Mid-September makes it official: autumn has arrived. From where I sit, it’s about time. I have nothing in particular against the other three seasons, though two tend to be too wet and the other too hot, but autumn is special. Of course, if it’s as goony as this year’s spring and summer, there’s no predicting what sort of weather we’ll actually have. The only thing certain is that for some of us, at least, September means a new steelhead and salmon season has begun in earnest.

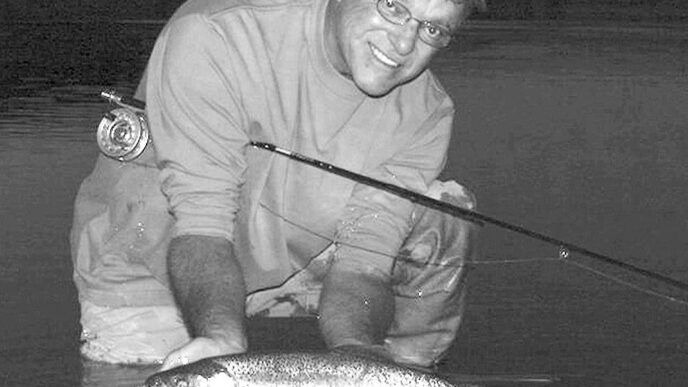

Years ago, when my steelhead addiction first surfaced, most of my fishing was on coastal streams, from the San Lorenzo River in the south to the Smith in the north. It began in late September for king salmon, in mid-November for steelhead, and ran through the end of February or so, though some rivers were open all year. This was frequently in or not far from the tidewater, and the prevalent technique was (and still is) to swing a fly through pools where steelhead or salmon hold while waiting for rising water to give them access to spawning sites upstream. Long casts and weighted flies in the range from size 6 to size 2 were frequently required, and rods tended to be hefty fiberglass 9footers that cast sinking shooting heads in the 9-weight through 11-weight range.

Longer inland streams, such as the Trinity, Klamath, and Rogue, also had impressive runs of steelhead, as did the North Umpqua and the Deschutes. These were farther away and involved covering more river miles to find fish, but the steelhead in those rivers would frequently look up at a lightly sunk or even floating fly. An 8-1/2foot rod was fine, but when the advent of graphite made longer rods practical, few of us thought to use anything shorter than 9 feet. A 7-weight or 8-weight floater or sink tip was the line of choice.

It’s a different game today, though we play it on the same rivers. The most obvious change is the current prevalence of long two-handed rods, particularly when fishing inland streams where a floating or lightly sunk fly is effective. Even on the Trinity, where casts rarely need to go past 70 feet and many casts don’t need even that much distance, a two-hander seems de rigueur. ( Jim Freeman, the outdoor writer for the San Francisco Chronicle through the 1980s, once opined that the Trinity is the perfect stream for an 8-foot rod.) In part, the popularity of two-handers is due to their effectiveness and ease of use, but as with many activities, having the latest gear and looking like you’re in the know seems just as important.

Evolving Rod Preferences

What two-handers do, by spreading the work across both sides of your body and to both hands, is minimize the effort needed to get a fly to where the fish are. They can pick up and cast substantial lengths of line easily and without multiple false casts and do so in situations where there’s very little room for a back cast. Master a couple of different Spey casts, and covering the water out to 90 feet becomes surprisingly easy. The big guns add 20 feet or more to that.

Are double-handers really necessary? I guess that depends on how you think about it. If efficiency were the only test of steelhead tackle, we might all be fishing bait under big floats with spinning gear. There are clearly other considerations to take into account.

Two-handed rods and Spey-casting techniques are terrific choices on larger rivers, where long casts are needed and there’s room to swing a long rod. And of course, you can always fish them at shorter distances. The lines used on two-handed rods, heavier and larger in diameter than comparable single-hander lines, also lend themselves to casting large flies. Then again, any competent caster should be able to reach 70 feet with a single-handed 8weight, and huge flies aren’t always needed when fishing for steelhead.

