Last issue’s “Gearhead” covered only some of the components that go into turning a blank into a rod. I’ll continue in this issue with a look at the choices available in blank finishes, hardware from the tip top down to the grip, wraps and wrap finishes, and rod tubes and cases. Both columns together will give you a thorough idea of the choices that go into constructing a fly rod.

Blank Finishes

Although it’s not properly speaking a component, let’s start with the surface finish on the rod blank, since it’s applied, or isn’t, after the blank has been rolled and thus represents both a manufacturing choice and an option for the rod builder or purchaser. The alternatives are sanded smooth (sometimes called “natural”) blanks, unsanded blanks (on which the footprint of ridges from the shrink tape used in curing the blank remain in place), or painted blanks that are either dull/matte or shiny. Arguments against sanding are that it risks damaging the blank and removing material the designer wants included. Arguments for sanding are cosmetic: smooth looks better. Opinions used to be strong on either side, but I think we can be pretty certain that if sanding damaged blanks, the great majority of rods on the market wouldn’t be sanded.

How about blank color? One skeptical fly fisher I know dove in some trout streams and looked up at what the trout were seeing. His conclusion was that the most visible rods are dark in color, while light-colored rods, or, better still, those with a broken finish of light and dark, show up far less. I don’t know of many rods with light-colored blanks, and none with camo finishes, but a few manufacturers make matte-finish rods, and there are still some with “natural” finishes that aren’t glossy. Again, were this a highly critical issue, nobody would be taking spooky fish on the shiny, dark-colored rods that dominate the market, and we know that isn’t the case. And of course, the fish still see something, no matter whether a rod is light or dark, or shiny or dull. Still, it’s worth thinking about if you’re a stealth fanatic. You pays your money and you takes your choice.

Tip Tops, Guides, and Hook Keepers

From the tip of the rod down to the grip, the hardware includes tip tops, regular guides and stripper guides, and hook keepers. Traditional tip tops — the round thing at the very tip of a fly rod — incorporate a wire bent to a teardrop shape, attached to a tube that goes over the tip of the blank. In the past, the finish on the entire top tended to be softer than the finish on the snake guides below it, due in part to soft metals in the loop and to plating or painting that didn’t provide a hard surface. Today’s tip tops have loops of high-carbon or stainless steel and are plated with hard chrome or other very smooth, tough finishes. Hard though they are, it’s still worth checking them occasionally for wear. That’s particularly the case if you fish heavy shooting heads and the tip top gets a lot of pressure from the sawing action of multiple line hauls with mono or small-diameter shooting lines. Unlike the other guides on a rod, a tip top is generally held in place with a heat-sensitive glue and is easy to remove and replace.

When it comes to guide choice for fly rods, you have to navigate a maze of options. Let’s start with the easy stuff. How many guides should there be? For the rod maker, using fewer guides represents less material expense and, perhaps more critically, less wrapping and finishing labor. But if you use too few, they don’t adequately distribute the load when the rod is bent, and you lose distance when the line slaps against the rod on the cast. The general rule of thumb is that apart from the tip top, a good rod will have as many guides as its length in feet and one or perhaps two more, depending on how the section breaks fall.

The guides below the tip, except for those closest to the grip and reel seat, are usually “snake” guides, named for the spiral way a piece of wire is bent to form the guide. Snake guides usually decrease both in size and in the diameter of the wire used to form them as they approach the tip.

Compared with what was used in the past, the current trend has been to use rather large snake guides, particularly with rods for 7-weight lines or heavier. The idea here is that a line shoots more easily through a large guide and that a bulky knot will be less likely to snag. The downside of large snakes is weight out toward the tip, though the rod designer will take that into account. I’m still not convinced about improved shooting ease with oversize snakes, and knots can catch in the crotch formed by the wire and the rod blank, even if the guide is large. I’m similarly unconvinced by arguments that relatively small guides aid shooting by minimizing the space in which a line can slap against the blank during a cast. As with many things, the sensible option is to try to avoid excess. You really don’t need size 4 snakes on the outer tip of a 6-weight trout rod, but you probably don’t want anything smaller than a size 4 anywhere on a 12-weight.

How about traditional snake guides versus round/single-foot ones? Tim Rajeff told me that he thought he’d originated the single-foot snake while he was at G. Loomis, but discovered that the idea had been patented in the 1890s. Traditionalists dislike them because they’re . . . well, not traditional. Some manufacturers love them because there’s only one guide foot to wrap and coat. My experience is that neither style has a real advantage over the other when it comes to performance. Single-foot advocates claim they shoot better, though I’ve never been able to confirm that. By avoiding the crotch between wire and blank of traditional snakes, single-foots may lessen the likelihood of a knot hanging up and may keep the line from slowing also be a bit lighter, if the length of wire used is shorter. Potatoes, putaahtoes. The same goes for British versus American style snake guides: one bends to the left, one to the right. Both work the same.

