Technical advances are frequently driven by some tinkerer’s dissatisfaction with what’s already available. That’s certainly been true with fly rods, and Californians have long been at the forefront among those who have tried to improve the long rod. In the popular distance-casting competitions of the early and mid-twentieth century, for example, split bamboo as a rod-building material had hit a wall. A rod maker could achieve more power and casting distance by putting more wood in the rod, but the rules prescribed a maximum weight.

E. C. Powell, in Marysville, a tournament caster himself, changed the game when he figured out how to hollow out his bamboo rods selectively by laminating just the dense outer power fibers of a bamboo strip to lightweight cedar, cutting the laminated strips to the right tapers, then routering away some of the cedar from the finished strips before gluing them into a blank. The remaining cedar provided enough surface for glue, and the hollowed areas significantly reduced rod weight. The result was Patent No. 193298 of 1933 and light, powerful fly rods that were winners not only on tournament ponds, but also on big Western rivers. Five years later, in San Francisco, R. L. Winston’s Lew Stoner addressed the same issue and patented another way to reduce rod weight by taking a hollow cut along the length of the inner apex of individual bamboo strips in fly-rod butt sections. That removed most of the weight of those inner fibers while still leaving a surface for glue and gave birth to Winston’s own renowned fluted, semihollow rods.

In the development of composite tubular rods, Californians Jon Tarantino and Jimmy Green were not only significant innovators in blank design, but came up with, respectively, the internal spigot and tip-over-butt ferrule designs that took stiff, heavy metal ferrules out of the game. Green was also in the vanguard of rod designers who saw the benefits of carbon fiber, and his Fenwick HMGs led the graphite charge of the mid-1970s.

Another Californian — by preference and residence, if not by birth — with unique takes on fly tackle was my friend Harry Wilson, the founder of the Scott Fly Rod Company. I don’t mean to suggest that Harry’s contributions were in the same league as those of Powell, Stoner, Tarentino, or Green. But he’s still well worth noting as another link in the chain of California’s fly tackle innovators.

Harry was born South Dakota in 1912 and spent his boyhood in rural Idaho. He fished as a boy, but from what he told me, he was more a tinkerer, fascinated with projects such as rebuilding the old Model T he’d acquired. That technical bent sent him to college, first at Cal Tech and then, when the Depression hit, to the University of Chicago, where I believe he got a scholarship that took the financial load off his parents.

At Chicago, he studied business administration and earned an MBA when that degree was relatively rare. He met and married his college sweetheart, Betty, there, with whom he raised a son and a daughter. A successful career in marketing followed with a number of firms in the Midwest, including work with A. C. Nielsen, a visionary firm now known best for its television rating service. A subsequent position with Butler Manufacturing in the 1950s sent him to Australia, where he worked on developing metal building systems.

Harry left his last “company” job at Aerojet on the Monterey Peninsula in the late 1960s to start his own consulting firm in San Francisco. My sense is that the move to San Francisco was made as much to be close to Northern California fishing as for business reasons, and Harry soon became hooked on surf stripers, fall kings, and winter steelhead. The Bay Area fly-fishing community, particularly the friends he made through the San Jose Flycasters, changed Harry from a dedicated lure fisherman into an even more dedicated fly fisher. His lifelong predilection for tinkering led him to fooling with and trying to improve fly tackle.

I first ran into Harry at the old T&S Tackle shop on Valencia Street in San Francisco in 1971, when I was in grad school at Cal. Bill Chapelle, the owner, loved to gab and would frequently invite customers to join him in the back of the shop for a cup of coffee. On one of those visits, I asked Bill what he could tell me about fly fishing for striped bass. He said he couldn’t be of much help, but knew a guy who might.

Harry, it turned out, was using the turret lathe that Bill had in a little back alcove to build a fly reel and was doing some fly fishing for stripers in San Francisco Bay. Bill told me when Harry was likely going to be around, and I made it a point to stop by. We talked about stripers some, but I recall that we mostly talked about fishing on the Eel and the Russian and about the fly rods and reels he was building.

He’d had his knuckles rapped pretty hard by the handle on a Pfleuger Medalist when a salmon he was trying to net made an eleventh-hour lunge. He wanted something better. There weren’t many antireverse or disc-drag reels available for anything other than big bucks back then, so Harry figured he’d make one of his own. A hobby woodworker, but not a machinist, he took a night-school course so he could use Chapelle’s lathe to cut the parts. That reel project would of course end up being far more expensive than buying the priciest Seamaster, but Harry was having fun. He also thought he saw an opportunity to build and sell the reel design that was rattling around in his head.