In addition, casting with doublehanded rods is great fun. There’s just something innately satisfying about the feel of a long rod loading and unloading as you put a bend into it while that loop unrolls way out in front of you. You watch it happen, fish through the drift, and set up to do it again, though it’s never the same cast when you repeat it, so it’s always a new challenge. To put a bit of a woo-woo spin on things, casting a double-handed rod is sensual as hell. Of course, that’s also true of casting well with single-handed rods. Maybe it’s just that there’s more rod to get working with a two-hander, and the cast seems to unfold more deliberately, so there’s more to appreciate.

I like fishing and casting both types of rod, but I frequently get the impression that much of the Spey revolution is as much about learning something new, with a new language, new gear to acquire, and that pleasing feeling of being part of a club that’s, if not exclusive, at least a little bit arcane. Ironically, that’s the way steelhead fly fishers thought of ourselves thirty or forty years ago as we waged our purist struggles with the bait and spin fishers. To be fair, it was likely also how spin fishers thought of themselves as they discovered the joys of ultralight rods and monofilament in the heady years after World War II. To a greater extent than with singlehanded rods, double-handers have developed a number of different casting and fishing styles and different rods and lines to go with them. Fast rods, slow rods, long lines, heads, floaters, and sinkers are all part of the game with single-handed rods, but aficionados of two-handers, developing good gear in different conditions, have come up with three different styles. Should you, for any reason that suits you, choose to join the double-handed club, you’re going to have to decide just how you want to fish and then pick your tackle accordingly. You can choose a conventional, moderate-action Spey rod, which has its roots in the British Isles, which you’ll fish with a relatively long line such as a RIO Windcutter or Airflo Delta Spey, to name just two of the score of possibilities. Repeated long casts without having to retrieve any line for the pickup are the advantage here. Or you can choose a faster-action “Scandi” (Scandinavian) double-hander, which you’ll fish with a shooting head of 40 feet or so and a lightweight shooting line. As with single-handed shooting-head casting, each cast you make with a Scandi head requires retrieving all but the head back past the tip top. Scandi rods tend also to work best when fishing floating or slow-sinking lines.

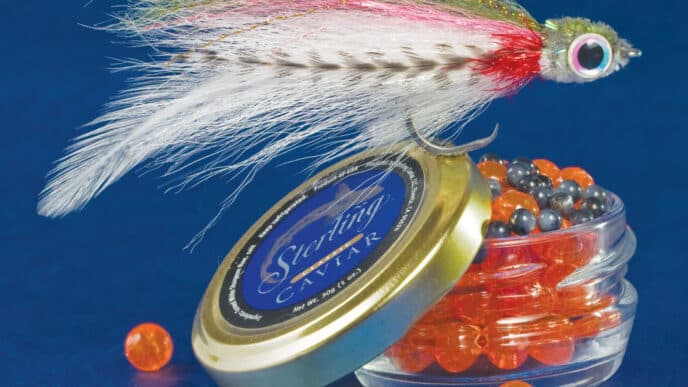

Finally, you can choose a “Skagit” double-hander, a rod with strong tip and relatively soft butt that’s designed to cast heavy, specialty shooting heads and fast sinking tips, often with large, weighted flies. Our brothers in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia are responsible for developing these. As with Scandi heads, you’ll have to retrieve all your shooting line each time you cast, but you’ll set up the cast in a different way and can honk out and sink some humongous flies with this technique.

Except on really big rivers, and we’ve really not got them in California, unless you count the Sacramento and the lower reaches of some northern streams, the 14foot 9-weights and 15-foot 10-weights of a decade ago have ceded their primacy to 7-weights and 8-weights and even to 6weights, all in the 12-to-14-foot range. Those line weight numbers are a bit deceptive if you’re used to single-handed rods, because there are different standards for two-handed lines. The lighter of my two double-handers is a 12-foot 6-inch model that the manufacturer describes as for a “5/6 line.” What that means in Speyspeak is a specialty 21-foot Skagit floating head of just under 400 grains that’s looped to accept additional tips of various densities. A weight like that makes the combination significantly heavier than what we would designate as a 12-weight in a single-handed line, which is 375 grains for the first 30 feet, per AFTMA standards.

