This is the first installment of a three-part series.

From the late 1940s and through the 1950s, I had the good fortune of spending a great deal of time at the Russian River. My uncle Phillip Wood’s family had a perfect little cabin at Summer Home Park, built in 1909, and that’s where we stayed.

Phil was a dedicated, sophisticated fisherman who developed a curiosity about fly fishing even before World War II, in an era when it was neither popular nor widely practiced. In our youths, Phil’s son Tom and I lowered baits over the side of the canoe, but it was written that in time, we too would take up the fly rod.

By the early fifties, talk along the river eventually always came around to an eccentric loner named Bill Schaadt who fished every day. It was whispered he had some magical ability to know exactly where the fish were. By this time, my whole being was obsessed with fishing, and I longed to catch even a glimpse of this mythical wizard, but lacked the transportational wherewithal to do so.

It was in 1953 when an article appeared in True magazine by Ted Trueblood titled “ With Their Muscles Sheathed in Silver.” It was about shad the fish and Schaadt the man, both pronounced the same.

With that prompting, Phil took us out to the pools of the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club to get us started on the right foot, and we at least learned to cast well enough to fish.

The following spring, we went out on the river, starting at the Summer Home Park Hole, known to be a good spot for many years. Carl Ludeman, credited with creation of the simple, basic tinsel and red chenille shad fly that everyone used, had a cabin there and fished it often. The justly famous and highly respected sportsman Jules Cuenin frequently mentioned it in his newspaper column. Phil had fished there with great success right after he came home from the war, success that totally eluded us eight years later.

Phil had heard of a sporting goods store in Guerneville called King’s News and Tackle where a man named Grant King was tying and selling flies, not only for steelhead and salmon, but for shad, as well. Grant, who twenty years later would become a dear friend, was at the time a difficult blowhard only a mother could love. He obnoxiously insisted we buy some of his special flies, then take them down to the Monte Rio riffle. We were not a family of any means, and back in the car, Phil was fuming. “Thirty cents for two cents worth of material on a one-cent hook. Jesus Christ!” A sentiment that before long would propel us into McCaffrey’s Sporting Goods on Montgomery Street in San Francisco in a quest for hooks, thread, and feathers.

At the Monte Rio riffle, three people were shad fishing unsuccessfully, and now they were joined by the three of us, which added up to six straight rods experiencing the lifeless pull of the current.