Harry turned out a few direct-drive disc-drag reels, but his main interest was a unique antireverse model he’d thought up. You set the drag with a knob in the center of the crank side of the spool to whatever resistance you wanted, but by backing off a quarter turn or so on the handle, you reduced drag resistance by about half. A quarter turn forward brought the drag back up to the maximum you’d set earlier. That system let you work a fish to net or shore with your hand on the crank taking up line while being able reduce drag quickly without letting go of the crank: nice for those last-minute runs, when the fish spooks off the boat or the net.

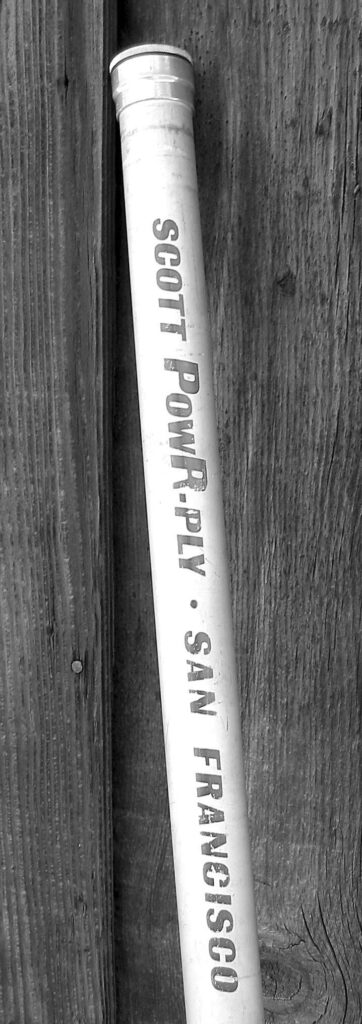

That reel, to Harry’s way of thinking, applied power through the drag system, so he called it the Scott PowR-ply reel, named for his son Scott and the unique drag. He eventually got a patent for the design, but for reasons I’ll get to shortly, the reel never made it to market. I think he made eight or ten reels in all, some of them direct drive models, some of them the antireverse model, all of which ended up with friends. While working on his reels at T&S, Harry also began building rods there, first for his own use, then for angling friends. I bought two over the course of a couple of years: a little 7-foot 4-weight that I wish I still had and a 9-foot 10-weight that’s seen service on everything from San Francisco Bay striped bass to Baja yellowtails. Workspace in T&S’s back rooms was limited, and Bill Chapelle’s sociability got on Harry’s workaholic nerves. He ended up putting together some workbenches and a cork-turning lathe in the garage at his home on Tenth Avenue, where he built rods until late 1974. Word-of-mouth demand soon had him building rods for sale under the Scott PowR-ply name. A neighbor who was the assistant manager at the new Eddie Bauer store on Kearney Street liked what he saw and put some of Harry’s rods in there. Abercrombie & Fitch in San Francisco did so, as well, and they were soon joined by a few fly shops, such as the old Fly Hutch in Cupertino.

Harry’s early fly rods were built on standard yellow Lamiglas blanks that he fitted with internal “spigot” ferrules in his basement shop. Those ferrules differed from the Tarantino/Merrick internal ferrules in that Harry’s were made f rom stacked glass tubing and were semihollow, rather than solid. “Semihollow” meant that the ferrule wall was almost solid for half an inch or so on either side of where it protruded from the butt section, then tapered to a relatively thin wall at the tip of the ferrule and at its base inside the butt. Harry saw this as a way to build a strong ferrule while also saving weight and minimizing the potential for a double wall-fracture point at either end of the spigot. Unlike the tip-over-butt ferrules made popular by Fenwick, it also allowed for continuous diameters across sections to help maintain smooth power flow up the rod.

By late 1972, Harry had about half a dozen glass models worked out, from short 4-weights to heavy 10-weights and 11-weights. They were mostly two-piece, but a few of the lighter ones were four-piece rods. What was unique about Harry’s rods, apart from the ferrules, was his use of additional internally tapered fiberglass tubes, made from the same hollow glass material as the rods and ferrules, that were epoxied at specific points inside the tips and butts of two-piece models. Their function was to add stiffness or mass at particular points in order to fine-tune rod action. Those “sleeves,” as he called them, made a noticeable difference and became a hallmark of Scott’s California-built glass rods. I see inklings of this idea in the writing of folks such as George Leonard Herter, but Harry thought of it independently and was the first to make something of it commercially.