Call it what you will, the mass of even that 5/6-weight Scandi line is more effective propelling flies of greater size and bulk than any 5-weight, 6-weight, or even 8-weight single-handed line, and it’s a lot of fun. Whether it’s more fun than making a satisfying cast of 80 feet with a singlehanded 8-weight and a long-belly floating line or 100 feet with a 10-weight single-hander and a sinking shooting head is something you get to decide for yourself. Tomaytoes, tomahtoes and all that.

Where double-handed rods are generally not welcome is in the lineup of anglers on many coastal winter streams — or early summer shad rivers, for that matter. The long rods and the long downstream drifts of their lines take up a lot of space in what’s often a tight, but social crowd, and the surface disturbance created by many Spey casts is no more welcome than a rock tossed into a pool that holds fish. Here’s where that single-hander of 9 to 10 feet, the one that casts a 300-grain intermediate or sinking shooting head of 30 feet or so, will stand you in good stead. And yes, you might get away with fishing a 7-weight or 8-weight single-hander, but when the wind is blowing on your casting arm and you’re butt deep in the river fishing a heavy size 6 fly, you’re going to wish you’d brought the bigger stick. Or, to be honest, a two-hander, if you can find the room.

How about switch rods? These are neither true single-handed nor true double-handed rods. They’re generally only 10 feet 6 inches to 11 feet in length, with a top grip that’s half or more again as long as that on a single-handed rod, with another 3 inches or so of grip below the reel seat. They can be cast single-handed or, when you want to save your arm or execute a two-handed cast of some sort, you can bring the bottom grip into play. Some folks love them, some hate them. One rod designer friend describes them as poor compromises bought mostly by folks who are leery of learning real two-hand techniques. Others describe them as incredibly useful angling tools. My experience is that an 8-weight, 11-foot single-hander is no great burden when casting single-handed, and it’s more effective than most 9-footers when making modest Spey casts. I’ve also fooled around with one as a double-handed overhead rod with sinking heads and mono shooting line. It was a distance monster. That opens some possibilities, particularly for high water on winter streams. You’ll want a couple of different lines for the switch rod — a standard weight-forward 8-weight, for example, for singlehanding, and line that’s heavier by a couple of line weights for double-handed work.

Rigs for Regional Waters

So, given the wealth of choices out there for fishing for steelhead in California and southern Oregon rivers, what’s a serious angler’s basic arsenal going to look like? My votes go to three choices.

The first is a 9-to-10-foot singlehanded 7-weight or 8-weight graphite for a floating line and light sink tips for use on inland streams such as the North Umpqua, Trinity, Rogue, and Klamath. You can get away with a 6-weight on the Trinity, but even a 7-weight is frequently undergunned on the North Umpqua. A multitip line (where the line ends in a loop 10 or 12 feet from what would normally be the tip, so you can add tips of different density) is a great choice here.

Depending on your state of mind vis à vis single-handed or two-handed fishing, this is a rod to be used interchangeably with a 12-to-14-foot double-hander that fishes the appropriate multitip 6-weight or 7-weight specialty Spey line of 450 to 550 grains, with multiple tips to address different types of water and different depths. Fortunately, most rod companies make double-handed rods with actions that will let you cast and fish effectively with either a traditional Spey line or one sort of head of another.