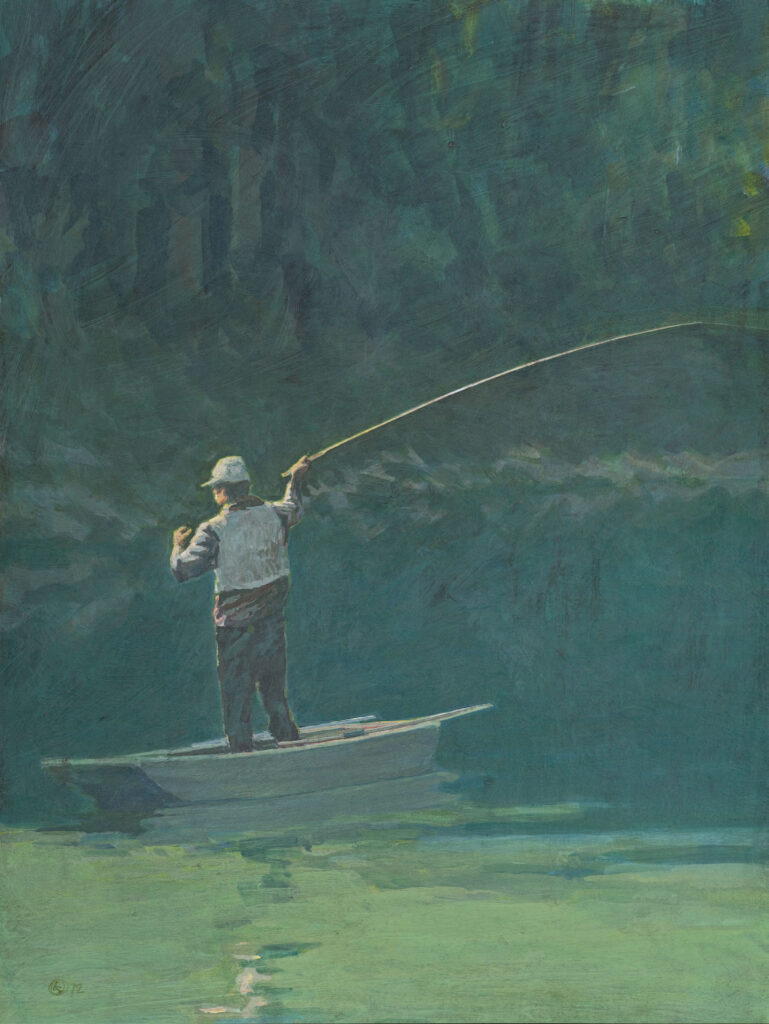

After some time, a cacophony of rattles and squeaks could be heard coming out of the willows across the river alongside Dutch Bill Creek. These materialized into a mud-encrusted 1930s vehicle that skidded to a stop on the narrow beach. Out jumped a man in a hickory shirt and jeans, pulling with him an already rigged fly rod that had been doubled up inside the car. He literally danced out onto the rocks with no waders, no vest, or any other visible accoutrements and launched into a furious blitz of casting. Although I knew next to nothing about it at the time, I sensed something out of the ordinary was going on.

Soon, he noticed a couple of seagulls circling overhead and began jabbering at them, taunting them to come closer. Then he slanted a throw right at them and, laughing out loud, cried, “Damn near tangled up those sons of bitches!” I was right across the river, maybe a hundred and twenty feet away, watching with incredulity. Then, the next thing we knew, he had a shad bouncing around out at the end of his line. The man next to me said shaking his head, “That’s Bill Schaadt for you.”

By the fall of 1957, having been able to drive for two years, my compulsive love affair with the Russian had led me to meet all the regular fly fishermen, of which there were not very many back then. Chief among them, aside from Bill, was a man named Frank Allen, who remains today, years after his passing, one of the two or three finest anglers I’ve ever known.

It was he who instructed me as to proper rod actions, line lengths, weights, diameters and tapers, leader specifications, the best hook designs, and appropriate fly construction. He also introduced me to Doug Merrick and the Winston Rod Company, as well as to Myron Gregory, former world champion fly caster, who, along with Leon Martuch at the newly formed Scientific Anglers Company in Midland, Michigan, formalized the numbered weight concept for fly lines in universal use today. Best of all, perhaps, he included me in forays with Jon Tarantino, one of the greatest casters of all time.

Frank showed me places and ways to fish the Russian, Gualala, and Eel Rivers that I doubt I’d have discovered alone. In turn, I showed him everything I knew about striped bass in Tomales and San Francisco Bays. It wasn’t much really, but at the time, I was the sole practitioner on the West Coast.

Frank would fish for anything, anyway, any time, though of course fly fishing was always what he preferred. During the winter, when the rivers were out, for example, we used shrimp on light spinning gear to catch hundreds of what he called “pogies” around the pilings of the waterfront houses out at Marshall on Tomales Bay. These were in fact surfperch.

Shad were his favorite in the spring. So in the season of 1957, he began my lessons on the Russian. We got in the habit of stopping to have lunch at a tiny hot dog stand in Monte Rio called Ramona’s, a shack still standing today, although boarded up and leaning precariously toward the downhill side. At the time, however, it was clean and bright, buzzing with activity because of its proximity to the beach. The word “Ramona’s” was beautifully painted on both the front and side by Bill Schaadt and signed underneath: Shad Signs. At the time, I was learning sign painting, a nearly lost art today, and was stunned by Bill’s artistry and said so to Frank.

“You know Bill, don’t you?” “No.”

“What? That’s ridiculous! As crazy as you are about fishing. We’ll go over to his house before we go back out on the river.”

When we pulled up to the house, Bill was painting a sign beneath a canvas awning, because the garage had yet to be built. Frankly, I was trembling as we were introduced, then he offered his enormous, powerful hand, and I’ve never felt anything like it before or since.

His manner was guardedly brusque, but polite by any standard, his bearing regal, exemplified by a noble nose and dark, piercing eyes. I could scarcely believe I was standing there.

“Russ has figured out how to fly fish for stripers in Tomales and in the bay off San Rafael,” Frank offered.

“That right?” said Bill, his eyebrows raised a bit. “I’d like to hear more about that sometime, but right now I have to deliver a sign to a guy who’s waiting for me over in Forestville.”