How about hardness? Old-time snake guides were bronze or a bronze that was painted black. Though they’re still sought after by traditionalists, bronze is soft, and the guides wore easily. Steel snakes with a chrome finish were a significant improvement, but were superseded when stainless steel guides electroplated with harder and thicker “industrial” chrome finishes became available in the 1970s. Contemporary snake guides can be given even harder finishes with the wire getting a coating of titanium or nickel via vapor deposit.

Recoil brand snake guides were developed by REC some years ago. Made from a titanium nickel alloy, they’re also expensive, but they spring back to their original shape when bent, a nice feature if you bang your rod around a lot. However, in low temperatures, below freezing, for example, the alloy behaves like any other metal and stays put when bent.

Single-foot or double-foot, chrome, titanium, or Recoil, they all work fine, and we can be grateful that they’re all harder and slicker than ever. But unless you’re fishing in glacial silt, industrial hard chrome is probably more than sufficient. The new finishes do represent the cutting edge in snake guide design, and many makers feel that’s what’s appropriate on their top-end rods. And of course, there’s the shininess issue. Duller-surfaced hard finishes may well offer an advantage when casting to spooky fish.

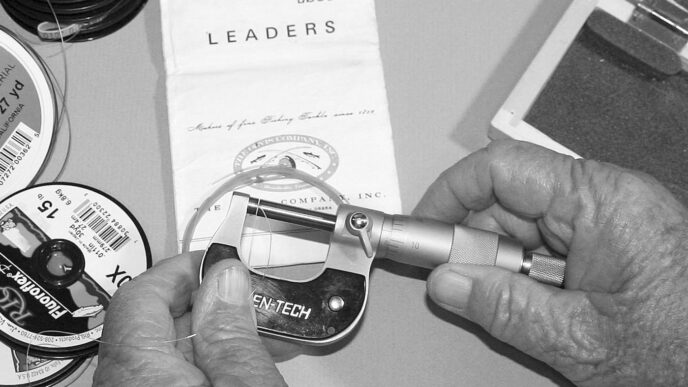

The nearest guide to the grip on a rod will be one or sometimes two of the kind where a ring of some sort is fixed in a separate frame. Fly fishers call them “stripping guides,” though bait casters and spin casters simply call them “guides.” Their function is to capture the fly line smoothly as it comes off the hand (or ground, or deck, or line management device). Forty years ago, expensive rods used either polished agate set into a metal ring or a ring of a tungsten-nickel alloy (such as “Carbaloy”), both of which were soldered or spot-welded into a frame of nickel-silver wire. Less expensive rods used some form of plated-chrome ring guides. Chrome is not as hard as either agate or Carbaloy, but the hard-chrome variety sold by the now defunct Perfection Tip Company was less expensive and functionally as good as anything on the market. Variations of that guide are still used on many conventional rods, and that wouldn’t happen if they wore badly. Agate and Carbaloy guides are also still around and much in favor with bamboo rod makers.

Stripping guides were also smaller back in the day, with internal ring diameters of 6 to 10 millimeters, even on steelhead and saltwater rods. Contemporary practice is to use large stripping guides. It’s rare to find an 8-millimeter guide on even a very light-line rod these days, and you’ll never see a 6. Twelve-millimeter stripping guides are more the norm, even on trout rods, and big rods see a lot 20s. The idea is that big guides capture line better, but I wonder if we haven’t pushed this to extremes. My tests don’t show much difference in distance or how much line I can shoot between a rod with a 16-millimeter stripper and one with a 20 or one with a 12-millimeter stripper and another with a 16. That noted, were small guides as effective in clearing line on distance casts, tournament casters would use them, and they don’t: the shooting-head distance-casting event with what’s essentially a steelhead rod sees rods fitted with 20s and 16s.

How about the value of multiple stripping guides? Older rods tended to have a couple and sometimes three or four in declining sizes. I suspect the idea was that stripping guides keep the line farther away from the blank and handle heavy lifting better. Lately, we see two strippers only on medium-to-heavy-line rods, probably under the assumption that a second stripper gathers line better than even a large snake. I’m not sure that’s true, but a rod with two strippers does seem to look right. Contemporary stripping guides have metal frames into which are spot-welded an outer metal ring that captures an inner ring made from one very hard ceramic substance or another. Frames and outer metal rings are anodized, chrome plated, or, in some cases, coated with a substance such as titanium oxide using a vapor-deposit process. The ultimate hardness and slickness of the ceramic ring is a function both of the quality of the ceramic used and of the amount of polish the ring is given.