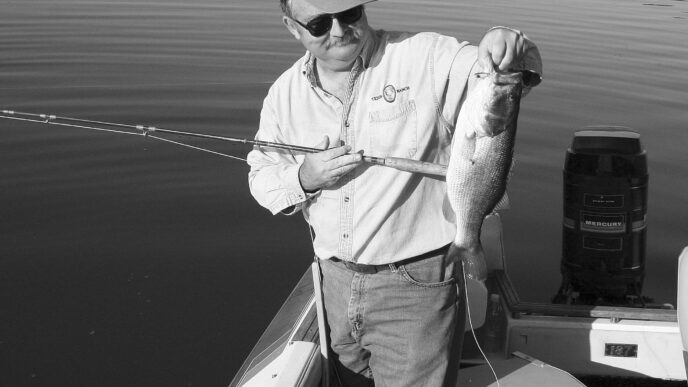

Last, but not least, I would add a progressive-action 9-weight or 10-weight graphite single-hander that will handle sinking shooting heads in front of mono shooting line. You might make your lighter rod do double duty here, but I’ve found myself happier with a second dedicated shooting-head rod that’s both a little shorter and a little beefier. Anything longer than 9 feet is awkward when fishing from a pram, but a longer rod is nice when wading. Uplining by two line weights over the rod’s listed weight is the normal rule when using heads, and while that works fine for me when fishing from a pram, uplining by one line weight works better for me when wading.

Those are the basics, and if you’ve somewhat different notions, good on you. If you’re hopelessly addicted to chasing steelhead, though, you’ll likely also want to pick up a dedicated Skagit double-hander of 14 feet or so, one that handles a 550-to600-grain head and sinking tips and lets you fish big flies way out there and deep. Also a 9-foot 5-weight or 6-weight for fishing half-pounder runs in the early fall. OK, you already own that one for trout. See how inexpensive this sport is? Then add a 12-foot or so double-hander that casts a very light Spey line in the 350-to400-grain range — what the rod manufacturers describe as a 4/5-weight or 5/6weight. One of my friends tells me this is absolutely the last rod that any real Spey fisherman would choose, but it’s simply great fun to go light sometimes. And if you’re tempted to use it for trout fishing, well, shame on you.

Finally, to touch base with the golden years of California steelheading, you’ll want a vintage fiberglass 9-foot Fenwick, Winston, Claudio, Fisher, or Lamiglas 10weight. Heavier in the hand than your graphite single-hander, it’s a bit of angling history that you can still fish all day. You’ll also love it for fishing from a pram, where the resilience and lifting power of fiberglass have always seemed to me more preferable than graphite.

Of course if you’re truly into all this, you might also consider a 9-foot or 9-/12foot Winston or E. C. Powell bamboo for the same line weights. Folks were taking big anadromous fish with them when graphite was for pencils and fiberglass was a glint in a lab rat’s eye.

Lines? For the single-handed inland rod, you’ll want a weight-forward floater with a long belly for easy mending and maybe a sink tip or two. For the coastal rods, both graphite and glass, you’ll want a selection of 27-to-30-foot shooting heads in different sink rates, from a slow intermediate all the way to T-14 tungsten or straight lead core. For the two-handers, it’s still a bit of a zoo out there, with scores of fly-line choices and as many opinions about them as there are fly patterns, but it’s become easier as rod and line manufacturers have worked together to delineate suggested tapers and grain-weight windows. I’d start with one of the longish “midSpeys” with interchangeable tips for the 13-footer and a short Skagit head with a selection of sinking tips that’s matched to the big 14-footer.

Whatever your choice of rod and line — and a good fly shop can be of immense help here — learning traditional Spey techniques before you get hooked on Skagit or Scandi is a wise move. A firm grounding in the basics will pay off in the long run, no matter how you fish. The same thing goes for learning to cast shooting heads with a single-handed rod: master the basics with a floating line first, and you’ll do better and do so sooner when you start fooling with shooting heads and mono running lines.

Many fly shops offer casting classes, including classes for double-handed casting. You can also improve your casting skills through clinics put on by a variety of casting gurus, or through your local flyfishing club. San Francisco’s Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club, host to the Jimmy Green International Spey-O-Rama, the World Championship of Spey Casting, hosts some very good clinics.