A couple of weeks later, as shad season was winding down, I was back at the

river for a last shot at them at the mouth of Austin Creek. There were a few schools of down streamers holding there, but not enough for consistent action. Back at the car, I dealt with my natural reticence and drove to Monte Rio. When I pulled up to Bill’s place, the Dodge was gone, but there was a woman sitting on the porch, so I approached the house.

“Bill’s not here.” she said. “Come sit and visit with me. I’m his mother.”

It was a warm June afternoon, and on the table in front of her were some beautiful, ripe early tomatoes, a couple of cucumbers, and a purple onion, which she began slicing. “I’m making a nice summer salad for supper.” She said. “I hope you’ll stay and have some with us. Bill’s over-painting the church. Oh, he’ll do anything for the faaather.” And she said it with a sarcastic faux Irish accent.

I was to learn that Bill was a devout Catholic, and all during the fifteen or so years we fished together, no matter where we were, he reeled in on Sunday morning and went to mass, even if the bite was on.

Bill and I didn’t know one another at all yet, naturally, but when he pulled up and got out, he was cordial as can be. I asked if he would show me his brushes, since I was not only an artist, but had an interest in sign painting, as well. The beautiful chiseled greyhounds in various sizes were carefully laid out and glistened with mineral oil, and he also had a striping kit. Though dulled by time and dirt, the Dodge was elaborately striped throughout with the utmost precision, originality, and sensitivity.

We sat and had our simple, but elegant supper, and I watched as Bill ate with studied care, which I would learn he always did, just as he applied similar care to all his endeavors small or large. I was in complete thrall, as if in the most pleasant of dreams.

As we sat eating, Bill said to his mother, “Ma, you been talking to those girls downtown?”

“Why, I don’t know what you mean Billy.”

“You know what I mean. I went into the bakery this morning to get a couple of doughnuts, and that one dark-haired girl says to me, ‘What’ll it be bachelor Bill?’ ”

“Oh, no, Billy. I haven’t been talking to anyone.” she said with a mischievous twinkle in her eye.

“Well, don’t.” And he let it go.

When we were done, he said, “Let’s go out until dark and catch some bluegills, crappies, and if we’re lucky, a couple of bass. I have a boat tied up to the willows at Angelo’s Pool.”

As we floated off, he handed me a peculiar, rather crude deer hair bug he’d made. “You have to get it back into and under the willows, because that’s where they are. We’ll keep the bigger crappies, which are the best eating, and then throw back the rest.”

There was no noticeable current where we were, and Bill eased the boat along, keeping about twenty-five feet from the willows. I fired a cast at a twelve-inch hole in the branches, missed, and got hung up. Bill laid down the oars, picked up his rod, and in one fluid motion sailed his bug right through the center of the opening, where it landed three or four feet back and was nailed instantly by a nice crappie of three-quarters of a pound or so.

“Is that what you were trying to do?” He laughed, grinning from ear to ear.

And so it went for the next hour as Bill pulled crappie after bluegill after crappie out from under the overhanging willows. Me? Never mind.

At last we pulled up to a gravel bar on the other side of which was a relatively fast-moving riffle. Totally ignoring me, Bill sprang from the boat and skipped to the water’s edge, where he quickly cast his bug in every direction, giving it life, until there was a good boil and a whoop as a two-pound smallmouth surged off. These fish are three times stronger and faster than largemouths, but Bill had it on the beach in about fifteen seconds. And thus it was my first outing with him, which was a completely unexpected clinic.

A couple of weeks later I was with my family at Summer Home Park, and I decided to go visit Bill one morning. As I pulled up, he was walking across the yard, and he said, “Get in, let’s go up to Salt Point and catch some black snappers.” By this time, all the hot shots were using one-piece nine-foot Lamiglas rods. The blanks cost six dollars, but somehow Grant had them on sale for three. However, even that at the time was a reach for me, but Frank had given me one as a present, which I quickly assembled and wrapped up. Ted Halvorson, an old tugboat captain who hung around the Winston shop and the pools, had a supply of Sunset Dacron shooting heads that cost seven dollars in the sport shops. But he sold me a beauty for two-fifty. I still have it fifty-five years later. For the ocean, however, Dacron was useless. You needed lead line, and we used a type meant for trolling and that was next to free.

