quoted a friend of his as noting the seasons in Truckee, where this magazine is published, as being “almost winter, winter, still winter, and road construction.” If you live, as I do, in Southern California, you can expect the four seasons to be reversed. You get “almost summer, summer, still summer, and on a Tuesday in January, winter.”

The hot weather doesn’t actually last that long, but even though fishing for warmwater species takes quite a hit for a couple of months in January and February, for the most part, we get weather warm enough to fish for bass 9 to 10 months a year. For much of the year, in fact, we have weather that is too hot for decent angling in the middle of the day. You have to wait for the gentle hours of the early morning and the evening to get the good conditions that bring bass into the shallows, where you can really enjoy fishing for them. Not being a morning person, I prefer the later hours in the afternoon and into the evening for much of my warm-weather bass fishing.

Tossing a surface bass bug or popper in the evenings is great sport. As I’ve noted before, it is the warmwater angler’s version of dry-fly fishing. A few evenings ago, I was fishing a little pond in a local trailer park. Actually, we were supposed to be holding a casting clinic for my local fly club, but with the hot weather and the middle of the vacation season in full swing, only a handful of folks showed up. Since all of them were experienced casters and anglers, we decided to forgo instruction and simply went fishing.

This little pond has a mix of bass and bluegills in it. I never expect much when casting here. I’ve been told that the locals hit the pond hard with bait and take home the fish they catch, so I wasn’t concentrating on my angling. Still, it was a pleasant evening. Lengthening shadows sliding across the water and a fitful breeze gusting in spurts and dying in spasms made good conditions even better, giving the water the slight chop that provides cover for bass and encourages them to feed. Nevertheless, when the first fish struck, I was taken by surprise and almost failed to set the hook.

(This, by the way, is a good thing. Anglers whose reflexes are a bit slow actually hook more fish on top-water bugs than the guy or gal with razor-sharp reaction times. When a bass inhales a bug at the surface, it turns, and if you hesitate just a split second, instead of jerking the fly out of the bass’s big mouth, you do a better job of hooking the fish.)

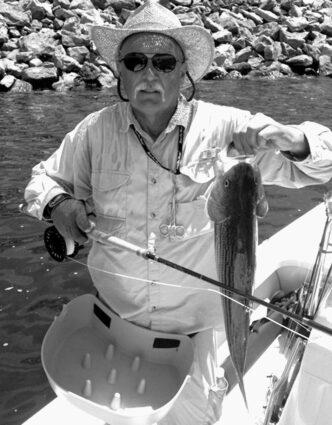

Actually, I caught two fish that evening. One came on a cork popper with wiggly rubber legs and the other on a hair bug. Hard bodies and soft bodies the two choices when fishing top-water bugs. Each has its uses, and each has a horde of fans who extol the virtues of their favorite bass-bug design.

I use both and try to fish the one most appropriate to the situation. By that, I mean selecting either a hard-bodied bug or a softer hair bug based on the conditions, rather than just grabbing one or the other out of my fly box. Let me stipulate here that you can catch bass on both kinds of top-water bug in just about any condition of wind or weather. It’s just that each type of bug has strengths and weaknesses. For the most part, I favor hard-bodied bugs in almost all of my angling. It’s not that I don’t fish soft bugs made of hair — I do. My reasons for choosing a hard-bodied bug first are usually that I fish waters that lend themselves more to the hard bug, with its higher survival rate in nasty surroundings. I’ve always looked to catch most of my bass in thick cover. This is especially true of fishing the heavily pressured waters of Southern California.

Hard-bodied poppers and bugs can be made out of traditional materials such as cork or balsa or more modern hard foam or plastic concoctions that will, for all practical purposes, last forever. They are rugged and can be shaped into cup-faced frogs, baitfish imitations, and other shapes that make a substantial amount of noise and commotion if manipulated correctly. Hair bugs, by contrast are soft to the touch and more fragile. Plus, they take a lot more effort to tie properly.

From the standpoint of the bass, most of my local waters are a kind of fishy nightmare. The water is usually very clear by bass standards, and clear water is a danger that bass worry about (provided, of course, that bass can worry). Clear water means the threat from overhead is maximized. Even very large bass never lose their sense of caution about being attacked from above. When they are small, bass are prey for all sorts of wading and flying predators. They quickly learn that being in clear water without overhead cover is dangerous.

The other thing that bass around my part of the state must contend with is the onslaught of watercraft. The water over their heads is a constant buzz of boats, personal watercraft, and what have you. This means that retreating into or undercover is pretty much standard bass behavior. Overhanging brush, trees, wind-flattened tules or bulrushes, floating logs or trash, boat docks — anything that provides a bit of concealment or protection — is where you will find bass during most of the hours in a day. Any bass fly you toss into such a place needs to be of stout construction. Hard bugs are, by and large, the best bet for this kind of fishing. Throwing a hair bug into a mess of floating sticks and moss is likely to strip the hair off the hook in short order.

Hard-bodied bugs also make a lot of noise. A good popping bug with a cupped face will create a noise and vibration that bass can feel for long distances. This is good for most of my local waters, where bass are hiding deep in cover or well back under something solid like a dock.

