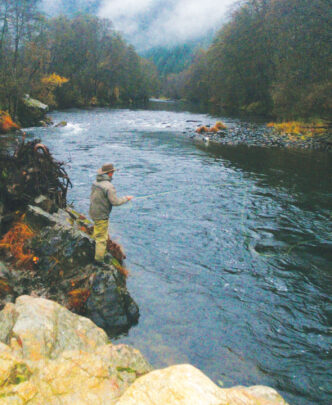

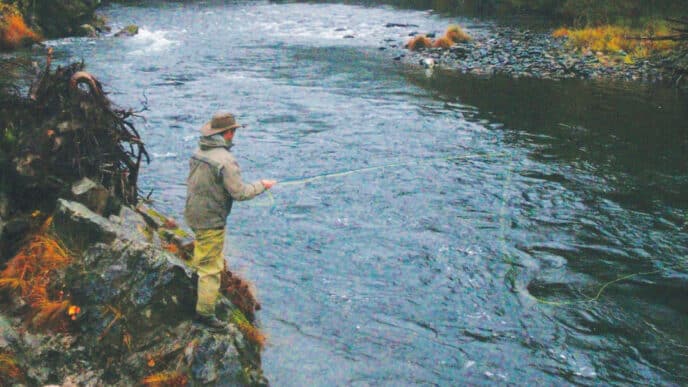

The river’s famous, and I’m holding my own, slipping downstream after the morning drift-boat hatch while raising fish, here and there, with a big green Humpy. Summer grasses reach head-first for the water, and beyond the banks, squalls of young grasshoppers erupt along the trail. The sun leaves the tops of the tall cottonwoods and at some point ceases to rise, soaring west across the blue, opaque sky.

I get two heavy rainbows by wading deep into a wide eddy beneath an island, drifting the fly at the end of long casts along the edge of the main current. While I’m landing the second fish, a guy shows up at the bottom of the island and makes a big stink, to his buddy, about me standing in the exact spot where the fish are.

“Guy gets his first pair of waders and he thinks he owns the river!” he hollers, keeping his head turned as though I’m not supposed to hear.

I release my fish and blow on the Humpy to dry it. I can see the guy has a strike indicator on his leader — a different approach to this fair and blossoming day. Naturally, I’m insulted by his show of scorn — Didn’t he just see that fish! — while at the same time, I know better than to invest one bit of time or emotional energy defending my old-fashioned game.

A couple of little weighted nymphs drifting through the eddy where I’m standing certainly would work.

Instead, I swing the head of my line out of the rod tip and, gently as I can, set the fly, in the guy’s direction, back into the current, where it rides, prettily, my way.

Famous rivers, I remind myself, can be a bitch. You learn to take what you can get.

After lunch and another mile of river, I slide into a long channel running behind another island, water you’d never fish or even find from a boat unless you already know it’s there. Which is probably only fifty guys today, I immediately calculate, considering the number of boats that keep drifting by. Oh, well. Yet sure enough, up along the inside edge of the current, right at the top of the channel where a boat swinging in would be turned around, guys casting at the other bank, the big Humpy gets eaten by a very big trout — one of those takes that’s so slow and so confident that besides being the loveliest sight the sport has to offer, it immediately inspires your deepest fears, because you know, by this time, how genuinely big the fish in this river can get and the weight through the rod feels absolutely insane as the shocked and astonished trout gets directly into the heavy current that created the channel and now just acts pissed as it blows downstream in a headshaking, cold-blooded huff.

I try to regain some control.

Oddly, in the midst of first chasing and then fighting the fish, I twice hear guys in passing boats holler, “You need a net?”

Turns out they’re not talking to me.

Everybody, it seems, catches fish here.

This one, when I finally land it, seems about as good as they get, a great slab of trout with all the brilliant features the family shares, as precious in every way as the details of a musical instrument you’ve learned to play. The river, too, has begun to take on that subtle appearance of great water you’re falling in love with even though you don’t yet know much about it. It’s just big and wide and full of the color of the sky — and apparently full of a hell of a lot of big trout, besides.

At the bottom of the channel, where I free the fish, I notice there’s this weird triangulation of currents created by a break in the tail of the island.

If things have been fishy up to now, this could be the Buddha’s navel.

But it’s deep — more like a swimming hole than a spot to get fish that aren’t rising to move to the dry fly.

I’m easy — and interested, too. So I reconstruct my leader into a nymphing rig, sans indicator, and run a little Wild Hare and green Sparkle Pupa down the slot, allowing a bit of weight between the flies to keep things tight, which I sort of lead downstream with the rod tip in that way so many of us have mastered, in one form or another, over the years.

Only one problem: I forgot to remove the 5X.

AndI swear I hardly even leaned on him! I whine, a little while later, to no one in particular while reconstructing my nymphing rig again.

The next time that I break off, I fabricate an excuse that has to do with the depth of the grab and all that line underwater, so that you can hardly ease off enough, and a big trout, in the current, is virtually unstoppable.

It’s kind of embarrassing.

Anyway, I’m 0 for 2 in the hole, not exactly fishing how I like to fish, but it seems like I should at least land one here before I head on my merry way.