Rings, too, are occasionally vapor-coated with hardening agents.

The hardest, most expensive stripping guides will cost many times the cost of all stainless steel guides. What’s the gain from using them? Weight is one consideration; contemporary high-tech strippers can be half the weight of older style guides. Slickness and hardness are another consideration, though I think this is less significant for most fly rods than for blue-water rods, where guides take the load of heavy fish on thin Dacron backing or tough braid. Truth be told, an inexpensive ceramic ring that’s been highly polished and vapor-coated with titanium is probably just as hard and slick as a more expensive ring that hasn’t had that sort of attention. And once again, hard-chrome stainless guides, while a bit heavier than fancy ceramics, are pretty much bulletproof.

What is the weight difference? I weighed five different size 10 strippers on a digital scale to find out. The Carbaloy guide weighed the most, at 1.1 grams, and the Recoil stripper and the Fuji titanium frame stripper weighted the least, at 0.5 grams. A chrome-framed stripper with an agate insert came in at 0.9 grams, while a Hopkins & Holloway hard-chrome-frame ceramic stripper (an industry standard) and an older, plain hard-chrome stainless stripper both weighed 1.0 grams. A finished rod using the lightest versus the heaviest of those guides would be about .02 ounces lighter. That’s two one-hundredths of an ounce, not two-tenths. Perhaps that princess who couldn’t sleep on 20 mattresses when there was a pea them would notice that. I doubt the rest of us could.

The revelation here is that an inexpensive ring, highly polished and vapor coated with titanium, is as hard and slick as a more expensive ring costing the manufacturer much more. And hard-chrome stainless guides, while perhaps a bit heavier than fancy ceramics, are pretty much bulletproof.

Appearance and angler perception also play a role in guide choice. The new strippers are techy looking, and we’ve become a techy bunch. And of course, when you’re buying an expensive fly rod, you like to think that only the best components are included. Still, were I building a fly rod, even for big fish, I’d concentrate on the blank, the reel seat, and the cork and not worry too much about what super-expensive guides were going to do for me.

Hook keepers are generally wrapped just above the cork grip. A dozen kinds are available, from a simple U formed in wire to little gizmos with springs. If you like them or think you need them, you’ll probably be unhappy with a rod that doesn’t have one. I think they’re at best a waste of wire and wrapping thread and at worst insidious little devices just waiting to cut a slice from my hand when it slips forward off the grip. Not that I’m prejudiced . . . .

Guide Wraps and Finishes

What about guide wraps? Nylon thread in size A is the standard, except among hard-core bamboo aficionados, who favor silk and like the smaller-diameter 00 thread. Wraps add no structural strength to a rolled blank, so a long wrap isn’t necessary. Covering the guide foot thoroughly is all that’s needed. A secondary color at the tip or center of the wrap is nice, but purely cosmetic — or a way for a rod maker to demonstrate skill. Sometimes the most handsome rods are monochromatic. And of course, wrapping and coating errors are less visible when the thread and the blank are the same color.

Guide wraps are generally coated with a one-coat or two-coat epoxy finish as the rod turns on a revolving fixture until the epoxy sets up. Obviously, the fewer times the maker needs to apply finish, the less money he spends, and the rod can go out the door more quickly. But single-coat finishes tend to be pretty thick, and they tend to pull away from the edge of a wrap and bulk up a bit in the middle. That’s why you see the finish extend well past the wrap on most contemporary rods. On rods from the 1970s and earlier, only the thread was coated, with multiple coats of a thinned varnish or polyurethane, and the resulting look was flatter. I like the look of the old, flatter finish, but the new epoxies are much tougher and don’t fade after exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Whatever the finish, it should be without bubbles, with an even cross section and clean edges.

Rod Tubes and Cases

Finally, fly rods generally come in a rod case of some sort, with a partitioned cloth sack to keep the rod from getting scratched. Aluminum used to be the standard for rod tubes, and it still is for most expensive rods. But for overall rod protection, nylon-covered plastic tubing is just as good and is certainly less expensive. For the angler who has a lot of fly rods (and I stopped counting when the total got to 20), storing rods in individual tubes aids in knowing what you’ve got, though I’ve found it makes sense to add a highly visible label if one’s not already there. For traveling, however, a large-diameter case that holds a bunch of rods in their cloth sacks is a good idea. And if you’re in a boat or travel a bunch with a rod already rigged, one of the nylon-covered cases with a padded section for a reel is a terrific help.

Don’t Worry — Go Fishing

Fly rods and their components are clearly a tackle category that can be overthought. The ugly and delightful truth is that today, unlike the past, there are very few bad rods or unworkable components. That doesn’t prevent any of us from having strong opinions or finding choices that work better than others, but spending time on the water is the real answer to most fishing problems.