This article is not a hit piece against marijuana, people who use it, or those who grow it on their own property. This is an article about an armed invasion of foreign nationals sneaking onto American soil with the explicit purpose of producing drugs on an industrial scale — greater than 1,000 plants at a time. In the process, tens of thousands of acres of public lands are destroyed, and anglers, hunters, and hikers are kept away from them by threats of violence.

This article is about the time my wife, Lisa, and I were backpacking in a remote corner of the Emigrant Wilderness and came face to face with people who looked like they had choppered in from downtown Tijuana: ankle-length skirts, skintight pants, hard black city shoes, and an even harder look in their eyes. These people had a decision to make, and fortunately for us, they melted into the underbrush. This is an article about hiking and fishing a distant region of the Mokelumne River in the Stanislaus National Forest. A ranger at the trailhead offered that it was too remote and the elevation too high for pot growing. Along the way, we found irrigation fittings, and by the time we had returned to our truck, a 26,000-plant bust had gone down around us.

This is an article about how Lisa and I swam through the slot canyons of the Yuba River and, many miles from the nearest road or trailhead, came to a gravel bar pocked with fresh cowboy boot prints and littered with beer cans, trash, and a little girl’s bright yellow scrunchie — a family was living down there. We spent the night camping on the gravel bar, but with every snap of a twig or small pebble bouncing down from the cliffs, we were bolt upright and wondering where to run. An inescapable fact when swimming slots is that you can’t turn around.

The following day, we came upon a camp several miles and two thousand vertical feet from the nearest dirt road. This wasn’t a camp such as you’d see in the REI catalog. Mounds of propane bottles, tarps hung through the trees, half-gallon bottles of liquor, and a huge garbage pit betrayed the “go light” ethic. The campers were polite, but exceedingly helpful in showing us the way out.

This is an article about how, in the South Yuba River State Park immediately behind our house, the creeks go dry in the night, and the muffled hum of generators can be heard deep within old-growth stands of manzanita and poison oak. In 2007, 23,000 pot plants were discovered there, then 36,000 in 2008. A few weeks ago, another 30,000 plants were found nearby, and the overflight season that detects them has barely started.

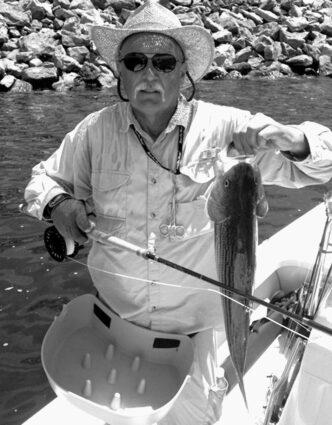

I now carry a .38 when fishing or hiking in remote country. It weighs only a few ounces, but it weighs on my mind more than the sum of everything else in the pack. I won’t admit to being afraid, but am seriously aware of my surroundings in a way that would have been inconceivable only a decade ago.

Small-town sheriffs running for office and newspapers looking for a headline shout that industrial pot growing is the product of the violent cartels of Mexico. This is rarely the case, but the reality is hardly reassuring. I met with and personally asked Obama’s drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, about the cartel connection in California’s industrial grows, and his answers were evasive and pointedly noncommittal. Ray Mooney, the deputy director of public affairs for the U.S. Forest Service Region 5, said their agency’s law-enforcement branch has never made a connection between industrial grows and the Mexican cartels. Patrick Foy, game warden and public information officer for the California Department of Fish and Game, says he has never seen any cartel connection.

Does this mean that private industrial grows are safer than if they were outsourced by the Mexican cartels? Probably just the opposite — cartel operations are orchestrated from on high, and violence is used as a means to an end: to intimidate authorities, secure territory, and manipulate local politics. The cartels have made an effort to keep their overt violence south of the border. The last thing they want is bloodshed on American soil, which would undoubtedly bring immediate calls to wake the sleeping giant.

Industrial grows on California’s public lands are typically run by a close affiliation of family and friends, almost exclusively Mexican nationals. These relatively small drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) don’t see the big picture through the lens of a cartel and are probably more willing to resort to violence than might a cartel satellite instructed to lay low. Authorities and media trying to incite the public by playing the cartel card might get more bang for their buck if they dropped the simple sound bites in favor of telling the more complex, yet perhaps scarier truth.