Recent New Stuff

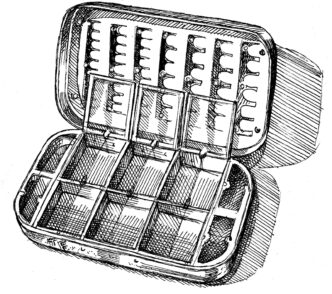

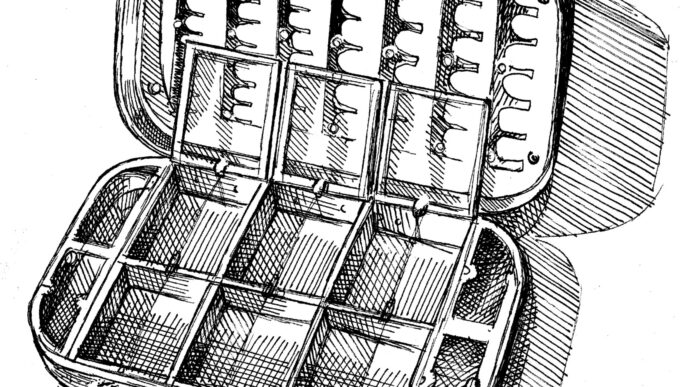

Carrying the right flies while on the water presents a challenge to the fanatical trout angler. Multiple boxes are clearly the solution, but many new boxes are so large that it’s tough to fit more than a couple in a vest or fishing pack. One solution, for nymphs, spinners, and mergers and for some streamers, at least, is the new Ultra Slim Fly Box by Angler’s Image. At 7-3/8 inches by 3-7/8 inches and just half an inch thick, it comes in two versions: one with 168 foam slots for small flies and another with 30 slots that are just big enough for medium-size buggers and streamers. Because they’re only half an inch thick, I can fit three of either model in a vest pocket that used to fit just one thicker box. Not only do you get large capacity, the individual boxes let you organize flies in multiple ways: one box, say, for PMD nymphs and emergers, another for midges, or Baetis patterns, or caddis imitations, or flies for a particular river or season . . . you get the picture. The boxes have a clear lid so you can see what’s inside, and they close securely. The retail price is $12.50.

Where Angler’s Image chose a minimalist approach to fly storage, Umpqua Feather Merchants has taken a more varied one. Their new, double-sided UPG boxes are available in eight configurations, each of which has two fly trays under clear plastic lids. (“UPG,” by the way, is an acronym for “Umpqua Professional Guide.”) Flies are captured either in micro-slit foam or against magnetic plates, or a combination of both. The boxes are water resistant and the plastic is enhanced by Zerust Corrosion Protection which releases rust-inhibiting vapors. By using lids of different depths, widths and heights, in combination with different foam/magnetic inserts, UPGs provide a variety of configurations and the necessary headroom for just about any type or selection of fly, from midges to flats flies to streamers. Available in a handful of cool colors, your organizing possibilities are, if not limitless, then at least more numerous than my math-challenged brain can compute. Prices range from $24.99 to $42.99. Visit Umpqua’s www.flyboxevolution.com for more information.

RIO has recently developed a line that should be welcomed by stillwater anglers. The RIO Camolux line is a clear intermediate weight-forward line with numerous subtle color changes (reds, blues, and clears) that blend in with varieties of surface and water conditions. Available in weight-forward tapers from 3-weight to 8-weight, the lines have a sink rate of between 1.5 to 2 inches per second, a supple core, and a slick, coldwater finish. Front tapers look to be longish, thereby enhancing stealthy presentations.

Echo’s new Ion large-arbor reel is another interesting entry into sub-$100 discdrag reel category. Made from cast aluminum that is machined to final dimensions, the idea, according to distributor Rajeff Sports, is to provide the tolerances and benefits of a machined bar-stock reel without the high price associated with full machining. Ions features a friction cork disc drag with an outgoing click, ballbearing smoothness of operation, and a matte-black finish. The reel is available in four sizes, from a 3.4-inch-diameter 4/5weight trout reel to a 4.7-inch model that will handle most fly lines for double-handed rods. Prices are $79.99 for the two smaller sizes and $99.99 for the two larger sizes. An optional oversized drag knob made from solid brass is available for the two larger models, adds 2.3 ounces to the reel’s weight, and helps balance longer two-handed rods ($15.99, sold separately).