I came to fly fishing late in life, about a decade ago, in my mid-fifties. It is a wonder that I came to it at all, given my background. My father never spent a day in the outdoors, if you exclude his time in the service. He owned a nightclub, and his “time on the water” was in a cabana near a pool on vacations with my mom in places such as Las Vegas or Miami. I went on a few camping trips as kid growing up in the Midwest, but these were infrequent. I first developed an appreciation for the outdoors when I went away to college in Colorado, where I took up hiking and camping, but not fishing.

I had friends who fly fished, but it wasn’t until over thirty years after graduation that I held a fly rod in my hand. Like everyone else, I saw the movie A River Runs Through It in the early 1990s. I even read the novella by Norman Maclean, but it wasn’t until much later that I was sufficiently motivated to put myself to the task of mastering “the four-count rhythm” and the grace required to get a fish to rise.

My first real introduction to fly fishing came from my friend and former boss, Smitty. While smoking cigars on his back porch in the evening, typically after at least a few scotches, he would regale me with his fishing stories. These tales usually involved catching scores of fish and wild adventures in some far-off place. Discounting the effect of the scotch and his exaggerated banter, or maybe because of it, these stories appealed to me.

It was on one of those evenings, after one too many scotches, that we came up with the idea of taking off on a fishing trip. I was in a rare state of mind, with enough impaired brain cells that almost any idea would have sounded radiant. We would leave from our home in Southern California and eventually make our way to Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

It was late summer when we loaded up Smitty’s taxicab-yellow Hummer and strapped his green plastic canoe to the top. When we were done, Smitty stepped back to admire the handiwork. “Now that’s what a fully provisioned fishing vehicle looks like,” he said. I looked at it, but the only thought that came to mind was “corn.” With the canoe perched awkwardly on top and the striking contrast between the green and yellow, it looked like a really big ear of corn. More precisely, an ear of corn with the husk partially removed, mounted on four wheels. It could have been a float in the Rose Parade for the Corn Industry. I kept my thoughts to myself.

When we had planned our fishing excursion that night on the porch, I wasn’t in the mental condition to consider all of the details. Smitty was a committed cigar smoker, and in the twenty years that I had known him, I rarely saw him without a cigar clenched in the corner of his mouth. I assumed he took it out for certain personal activities, but driving was not one of them. I realized that I had just obligated myself to go on a thousand-mile road trip with a guy whose vehicle smelled like the inside of a tobacco shop. We would figure it out. That’s what you did with buddies.

We drove north through Utah, stopping to fish a few lakes and reservoirs along the way. I knew a bit about fly fishing, but since I had never actually done it, I watched everything Smitty did, carefully. I noted that his fly collection consisted mostly of imitation ants, beetles, and grasshoppers. He called these his “bugs” instead of “flies,” and his favorite among them was the Chernobyl Ant. He referred to this as his “deadly black ant.” He tied these on his tippet with great conviction, like someone about to engage in a battle with a grossly under matched opponent. Before he picked up his rod to cast, he always smiled audaciously, rubbed his hands together, and said, “Lambs to wolves.” He wasn’t looking for a fair fight.

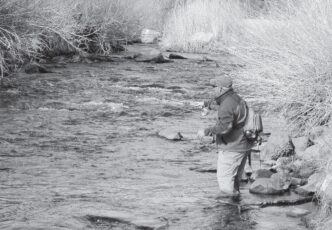

On the water, Smitty’s confidence was infectious. What he lacked in style he made up for with a sense of self-assuredness. He threw his line without flourish, and it landed flatly on the water as if he had never seen that f ly-fishing movie, which, of course, he hadn’t. His lack of finesse did not bother him one bit. He was the farthest thing from a fly-fishing purist you could imagine. He would have used chicken livers to catch fish, but because he had promised me we were going on a fly-fishing trip, by God that’s what we were doing — fly fishing. At least according to him.

Never actually having cast a fly rod, I had only a vague notion of what I was doing. The romantic image I held in my head was of Brad Pitt casting a fly on the Blackfoot River in Montana. Thinking back, I suppose I looked comical. My casts were dramatic. Knowing nothing of the physics of throwing a fly line, I used a lot of wrist and arm movement, which led to wide, arcing loops that splashed down on the water with great force. I looked like a rhythmic gymnast twirling a ribbon or an overenthusiastic orchestra conductor. As in a lot of situations, trying too hard not to look stupid, I looked completely stupid. I was also hopelessly tangling my line, and of greater concern, I wasn’t catching any fish. I knew something must be wrong, so I did what I thought was most logical — I changed my fly. Meanwhile, Smitty had caught several rainbows, all the while chomping on his cigar and repeating each time he brought one to the net, “Lambs to wolves.”

We made our way to Jackson Hole, where we fished the local lakes and river — Jenny Lake, Two Ocean Lake, String Lake, Leigh Lake, and the Snake River. Fishing at the base of Mount Moran in the rugged Teton mountain range, I was awestruck. I still wasn’t catching any fish, but I was doing it in a beautiful place. I have come to understand that this is one of the consolations of getting skunked on a fly-fishing trip.

Smitty wasn’t a pedantic instructor. He gave me a few useful tips, but he mostly let me figure things out on my own. Observation and experience are great teachers. So is fatigue. My wrist and shoulder began to ache with all of my wild gyrations, so I simplified my cast. I was settling down and slowly finding a rhythm. I even began getting a few takes, although I still had not landed a fish. More relaxed, I took notice of the small details in my surroundings. I studied the insects in the air and on the water. I watched for ripples and subtle movements on the surface, trying to figure out if they were caused by fish. I was intuitively working out how all these things fit together. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was becoming a fly fisher.

Smitty is not a big talker, but you need conversation to fill the long hours. So we would talk about spots to fish or what fly to employ. But eventually the talk would become as honest and unadorned as our surroundings — a conversation between good friends spending time on the water.

We ventured out again on our last evening. It was still warm, with a faint breeze as the sun descended toward the horizon and its rays lengthened. We stopped at an oxbow on the Snake River, and I climbed down the bank and waded out onto the graveled shoreline. I tied on a grasshopper pattern that Smitty had given me. I made a short upstream cast to the inside seam of the oxbow. My fly landed softly, and I instantly heard a splash. At the same time, I saw a fish rise to take my hopper. I had caught fish before, just not with a fly rod and not yet on this trip. I felt the strong tug on the line, and it sent a shot of adrenaline straight to my heart. I was like a lone astronomer broadcasting a radio signal for years, trying to make alien contact, who finally gets a response. I jerked the rod and applied a lot of body English to set the hook. Miraculously, after all my flailing, I still had the fish on. The fish thrashed, too, but it was well hooked, and I was doing my best to bring it to hand. I kept constant tension on the line, easing off just enough to let the fish run and then reeling it back in. As I brought it close, I saw it was a beautiful twelve-inch cutthroat, broad-shouldered and healthy. I kneeled down to take out the hook, and just as I did this, the fish flopped and spit the fly. In an instant it was gone. I stood there, breathless and exhilarated. Smitty had witnessed the whole event. I looked over to him and said, “Hollywood release.” He grinned widely and said, “Lambs to wolves.” I grinned back, and with a great sense of satisfaction, repeated, “Lambs to wolves.”

As I stood there with the sun reflecting on the water, surrounded by unspeakable beauty, I knew the fish wasn’t the only thing that had gotten hooked on that summer evening. With that one strong tug I had been pulled into a hallowed trinity of water, fish, and camaraderie.