La Brea, my one-year-old dog, has her own sense of time.

At exactly 5:30 a.m., her familiar ritual begins: a gentle paw against my arm, an ice-cold nose pressed against my cheek—enough to wake anyone up—and her insistence that I scratch her belly and rub behind her ears. Her black-and-white coat, as if she had rolled in tar, is the reason for her name, La Brea. Normally being awakened this way would be an annoyance. This morning, though, I’m grateful for her persistence. Through the RV window, the sky is still black as pitch. Perfect. I haven’t missed the magic hour.

I slip out of bed, run a cold washcloth across my face, and brush my teeth while the coffee pot hisses softly on the stove.

Coffee in hand and flashlight on my cap, I slip out into the darkness, doing my best not to wake my wife—a small act of self-preservation before any fishing trip. On the picnic table outside rests my 5-weight fly rod, still rigged from the night before. I know today will require a smaller fly than the one I finished with yesterday evening. Under the dim circle of light cast by my headlamp, I tie a length of 4-pound tippet to the 6-lb mono with a surgeon’s knot, then secure a size 16 Adams. Satisfied, I glance up and catch the first faint purple glow of morning to the east.

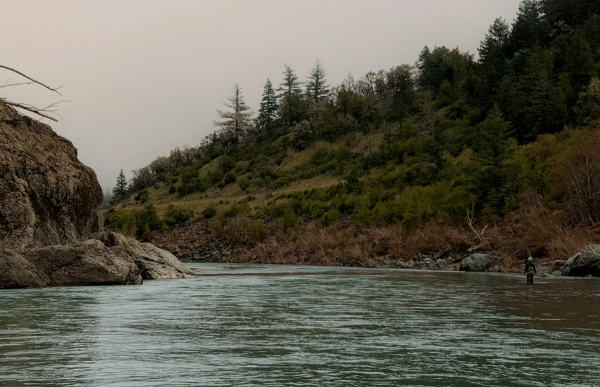

Crater Lake in Lassen National Forest is not to be confused with the vast, blue crater of Oregon. This one is smaller, tucked quietly into California’s volcanic country. From my campsite, it’s a short walk—maybe 200 yards – to the shoreline. The campground that bustles with families and laughter by day is silent now. A soft September breeze drifts through the trees, warm against my face. Each footstep makes a faint scuff on the asphalt path, while the strap of my fly bag rubs rhythmically against my shoulder. The air is rich with the scent of pine needles, that clean, resinous perfume that instantly grounds me in the forest. “God, I love this,” I whisper to myself,

The trail bends, and the trees part to reveal the lake. Crater Lake is a volcanic caldera, formed by the collapse of a once-active stratovolcano. What was once violent and chaotic is now serene—a pool of deep blue set like a mirror among the pines. At 300 feet deep and only a third of a mile across, it is perfectly scaled for quiet mornings like this. I take a sip of coffee and set my bag down on the moist ground.

The water is calm. No fish rising yet, which suits me just fine. There is something precious in this pause before the activity begins—the stillness, the anticipation, the feeling that the world hasn’t quite woken up yet. I savor the warmth of the coffee, the cool air filling my lungs, and the simple grace of having nowhere else to be.

Then, a sound breaks the silence. Off to my right, a playful splash echoes across the water. My eyes scan the surface while taking another sip of coffee. Moments later, another rise to my left. The trout are beginning their morning ritual. I set my cup on a rock and remove my fly from the hook- keeper. “Let’s get this show started,” I think. I strip a few arm lengths of fly line from my reel. Then with a firm back cast, I feel the loose line slip past my fingers as I form a loop, then on my forward cast the line unfurls sending the fly 20 yards out. I watch while the fly stays motionless on the surface, then start a slow figure eight retrieve, watching the fly create a small V-shape following it as it parts the water. No strike on the first cast. Nothing on the second. On the third, things change.

The fish is on.

The rod bends and pulses with each surge. “I should have used my 3-weight rod,”

I think to myself, wanting to feel every movement of the lively trout. From a distance, I get a flash of the pink band glowing like embers. These are Eagle Lake rainbows, planted here from the famous waters west of Susanville. Though smaller than their broad-shouldered cousins in Eagle Lake proper, they are no less spectacular – sleek, vibrant, and breathtakingly beautiful. This one runs hard, tugging the line with a determination that belies its size. I let it tire, then guide it gently to the net. I kneel for some time, admiring the God-given colors on this small trout, a relic from the last ice age. The vibrant pink color across the lateral line is astonishing, framed by dark black spots along the olive back, tail and soft white belly. The gill plate adds even more complexity as it reflects additional colors of teal, turquoise, and yellow, while it moves rhythmically, attempting to filter in oxygen. I’ve seen many rainbow trout in my time, but this one takes the cake.

Partially because of its smaller size, but also because this little guy’s ancestors came from Eagle Lake. “Time to get you back in the water,” I whisper as I watch him swim away.

By the time I land my second fish, I know I am finished. There is no need to score more catches. Last night I released five. This morning, two more. It is enough. I sit back, sip the last of my coffee, and take in the scene: the circle of pines around the caldera, the mirrored surface now dappled with the rings of rising trout, and the sky brightening into day.

Fishing is never just about catching fish. It is about moments like this, where time slows and memory takes root. The subtle sound of the drag mechanism, the flash of silver—all of it etched into the mind’s ledger of experiences worth keeping.

I scan the lake one last time before packing up. The trout are still rising, the day just beginning for them. I sling my bag over my shoulder and head back up the path toward camp, where La Brea will be waiting, tail thumping against the RV floor. My heart is full, my mind quiet, and I am content.