At least in California, American citizens have pretty much vacated the forest when it comes to commercial pot growing. With the advent of Proposition 215, anyone who wants to raise pot can easily obtain a handful of doctor’s recommendations and semi-legally grow from the comfort of their own home. Mexican nationals are understandably wary about entering “the system,” and applying for a 215 is a nonstarter for them.

This past July, a multi-agency task force raided pot grows across the forests and parks of Madera, Fresno, and Tulare Counties. Nearly half a million plants were found at over 126 grow sites. Out of 97 suspects arrested, 94 were Mexican nationals, and the majority were in this country illegally.

The preponderance of Mexican growers has put politically sensitive authorities between a rock and a hard place. In 2009, the Rockies experienced a dramatic increase in the size and scope of its pot busts — virtually all run by or employing Mexican nationals. As a result, Michael Skinner, the assistant agent in charge of the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Region, released an emergency bulletin warning users of public lands to be alert for tortilla wrappers and Tecate beer cans found off the beaten path. Immediately he was charged by Latino organizations with racial profiling and was forced to retract his words. Since then, the USFS has done backflips to defuse any associations between any specific nationality and industrial pot growing.

This July, following a 76,000-plant bust in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, the USFS issued an official press release stating that it had arrested a “displaced foreign traveler.” The innocuous sounding “displaced foreign traveler” was an armed felon illegally in this country from Michoacán, Mexico.

A Shasta County deputy I spoke with couldn’t hide his irritation. “The federal government is going to get innocent people killed because of its unwillingness to provide the public with factual information. If my wife and I are fishing a remote stream and I find a Clif Bar wrapper, I’ll pick up the garbage without a thought. If I find a tortilla wrapper, I’ll turn tail and head the other way. It is a big deal.” And this guy carries a gun.

Guns are synonymous with industrial grows. USFS special agent Michael Gaston said, “Almost every grow we go to we’re going to find weapons.” Weapons range from .22 pistols, to sawed-off shotguns, to AK-47s, to sniper rifles filled with rounds hand-loaded for long-range targeting. Mike Fisher, who sold his fly shop in Nevada City to become a counternarcotics detective for the Sierra County Sheriff’s Office, encountered an industrial grow near Downieville that was protected by an arsenal that included an SKS assault rifle (with bayonet mount), a 12-gauge shotgun, a .45 handgun, a 30.06, and a Ruger 10.22. The grower told him the guns were to shoot gophers and to hunt deer for food. Mike grinned, “I would have believed him, but he didn’t have any deer tags.”

Weapons are primarily kept for defending the plants from pot pirates. I was talking with a grower in 2009 when an airplane droned overhead, flying low and slow. He recognized it as an aircraft that the government normally uses and was outwardly unconcerned. His bigger fear was for the planes rented by pirates who cruise the forests to GPS grows, then come back in force to raid the crop.

Raiding the crop, or “cutting the grass,” as DFG wardens like to put it, has experienced a paradigm shift over the past several years. Despite billions of dollars spent on drug enforcement, pot is of higher quality, more available, and less expensive than at any time in history. A pound of weed that sold for $5,000 in 2008 might fetch $2,000 today. The market is flooded. Despite ebbs and flows in demand, consumption of weed is now roughly the same as it was in 1982, when Nancy Reagan unveiled the “Just Say No” antimarijuana education program. The war on pot has, by any measure, been lost.

In the recent past, the government would proudly count coup and put on display its increasingly huge busts — an incredible 300 percent increase between 2005 and 2009. In Washington, this was presented as proof of a strong eradication policy, but at the field level and in the public eye, it was seen for what it really was: a metric of the vast and rapidly escalating scale of pot production on public lands that the government is powerless to slow. In June the team of government agencies involved in the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas program (HIDTA), which is tasked with analyzing data regarding illicit drug trade, concluded “The outlook is clear — expect greater marijuana production each year until market equilibrium is reached; that is, when demand equals supply.”