Doubling my rod over and pushing it in the car next to Bill’s I climbed in. By this time, as the end of its life grew near, grass was growing on its bumpers and some high-pitched squeaks told me a family of mice had taken up residence under the back seat. I could have cared less. I was actually sitting in the notorious 1937 Dodge, the most famous car on the North Coast, and I was giddy with excitement.

So off we went, past Jenner and up onto the treacherous cliffs between there and Fort Ross. I suppose it was two thousand feet from the edge of the road, more or less straight down to the black rocks below. In contrast, my knuckles on the door handle were white as a sheet.

On one hairpin turn, Bill said, “See that old pine there? Saved my life once. Charlie Napoli and I went to the Gualala one time. Had a long, hard day. Napoli says he’d drive back, so I go to sleep. Next thing I know, there’s this jolt, and I sit up. Charlie’s face is filled with fear, and he says, ‘I fuckin’ fell asleep.’ ” Bill went on, “The car was wedged against that tree with nothin’ but air under us. We eased carefully and slowly out the driver’s side and rolled out onto the road. Wrecker saved the car.” All the rest of the way to Fort Ross, where the road becomes safe, I never took my eyes off Bill’s face.

In those days, the road was much narrower and far more dangerous than it is today. There were no guardrails of any kind anywhere. If you pulled off at almost any turnout and looked down, you could see the twisted remains of any number of vehicles. At least a half dozen a year took the swan dive with nearly predictable regularity. Again, later on the drive home, I never for one second took my eyes off Bill’s face until we were safely in Russian Gulch, lest his lids droop.

When we reached the place Bill wanted to fish, it was yet another cliff, although hardly as precipitous or as high as what we had just driven over. Still, Bill had outfitted it with a thick rope that was not visible from the road, lashed to a tree. It dangled down about a hundred feet. At the end of it there was still another hundred feet of rough rocks before you reached the sea. The various fishing vantage points were all at least thirty feet above the surging surf.

Our lead lines sliced through the air and cut easily into the swirling cauldrons of wash. The rockfish came fast and furious, most weighing two pounds or so. We swung them up onto our rocky platforms until we had about two dozen, which I questioned, since we had an Olympic event ahead of us getting back up the cliff, even without fifty pounds of fish. As we headed back, Bill grabbed the stringer and literally leapt from rock to rock, any slip at all being at best disabling and at worst fatal. From some distance, I saw him go up the rope like a monkey.

At the time, I was rowing good distances every day, so I had little trouble with the rope. By the time I got to the car, however, Bill had enjoyed a half-hour nap. He had gotten the fish up by means of a long half-inch rope with which he brought them up hand over hand.

In the years that followed, more often than rappelling down dangerous cliffs, we launched at Fort Ross as long as the surf was manageable. With this mobility, we could get outside the kelp and move along the coast, constantly fishing to new fish. Yes, we swamped a few times on the launch, but that was just part of the deal. In this particular environment, the catch was a mixture of black and olive rockfish, and when we hit a pod, a frenzy commenced. As the school elevated, you could get an idea of their vast numbers. On most occasions when this happened, we caught at least one lingcod. These averaged about fifteen pounds.

The thing is, not once did even one of these creatures ever bite our flies. What would happen is that at some point during a blitz, one of us would be pulling up a struggling rockfish, when suddenly the darting and dashing of the two or three-pounder was replaced by a solidly resistant weight. When this happened, we knew a ling had seized our quarry and had it firmly gripped in a huge mouth fully armed with many long, sharp teeth. The procedure then was to pull the beast up steadily to the side of the boat, where we could get a small gaff hook somewhere in its enormous mouth. It never ceased to amaze us as the cod appeared from the depths, snapper gripped in its mouth, looking not unlike a fierce bulldog grasping its bone, dark eyes blazing with defiance. They just would not let go. We learned the hard way that you needed to kill them pronto.

Early on, a very much alive ling that had been sitting still in the bottom of the boat for ten minutes made a ferocious lunge at me, sinking its long, sharp teeth into the toe of my shoe, which quickly filled with blood and hurt like hell. Bill quickly jammed a knife into its brain and then pried its jaws open. We had nothing for first aid, but we continued fishing anyway. That night, infection set in, and it took a course of antibiotics and about a week to clear things up.

On one occasion, just outside Fort Ross Cove, Bill and I were fishing and there were three skin divers there. After a time, one of them surfaced about fifty feet from us with what might be described as much fanfare.