Never an easy man to deal with, Harry wasn’t happy working with Lamiglas and ended up shifting his source of rod blanks to the California Tackle Company in Southern California, the outfit that made the popular Sabre conventional rods. By that time — 1973 or so — Harry had become intrigued with lightline fly rods. Cal Tackle had just one fly-rod mandrel taper, workable only for 6-weight and 7weight lines, so Harry designed a slower, smaller-diameter, compound-taper mandrel for use only on his Scott PowR-ply lightline rods. Those rods, for 3weight, 4-weight, and 5-weight lines from 6 to 8-1/2 feet in length, were particularly sweet casters and today are much sought after by anglers and collectors. I think of his five-piece 7-foot 4-weight, developed in 1973–74, as the Holy Grail of collectible Scotts. I doubt there were more than 100 or so ever built.

Rolled from an e-glass–polyethylene resin prepreg and overwrapped before curing with a particularly tough, high-tension shrink tape, Scott blanks made by Cal Tackle (first in yellow, later in brown glass) were only very lightly sanded after the shrink tape was removed, then were dip-coated with a clear finish. Harry felt — and it was certainly true back then with Cal Tackle — that sanding was an imprecise operation that resulted in uncontrollable variation between blanks. By just barely sanding a blank, leaving most of the ridges from the shrink tape, Harry figured that the glass he designed into the rod stayed where he wanted it.

In addition to e-glass trout, steelhead, and light saltwater fly rods, Harry also experimented, as early as 1972, with glass blanks for 12-to-15-weight lines. He loaned a few of the prototypes to his friend Bob Nauheim to use on Costa Rican tarpon, and Bob’s favorable reports were another nice boost to the growth of what became the Scott PowR-Ply Company.

I was teaching part time at De Anza College in the early 1970s, but fished and spent a good deal of time with Harry, who had retired from consulting work. The end result of that connection was him talking me into joining him in late 1974 in making Scott a serious business. Our original plan was to use the rod business to make enough money to produce Harry’s fly reel. We had a small group of investors, including me, Bill Chapelle (whose turret lathe was his buy-in), and half a dozen other family members and friends, and we incorporated under the name Scott PowRPly Company, Inc.

Harry’s garage was tiny, so we rented a small street-level space — originally a residence — on Cook Street, just off Geary Boulevard in San Francisco, as our workshop. Bill Schaadt, a friend of Harry’s, painted the sign we put up next to the door. We cut and ferruled and wrapped rods in the large, high ceilinged-kitchen, corked and turned handles in one small bedroom, shipped out of another, used the tiny living room as an office, and test-cast rods on the sidewalk outside when we didn’t want to make the trip out to the Golden Gate Park casting ponds. We taught two high school kids to wrap guides, and they came in after school. Harry took the wrapped rods home to his basement to coat the wraps. I built fly rods during the day and commuted to Cupertino to teach four nights a week.

Fortunately for us, the company’s entry into the rod market coincided with two significant shifts in the fly-fishing world: the rise of the independent fly shop and the emergence of graphite as a rod-building material. Without the small fly shops that started cropping up all over the country in the late 1970s, Scott would not have been possible. With those shops as outlets looking for good gear to sell, we grew the company steadily from the Bay Area north into Oregon and Washington, south into Southern California, east into the Rockies (Dan Bailey was an early dealer), to a few shops on the East Coast, and to Europe and Japan. We built and sold an increasing number of glass fly-rod models until 1981, when a series of ownership and machinery changes at Cal Tackle resulted in blanks that we felt were unacceptable. We continued to build glass rods on the remaining inventory for a handful of years, but by 1981, graphite had become what the market wanted, and that’s where our efforts went.

Prior to the mid-1970s, short rods were all the rage, and long rods were rarely built for lines lighter than 6-weight or 7-weight. Graphite changed that. By 1975, Harry was already fiddling with some very early graphite blanks built by J. Kennedy Fisher, and later that year, he put together a couple of prototype 9-foot graphite rods, using metal ferrules. While light, they weren’t very exciting, but Harry recognized the material’s potential and focused our development energy on long, light-line graphite rods: something the material could do easily that fiberglass and bamboo couldn’t.

I believe Fenwick was first off the mark in this area, with its long HMG905, but Harry and Scott weren’t very far behind. Working with Fisher’s mandrels, he designed graphite patterns to create lighter tips and somewhat stiffer butts and connected them with a graphite version of Scott’s hollow internal ferrule. The result was the Scott G904 in 1976, followed closely by the G906. Both sold well, but at first only with the small number of adventurous anglers who were willing to try something different.