And, besides, the sun is out, the swallows swirling, the hot, dry breath of the West fragrant with cottonwoods and sage — and one of these days, maybe sooner than later, I’ll be too old to wander along a new river and cast a fly, even two, and see what happens or what I might find.

I’m halfway through rerigging again when I glance downstream, and there, in a patch of dead water where the current below the deep hole suddenly bends and reconfigures and heads back toward the main course of the river, I notice, in the long slick lying right beside a steep bank of tall willows, what appears to be, from this angle, a gang of sea otters poking their heads up and down through the surface . . . or maybe it’s the ticking of a big kelp bed moving up and down in the . . . waves?

No, those are trout, I tell myself.

Holy shit, I think.

I hold still long enough to get the scale and perspective right. What I’m looking at, I finally realize, are the snouts of two or three dozen trout rising up and down through the surface as though crates of jettisoned cargo bobbing again and again into view.

They look like black triangles, slightly rounded at the top, moving up and down like kids on a carousel.

They look like big friggin’ trout feeding like crazy.

I gather in my nymphs and head downstream.

Coming around the willows, I enter the periphery of a fog of little black caddises. This is no time to get technical. They’re small. They’re black. They’re caddises. I happen to have some of those.

I rebuild the end of my leader, lengthening it with both 4X and 5X. I tell myself to stay cool. The fly I tie on looks good, not perfect, but the size is right, the profile close. The real bugs, I can see, are resting on the slick water, just sitting there, and the trout have moved out of the current and are feeding. It’s sort of obscene — either a great bacchanalian feast or a slaughter of biblical dimensions. The bugs look like whiskers on the water. The trout are big, and they are eating.

Fortunately, I pay attention to what I just told myself, and I don’t let my excitement get the best of me. There are so many fish feeding that it’s difficult to pick out just one, to figure out what it’s doing. I’m pretty sure there’s absolutely no way to make this work unless I aim directly at a fish’s nose. They’re not going to move one way or another for the fly. They’re going to get a perfect look at it. I make half a dozen short casts, trying to get the distance just right, the leader to fall perfectly straight. Every time a fish rises anywhere near the fly, I lift the rod, and when there’s nothing there, I back cast once and put the fly down again, aiming for another snout.

When I finally lift and connect, it feels like I came tight to a brick that’s now sinking and now ripping line off the reel.

Holy Jesus, I think.

They’re all big. They’re all good. Rainbows and browns both, feeding right together so that, after a couple of each, I begin to wonder if I can tell them apart by the way they rise or take or fight. I haven’t a clue. The light is low, funky, everything taking on the same shade of gray. I can’t even really see the fly, only the spot it should land as the leader falls at that certain distance from the end of the line. I see a fish rise, and my rod goes up as if to ask, as Dave Hughes says, “Is anybody there?”

When there is, you sure as hell know it.

What’s most startling to me is that the fish just keep right on feeding — even after I’ve clomped around fighting and landing a few. I move up higher in the pool, and then I move down low. I wonder if my buddy from earlier in the day would suggest I’ve positioned myself all wrong. I wonder if I’ve owned more pairs of waders than the number of years he’s been fishing in his life.

But who needs thoughts like that?

The water is crotch deep, dark as shade, and still — except for the feeding trout. Near the bank after failing to stop a fish that headed directly upstream, never once pausing until the hook pulled free, I notice that both legs of my waders are discolored, thigh to calf, by a dark-green film — two slimy bands of green caddis pupae, pressed together tight as seeds in a tomatillo.

I’ve got plenty of those, too.

Yeah, right, I think. As if this — casting little dry flies to big feeding trout — isn’t precisely what forty years of fly fishing has taught you to do?

In the morning in camp,I set up to tie a dozen of my Little Black Caddis. My lineup has taken a beating. I’m also devoted to the notion that after you’ve actually seen a hatch on a new river, you can do better than with the flies you brought, no matter how well the pattern you used has worked.

Of course, if I had genuine responsibilities I was supposed to take care of this morning, I’d be perfectly OK with returning to the river, later on, with the flies already in my caddis box. But isn’t tying flies in camp while drinking coffee in the cool of the morning while the oats cook and the quail hurry by and the scent of the soil rises with the sun like your anticipation of a hatch like yesterday’s yet another reason you’ve been at this all this time?

Here’s what I do for a Little Black Caddis. On a size 16 or 18 dry-fly hook, I tie in what amounts to about a third of a strand of black Antron yarn, which isn’t really black at all, but more like root beer or chocolate. I twist the fibers and wind a slender body. For the wing, I use moose hair; it lies flat, never flaring like deer or elk hair, so it gives you the right profile, as well as a dark color. For the hackle, in front of the wing, I use two or three winds of something undersized and brown.

That’s it. It’s a simple tie, and I crank out all dozen, six 16s, six 18s — and then six 14s for good measure — in the time it takes the oats to cook. By then, I’m also on my second pot of coffee, which is OK, I figure, since I expect to spend about eight hours on the water, if things go like yesterday.

If they don’t, I suspect something else good will happen — another chance to do this my own way.

Which is the best reason of all, I think, for enjoying this silly game.

Little Black Caddis

Hook: TMC 900 BL, size 16 to 18

Thread: 8/0, black or camel (the latter has a color that is close to cocoa or dark allspice)

Body: Black Antron yarn

Wing: Moose hair

Hackle: Brown