What’s the Deal with Tube Flies?

Tube flies originated in Europe on metal tubes in the mid-20th century and gained popularity in North America among Pacific Northwest salmon and steelhead anglers during the 1980s. Although they’ve been around for decades, I seldom see other anglers fishing tubes. Even on social media, it’s uncommon to come across more than a handful of accounts posting tubes, and those are usually from Scandinavian or Icelandic tyers. While tubes might not be a revolution in fly tying, they’re a solid tool to add to your kit—one with genuine advantages, a few quirks, and a small learning curve.

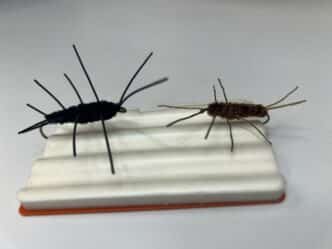

If you’ve never tied on tubes, picture this: instead of winding materials directly onto a hook shank, you build your fly on a short plastic or metal tube. Your leader passes through the tube, and you tie your hook to the end of the line. When a fish eats, the fly slides up the leader, away from the fish’s mouth.

It’s a simple concept that solves a few problems—but, like many fishing solutions, it also creates a few problems of its own. I’ll do my best to outline the pros and cons, though my bias will be hard to mask: I think tubes are darn fun to tie, offer a novelty to fish, and allow creativity in ways that shanked flies can’t.

Why Tube Flies Deserve a Spot in Your Box (or Pocket)

BETTER HOOKUPS & HOOK RETENTION

Ask any steelheader or salmon angler why they love tube flies, and you’ll probably hear about hookup rates. With the body of the fly tied on the tube, you can use a short-shank hook, giving big fish less leverage to shake it loose. Because the hook detaches from the fly body, it can pivot freely, reducing torque when a fish thrashes. The theory is the same as with other trailing hook patterns, such as Intruder-style flies: The trailing hook reduces leverage and improves hook retention.

In theory, this means more landed fish and fewer heartbreaking headshakes. In practice, it’s not a magic bullet—but it does stack the odds slightly more in your favor, especially with larger, harder-fighting species.

MODULAR CREATIVITY

One of the underrated pleasures of tube flies is their modular design. You can tie separate wings, bodies, and tails—each on its own mini tube—and then stack them to create multi-stage or color-blended patterns.

This approach allows you to build combos on the water: a black-and-blue wing for overcast mornings, a chartreuse body for stained water, or a two-stage pattern with contrasting flash.

Some credit this modular stacking technique to Tony Pagliei, but I first saw it done by April Vokey, tying a multi-section Intruder for steelhead. Whoever came up with it, it’s brilliant. You’re no longer locked into a single look in the field—you can mix and match like Lego for fly tyers.

HOOK FREEDOM

Because the hook isn’t married to the fly, you can swap it out whenever you want. If a hook dulls, replace it. If you’re switching from Dolly Varden to coho, size up.

You can also orient your hook point up to avoid snags—a small change that makes a big difference when swinging through woody runs or mossy rocks. Granted, you might need to tweak the weight and wing of your pattern to ensure it still rides correctly, but the flexibility is there.

Smaller hooks also mean gentler releases. Since the fly itself stays out of the fish’s mouth, tube flies usually cause less harm and last longer.

POCKET-SAFE

Imagine it’s 36 degrees in February on the Olympic Peninsula, the rain beats down, and every gust of wind is stronger than the last. Your fly box is in the boat at the top of the run. Why didn’t you just throw a few rotation flies into your jacket? Right, because you didn’t want to impale a frozen finger digging around in your wet pocket or put a hole through your $500 Gore-Tex jacket. Fish in these conditions long enough and we all get lazy. With the hooks stored separately, you can toss a handful of tubes into a pocket or Ziplock without risking acupuncture.

DURABILITY THAT PAYS OFF

Because tube flies slide up the leader during the fight, they take far less abuse. The hook takes the beating, not the fly. This results in less frayed material, fewer destroyed heads, and flies that can last through multiple seasons. With many small-batch flies running $15 or more these days, that’s a significant advantage.

THE FUN FACTOR

As I mentioned earlier, tying on tubes is just plain fun. The first time you see your fly slide up the leader, it’s satisfying in a way only anglers understand.

And at the vise, it feels novel. You’re working with different materials and pushing your creativity by tying old patterns on a new medium. There’s no need to switch over completely, but experimenting with tubes will make you a better tyer overall.