Like our glass, those first graphites were semi sanded, but we soon went to completely unsanded blanks with relatively Spartan fittings. Cosmetics, for Harry, were secondary to performance. But those first graphite rods were casting and fishing fools that ended up selling faster than we could build them. It wasn’t until the mid1980s that I and a few others could talk Harry into bringing Scott fly rods up to a higher level of appearance, though we still took flack for the unsanded blanks.

Harry’s fly reel, by this time, was on a far back burner and ultimately was never resurrected. CNC machining had yet to be developed, the reel was costly to make, and the market was small. We concentrated on graphite rods, which looked like they had a future.

In 1977, Harry decided that while Fisher’s straight-taper tip mandrels were OK, we could improve performance with a compound-taper tip like that in our light-line glass rods. He had a set of new mandrels fabricated for use on just our rods, and they made a considerable difference in short-line finesse. We used them with Fisher’s factory butt mandrels and with various 30-million-modulus graphite patterns of our own design on all our long trout rods. It amuses me to recall that many anglers back then were not only uncomfortable with 9-foot trout rods, but felt that Scott’s early graphites were way too fast. Today, a 9-foot rod is the default length for most trout rods, and when you can find an old G906 or G904 on the used market, it’s billed as a soft-action rod.

The fiberglass blanks that Cal Tackle fabricated in the 1970s had been extremely consistent, which is to say, blanks of a given model flexed and weighed the same, run after run. We assumed that was going to be the case with graphite, but found to our distress that there was considerable variation in blanks rolled on the same mandrels with the same flag pattern. Much trial casting and testing revealed that the variation originated in an uneven distribution of graphite fibers combed across the standard 12-inch-wide prepreg tapes. That meant that a pattern cut from one side of the tape or at one point on a roll of tape might be as much as 10 percent lighter or stronger than those cut from somewhere else on the same roll. The result was tips or butts that were different when they should have been identical. That variation drove us nuts until we figured out how to make productive use of it through a rating system that measured the resistance to bending of a particular tip or butt.

Knowing how strong a section was let us match tips on the lighter end of that spectrum to butts on the lighter end and heavier tips to heavier butts. Blanks that were too stiff or too light for a given line weight and model were discarded. Harry called the system “flex-rating” and using it gave us exceptional consistency of rod action within a given model. It also let a customer choose, for example, a 5-weight rod that was closer to a 6-weight or one that was closer to a 4-weight.

In 1980, we’d outgrown our little shop on Cook Street and moved to a larger space on Clementina Street, an alley south of Market Street in San Francisco. With room to spread out a bit, we hired a few more rod builders to handle increased production and developed multiple new models, including some of the first multipiece graphites. The 1980s were heady days in the rod business, and Scott, like most other fly tackle companies, was growing by double digits every year. In 1986, when San Francisco rents became too expensive, we moved the company to the first of three successively larger spaces in Berkeley.

Harry had an eventful 15 years designing rods, working on new models, and expanding the Scott PowR-Ply Company into a stronger presence in the fly-rod world than our tiny operation might have been expected to occupy. During those years, he traveled widely across the United States and to Japan, New Zealand, and Australia, showing the Scott flag and fishing a good deal, though I suspect he frequently preferred talking. For Harry, who could no more stop working and talking about fly rods than stop breathing, planting Scott firmly in the fly-fishing firmament was the crowning achievement of a long career. There aren’t many folks in their early sixties who start and grow a successful business. I remember him chuckling, on his sixty-fifth birthday, that “the retirement bastards haven’t got me yet.”

In 1987, however, after what was supposed to be a relatively routine surgery, Harry suffered a debilitating stroke. Rehab was only moderately successful, and his physical condition kept him from active participation in the business. Fortunately, by that time, Scott not only had a great team, but we’d already begun the process of finding a buyer who could provide the kind of outside capital needed to take Scott further. In 1988, William Clay Ford, Jr., of the Ford Motor Company Fords, purchased Harry’s majority interest in the company, along with that of all the other stockholders but me. I stayed around for another half a dozen years, by which time the Scott Fly Rod Company, as it was now named, had moved to and become firmly entrenched in Colorado.

To say that I’m proud and happy to have been Harry’s friend and colleague and to have been a part of a remarkable man’s notable achievements is an understatement. Harry died in April of 1995, and his family scattered his ashes on a favorite steelhead river. The Scott Fly Rod Company continues to thrive in Colorado.