At Lake Perris one warm fall evening, my wife and I fished the marina area. We were just walking the rocky bank casting out toward the stern of the boats tied up on the docks. The boat traffic of the day was slowing to a crawl as evening set in, and the wind was just strong enough to put a nice ripple on the surface. By fishing a popping bug, we managed to “call” several bass out from under the docks and boats. The method was pretty simple. We just cast a popper into the shaded spot within a few feet of a dock or the stern of a boat and popped it fairly aggressively. Usually, the bug would disappear in a solid boil on about the third or forth pop.

As the evening deepened into night and the marina lights came on, we slowed the tempo, just twitching the popper enough to make little rings spread out across the now-quiet surface. By this time, the bass had moved out from the deepest shade of the docks to search for small bait along the shore, and we caught several fish right up against the rocks by just casting the bug out and twitching it along the rocks. This would have been a place where switching over to a hair bug might have made sense, because a hair bug drops to the surface with much less initial disturbance than a hard-bodied popping bug. By being gentle with the cast, we fished the hard cork poppers until it was fully dark.

Hair bugs, on the other hand, can work very well in brighter light. The main attribute of a hair bug is its light weight. Not counting wind resistance — they aren’t much easier to cast than a cork bug of the same diameter — a large hair bug may not weigh much more than a large dry fly. Stealth is a primary consideration in bright light and/or clear water conditions. The bass are skittish, and the splash made when a hard-bodied popper lands can spook them.

I’ve cast a hard-bodied popping bug to a spot and watched startled bass streak away. Casting a hair bug that settles to the surface leaving scarcely a ripple also may spook a nervous bass, but it won’t flee as far, and it will often return quickly to see what the thing was that fell on its “roof.” That’s the best part of fishing a hair bug. The amount of disturbance created is much less than with a cork or plastic popper, and you can use that to your advantage when the light is bright and the surface is quiet.

Hair bugs are a perfect tool for “do nothing” fishing. Merely casting a hair bug into a likely spot and then waiting is a killing bass-bug presentation. I can’t count the number of times I’ve watched as a dark shape slowly rose up under a nearly motionless hair bug. Sometimes the bass will hang there with its nose almost touching the bug, waiting for the slightest sign of life.

I particularly like hair bugs with rubber legs because of the habit bass have of inspecting things that alight on the surface. It’s almost impossible for a hair bug with dangling rubber legs to be perfectly still, and the slight quiver of a leg is all it takes to draw a strike. Sometimes that strike is a startling, all-out “whomp” of flying water and glittering scales flashing momentarily in the light. At other times, a bass, wholly confident it is feeding on some distressed critter, will sip down the bug with all the delicacy of a trout rising to a dry fly in slack water. Either way, it’s a hoot.

You still can create a fair amount of noise and disturbance with a hair bug, especially if the front face of the bug has been stiffened with silicone or some other substance, but the best part of hair-bug fishing is that they don’t pop and gurgle like a hard popper. While a cup-faced cork or balsa bug will make a great deal of noise, a hair bug looks and sounds much more like some living thing going about its solitary business. You can’t call bass from 20 yards away with a hair bug, but you won’t scare the wits out of them at 10 yards, either.

I’ve read that some anglers think a hair bug (and here we are talking about clipped or trimmed hair bugs fashioned from deer or antelope hair spun on the hook) creates a special swishing noise when pulled through the water. They also think this swishing sound is more natural. I can’t comment. I don’t have the ears of a bass. Still, there might be something to this idea. All those individual hairs sticking out at right angles to the hook must create some sort of sound or vibration that bass like. They certainly respond well to a hair bug.

Most hair bugs are tied to resemble frogs or moths or some other large, living creature that might find its way to the surface of a bass lake. A particular favorite bass bug of mine isn’t a bug at all, but a rodent. A deer-hair mouse is a deadly bass fly. You can fish a hair mouse in either dark or light conditions with equal success. The main thing is that a hair mouse just looks more like a living mouse than any hard cork, foam, or plastic mouse imitation ever invented.

A deer-hair mouse requires a different presentation than most hair bugs. Unlike a do-nothing hair bug simply deposit-ed on the surface and left there, imitating the action of a mouse that falls into the water means putting the hair mouse into motion almost the second it hits the surface. While I haven’t seen hundreds of swimming mice, I have seen a few, and almost every one of them wound up in the drink because they made a misstep in the branches of a bush that hung out over the water. When they fell in, they knew instinctively they were in danger and began swimming toward the nearest object.

That’s the difference in presentation: You don’t let the mouse lie still, nor do you pop it. When your hair mouse touches down, immediately start bringing it back to you with a series of short strips that keep the mouse moving without a lot of jerky action. You are after a smooth, rapid swimming motion. By the way, a mouse doesn’t swim on top of the water, but swims in it, with just its nose and the top of its head sticking out. A greased hair mouse floats like a cork. Better is a hair mouse that settles into the water a bit.

For my money, even though a well-dressed and clipped hair mouse is a work of the fly-tyer’s art, the best-fishing hair mouse I’ve used is the somewhat scraggly MouseRat design developed by Dave Whitlock. It fishes more like a live mouse than any other I’ve tried. You can buy them from a variety of sources, and tying instructions are available on the Internet.

If you like angling for bass with topwater patterns, then consider choosing your bug based on the conditions you face. By applying a little bit of logic, you’ll likely catch more fish and have more fun.