Today, efforts are being redirected toward education and away from simply cutting the grass toward performing environmental assessments and rehabilitating the land. Where pallets of fertilizer and pesticides would rot in the winter rains and spill into the watershed, they are now removed. Miles of irrigation pipe are painstakingly collected and packed out of the backcountry, instead being left in place to be reused by the next year’s growers. Citizens’ organizations such as the High Sierra Volunteer Trail Group are working alongside law enforcement to reclaim the forests.

Weed eradication efforts themselves have not abated, but in fact have taken a turn for the violent. Veteran USFS agent Russ Arthur notes, “In the past, when we dealt with marijuana, it was with compliant American citizens, typically locals, growing small amounts.” Today’s massive crops are worth millions of dollars, and with increasing frequency, law enforcement officers are engaging in shootouts with growers.

A game warden investigating deer poaching in the Santa Cruz mountains was shot through both legs by an industrial grower using a high-powered rifle. Last summer, two Lassen County deputies were shot by a grower with an AK-47 as they approached an 8,000-plant crop north of Eagle Lake. In the last three weeks alone (this was written in early August), game wardens and officers have been in gun battles on public land industrial-grow sites in Mendocino, Lake, and San Mateo Counties. In all three shootouts, suspects were killed. Two weeks ago, at an 8,000-plant grow in the Tehama Wildlife Area, DFG game warden Scott Williams tackled a suspect who was drawing a 9-millimeter handgun from his sleeping bag.

There has yet to be a hiker or angler shot on public lands by pot growers, but run-ins are increasing, violence is escalating, and it is inevitable that an angler, hunter, or hiker will be killed, probably sooner than later.

Despite the very real danger to law enforcement officials, I have been repeatedly amazed at the professionalism and empathy shown by many of them toward the growers. Though they maintain a very professional command presence, they treat their suspects with a great deal of dignity and even respect.

Industrial pot growers are not only keeping outdoor enthusiasts from enjoying public lands through fear, but are destroying the wilderness itself and its resources. In the Humboldt National Forest, I was at first underwhelmed by the environmental damage I saw when walking into a camp. Several small springs had been diverted, there was minor erosion where terraces were cut into the hill for crops, and a few trees had been felled to allow sunlight to reach the plants.

It wasn’t until I started following the drip lines that I realized that “a few trees” here and there was actually translating into thousands of trees as I hiked along miles of tubing irrigating patches of pot. Most of the oaks, madrones, and fir trees hadn’t actually been cut down, but were girdled with machetes so that the crop-shading leaves and needles would drop. Standing snags aren’t as obvious as cut stumps to aerial surveillance.

Marijuana is a thirsty crop. A 380,000 plant grow requires lots of water and competes directly with native fish, animals, and plants. The water comes from springs and streams. Growers will dam a creek and at night divert the water into plastic-lined pits dug in the ground. Come daylight, the creek is flowing again, and the crops are discreetly irrigated from the cisterns. Of course, many fish die in the process.

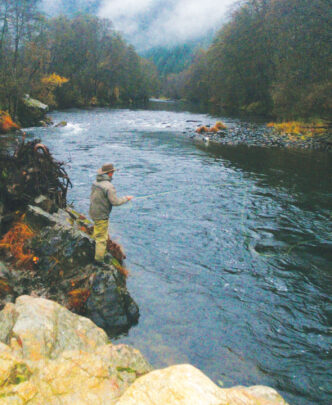

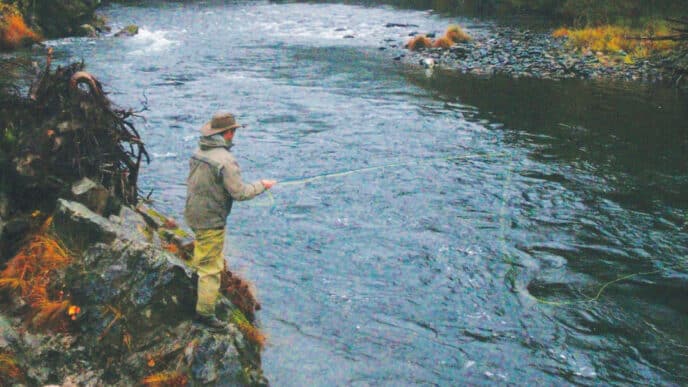

Detective Mike Fisher was alerted by anglers in Sierra County that trout had disappeared from a creek that normally had an abundance of fish. Mike used the excuse to grab his fly rod. A mile upstream, he found that water from the creek was being siphoned into 50-gallon drums that irrigated a series of large grows.