“Help! Shark!” he cried out. Bill picked up the oars and began hunching in his direction, and within less than a minute, we were pulling him over our gunwale. He sat limply on the floor of the boat, breathing heavily.

“Big bastard.” he rasped. “Came up behind me and took my net full of fish. It was tied to my belt, and suddenly I was being dragged along. Good thing I had a knife so I could cut myself loose.”

I scanned the water around us, which was quite smooth, and all was quiet. Then I saw it, no more than twenty-five feet off our stern, just like in the movies, a scimitar of a dorsal fin making a half circle around the boat. As it moved to where the sun was behind us, we could see its mass, twelve, fifteen feet, who knows?

“Hey Bill” I said with urgency, “It’s time to get the fuck out of here.” Not needing any prompting from me, we were already practically surfing toward the beach. On one warm, dead-calm, early September day, we were once again headed up the coast. Bill pulled over at Jenner above the mouth of the river. It was open, but narrow, with a very small surf of not more than two feet curling and breaking on each side of a narrow trough.

So we turned the Dodge around and put it down on the beach, where we offloaded the boat. It took only a few minutes, and as we were shoving off, a man and woman came walking by with a black Lab.

“Goin’ fishin’?” the man inquired. “Yep.”

“You gonna fish in this big lake here?” “It’s not a lake.” I informed him. “It’s a lagoon at the mouth of the Russian River. We’re going to row out through it into the ocean to those huge rocks you see out there.”

“Oh my.” The woman said. “ That sounds like it could be dangerous. But I guess you have your life jackets.” She may as well have asked us if we had our castor oil, and off we went.

I asked Bill to let me row. Not that he couldn’t, because he was in spectacular shape his whole life. But I was not only seventeen years younger than he, but because of the striper fishing, I was rowing all over the bay every day, and it had by this time become second nature.

As we approached the opening, I swung us around so I could see what was going on with the tide and the waves. Even if we swamped, it wouldn’t really be dangerous, just messy and inconvenient, so we really didn’t want that.

I said to Bill, “I’m going to hit it straight on at top speed — that OK with you?”

“Go for it.”

We surged ahead, taking a wave over the bow that got us wet, but we were suddenly in the ocean, and both of us were grinning like Cheshire cats.

Now we were out at the closest big stack, rising and falling on the swells. The rockfish swarmed us, and we had a lingcod experience, as well. Then it was time to go in, because the swells appeared to be growing. Approaching the mouth of the river, I could see the tide had risen so that even though the surf had in fact gotten bigger, it was rolling right through and dissipating in the lagoon, and we just coasted in.

Over fifteen years, Bill and I fished together often in both summer and winter. During the latter, we fished the Russian River at Austin Creek, Brown’s and Watson’s Log Pools, Lone Pine, Forestis, Freezeout, Duncans Mills, Villa Grande, Monte Rio, and Angelo’s Pools. Sometimes there were a few people scattered around, mostly stationary bait soakers, but other than that we were all alone at every venue.

The way we fished the Smith was to float it from the forks on down, the two of us in Bill’s twelve-foot aluminum boat. We’d stop whenever we saw working fish or otherwise at good-looking pools. Most of this water is inaccessible from shore, and I don’t recall seeing even a single other fisherman, year after year.

On our drifts, we encountered every situation imaginable, and to fish some of them called for a little thinking outside the box. In those days, there was no such thing as a guide, at least I never heard of or saw one. This meant that in all those years, we never had to fish a piece of water that had a single line in it before we got there. I might add that we took this fact completely for granted.

Sometimes we’d drift for hours without seeing or hooking anything. After all, it was early in the season, and we were upriver. Once, after a long dry spell, we got out to fish a hole where the current ran straight into a cliff. It was obviously deep as hell, and the water was swelling and boiling in a chaotic, confusing manner. We were doing our best mountain goat imitations, and it was not lost on me that one slip could plunge either of us into the drink, where we would have quite the swim ahead of us.

I had no idea how to fish this mess, because a roll cast was pushed instantly back at me. Shortly, however, Bill had a salmon on. He was on a narrow ledge six or seven feet above the water. I noticed that right below him was enough of a flat place to kneel about a foot above the foamy swirls, so I wedged my rod into a crevice and inched my way down there. Fortunately, it was not a very big fish, eighteen, maybe twenty pounds, and I got my fingers in its gills and powered it up without taking a header. As I did this, I couldn’t help noticing a teardrop sinker about two feet from the fly as I twisted it loose. Glancing upward, I also saw that plain monofilament ran from the sinker up through the guides and onto the reel. I wrestled the fish to our boat, which was tied to an alder tree. A child’s baseball bat quieted the salmon.