The Tradeoffs

RIGGING HASSLES

Candidly, I’m lazy—or more self-respectingly put, efficient—so this is my number one. When you and your fingers are cold and wet, the last thing you want is to add an extra step to changing your fly. Threading a leader through a plastic tube is exactly that, and you’ll need to carefully measure how far back your hook trails from the head of your knot (unless you use a simple hook guide). Add to that the fact that dry marabou from a fly fresh out of the box loves to stick to wet fingers and get in the way of your knot. Re-rigging a tube fly in freezing conditions can be tricky. (Pro tip: Dunking the fly underwater will tame the materials, making the rigging quicker but your fingers colder)

It’s an extra step that can be annoying, especially if you like to switch flies frequently.

BRAND COMPATIBILITY (OR LACK THEREOF)

Not all tubes, junctions, and cones play nice together. One brand’s connector tubing might fit snugly on their own poly tubes, but slide off another brand’s.

For example, Pro Sport Fisher’s weight system integrates perfectly with their tubes but doesn’t always fit others. It’s a bit like trying to use an iPhone charger on an Android. If you’re buying components, stick to one brand until you’re comfortable. Later, you can mix and match once you know what fits.

THE PLASTIC PROBLEM

This one’s worth acknowledging. Many tube flies use some form of plastic tubing, and even if you’re tying on metal tubing, chances are your flashy materials aren’t biodegradable. Lose a fly—plastic or not—and it ends up somewhere it shouldn’t. If you’re tying and fishing a lot, metal tubes are an alternative, though they’re heavier to cast on big flies, sink faster, and cost more.

THE LEARNING CURVE

If you’re used to tying on hooks, tubes will feel weird at first. You’ll need a tube needle for your vise, figure out which tubes fit it, and get a feel for thread tension on plastic rather than metal. Once you tie a few, the workflow starts to click. Starting your tube by visualizing where the hook should be in relation to your longest materials, like the wing or other long flowing materials, is the biggest tip I can offer. You don’t want the hook trailing too far behind the fly, just as you don’t want it nesting deep into it.

SMALL FLIES ARE A PAIN

Tying micro patterns on tubes is possible—but it’s not pretty. Between the bulk of the tubing and the lack of a hook bend to anchor materials, fine control gets tricky.

Tubes really shine in medium to large patterns—think streamers, leeches, Intruders, and large waking patterns like mice.

Getting Started on Tubes

Here’s the good news: Getting into tubes doesn’t require a full kit overhaul.

Start with a tube needle—a small mandrel that fits into your vise jaws and holds the tube in place while you tie. These cost next to nothing and come in sizes matched to different tube diameters. From there, you’ve got two solid paths:

Tube Systems/Kits: ProSport Fisher is an excellent choice if you prefer structure. Their system features buoyant poly tubes, weighted tubes, cones, discs, and junction tubing. You can build flies that sink, hover, or float. It’s an excellent, well-integrated system—but you’ll probably find yourself wanting everything they make.

A la Carte Tubes: If you’d prefer to keep things simple (and save a few bucks), there are plenty of a la carte tube assortments available. I especially like the translucent tubes from Canadian Tube Fly Co. (Speckled Scandinavian is my jam!), which come in 10–15-inch lengths—plenty for tying several large flies from a single tube. Junction tubing is an uncomplicated equivalent to ProSport Fisher hook guides at a fraction of the cost and makes for a great substitute.

At the end of the day, with just a needle and a few tubes, you’re ready to start experimenting.

A Basic Modern Scandi-Style Tube Fly Recipe

- Thread: Semperfli black 50D Nano-silk

- Tube: ProSport pearl sparkle

- Hotspot: Semperfli 2mm pink Suede Chenille

- Tail: Purple marabou

- Body: Pearl flatbraid

- Collar: Semperfli 8mm purple Pearl

Chenille - Shoulder: 3 wraps pink marabou, 3 wraps kingfisher blue marabou

- Flash: 2 strands of flash

- Head: ProSport small nickel bead

A Flaming Finish

My juvenile pyrotechnic side wouldn’t let me finish this column without mentioning the best part: finishing a tube fly with fire!

Once you’ve tied your masterpiece, you’ll need to flare the tube’s head to lock in your materials. That means heating the end until it curls back on itself. Watching that clean edge roll over in the blue flame of a lighter feels oddly satisfying—a rite of passage, almost.

Just be warned: Tying materials and open flame do not mix well. Keep the flame (and your fingers) a safe distance away, or your first tube may come unraveled in a puff of smoke!