Not only are creeks used to irrigate plants, they are frequently diverted into pools where fertilizers and herbicides are mixed in batches, then piped to the crop. When residual toxins are released back into the creek, it wreaks havoc. Fish and Game agent Patrick Foy told me of anglers who reported seeing dozens of dead fish in a creek running alongside a Forest Service road. A warden investigated, and nearly two miles upriver, he found a pesticide batch-mixing pond behind a small dam in the creek. The pesticide of choice of industrial pot farmers is Furan. Furan is an extremely toxic organophosphate poison made in Mexico and illegal for use in the United States. Mexican nationals rightfully claim it to be muy fuerte — very strong. Near Yosemite, about a quarter of a mile downstream from a growing operation, an officer rinsing the dust off his face in a creek was dropped to the ground. Fortunately, a helicopter was nearby, and he was evacuated to an emergency facility, where he was treated for acute organophosphate poisoning.

Furan is not only effective for killing aphids and spider mites on plants, but is routinely used by cattle herders in Africa to rid the land of carnivores. A little Furan sprinkled on a carcass is enough to kill an entire pride of lions. In our parks and forests, growers put out unused batches of Furan to poison deer, bears, raccoons, and other animals that might drink it. Rats, mice, and rabbits have a penchant for chewing irrigation lines, so growers also scatter poison liberally along their lengths. The poisoned and sick animals are easy prey, and their predators get poisoned second-hand.

Animals that aren’t killed by poisoning or the dewatering of their habitat are simply shot dead. The remains of species from ringtail cats to black bears are routinely found at industrial grow sites. Many of the animals are left to rot, but just as many are eaten. At a grow camp near Kings Canyon this summer, a bald eagle was found shot, gutted, plucked, and hanging by its feet in preparation for being added to the evening meal.

The days of wandering blissfully unaware cross-country through our public lands are gone. Even elevation is no longer an ally. Last year, 30,000 plants were seized near 8,000 feet in the eastern Sierra, and a large grow was found at 9,400 feet in the White Mountains. Paths that pop up in the middle of nowhere are suspect. Normal game trails are about 6 inches wide. Anything wider than 10 inches is made by cattle or humans. As a Forest Service ranger told me, “When you see a 10-inch trail materialize from several smaller trails, your radar should be on. The moment that trail goes over a log or hops on a rock, you know it wasn’t made by a cow.” Black plastic tubing is a dead giveaway. It leads somewhere, and that is somewhere you don’t want to be. Animals disperse trash piles left by growers, and any litter you encounter in the middle of the forest should amp your situational awareness. Scattered tortilla bags, yellow Pato tomato sauce cans, and pink (shrimp) Ramen wrappers are synonymous with grow sites across the state.

The days of wandering blissfully unaware cross-country through our public lands are gone. Even elevation is no longer an ally. Last year, 30,000 plants were seized near 8,000 feet in the eastern Sierra, and a large grow was found at 9,400 feet in the White Mountains.

If you come across a grow or encampment, don’t stop to sample some bud, to snap photos, or to make a GPS waypoint. Chances are good that you are being watched, perhaps through a rifle’s scope. Simply put your head down and walk away. You aren’t going to save the world by pulling out the iPhone to call in the troops, but you may save yourself by acting uninterested and blissfully unaware. Memorize the location, but make your call later.

Of 43 million acres of public lands in California, official estimates are that 390,000 acres are affected by cultivation of marijuana. That is a bit less than one percent of the total acreage: Growers want to be found even less than you want to find them. So stick to travelled trails and fish the main-stem rivers and creeks. Be aware of your surroundings, use common sense, and have a great time.