Some years earlier. I was fishing the Gualala with Frank Allen, and as the days passed, he drilled me on what worked and what didn’t and where. The uppermost pool, where you could reasonably expect to hook a steelhead, was the lower end of the Donkey Hole, and you needed a weighted fly to do it.

I was surprised when he said we were going to have a look at Switchville, the next pool upstream. It was a dream bend for “rolling berries” — fishing roe — and when I was younger, I hooked quite a few fish in it. Three guys were there. Two were hopelessly soaking baits with their poles propped in forked sticks, a fire going and coffee cups in their hands. The third was working the hole correctly, by methodically tumbling his roe through the good slots. He hooked a fish as we were looking on. “OK,” Frank said. “Lot of fish hold in this lower end, but it’s too narrow and too fast to swing a fly through it. Neither Curtis [Al Curtis, one of the best fishermen on the coast] nor Schaadt has ever been able to hook up in here.”

“Then what the hell are we doing here?” “I came in one day and Bill was playing a fish, and I couldn’t believe it. So I walked down to watch, and that’s when I saw the sinker.”

“How did he cast it?”

“Simple. It’s called Oakie fly fishing. You take off the fly line and lob the thing out there and bounce it along just like a bait using only your monofilament.”

“You’re joking.”

“If it offends your purest sensibility, sit back up on the bank out of the way and play with yourself.”

“Shit no, I’m in.”

And we each hooked a fish.

Meanwhile, back on the Smith, Bill hands me a teardrop sinker the same as his.

“Oakie fly huh?”

“It’s that or nothing in this nightmare.”

So I took the lead line off and rigged the sinker, which shortly had me on a salmon. Bill hooked one more, then nothing, so we continued on our way, lead line back on.

On a different trip, we’d drifted quite a while without anything and were backing through a slow pool when in the distance, a fish showed. It threw some spray that the sun caught, or I might have missed it. As we drew up to the lip of the riffle, another fish rolled.

When we were closer, the situation revealed itself, and it wasn’t very attractive. The river split, with a smallish channel on the left, while the main flow stayed right. It was narrow and fast at first, then slowed eighty or ninety feet down. Willows crowded one side, and on the other was a steep bank.

“What do you think, Bill? We can’t fish this, so why don’t we slide on through it and keep going?”

“Not so fast,” he said, just as another salmon rolled. “Get on the anchor and drop it when I say.”

Bill positioned us on the seam between the fast water and the eddy and started stripping mono from the reel. I had no idea what we were doing. I was further mystified when he cast straight downstream, his fly landing right where the fish were showing. These fish are lying deep, I thought to myself. Does he really think they’ll come up from the bottom and take? Instead of polluting the atmosphere with a childish question, I kept my mouth shut.

Then I saw that he was bringing back line in long pulls, unlike any retrieve I’d ever seen. Then the shooting head splice was just off his rod tip. Instead of roll casting, then making a new cast, he was now applying his usual strip. The splice had vanished, and when I looked more closely, I saw that the monofilament was running out, not coming back.

When it was tight to the reel, Bill manipulated the line, bringing a little in, then paying it back out. He also slowly, but deliberately changed the angle of his rod. Then he set the hook with a burst of laughter.

Since it wasn’t my first rodeo, I surmised correctly what I’d just witnessed. The cast was to establish exactly how much line was needed to reach the fish. Then it was pulled all the way in and released. As it went with the current, it sank at a downward angle from the rod tip, and when all the line was out and tight to the reel, in theory, the fly was swimming in front of the fishs’ faces. By moving the rod from one side to the other and bringing the line in and out, Bill probed a ten-foot square of water. It was brilliant.

“One small question, if you don’t mind my asking,” I said. “What’s with the fake retrieve as the line plays out?” “That was for your benefit. If anyone’s got their eye on you, which trust me, they will if you’re catching fish and you have to use this tactic, you don’t want them to know what you’re actually doing. As far as they can tell, you’re just casting and retrieving.”

“Oh.”

Concerning the Chetco, during fall, when the water was low and clear, the bait-and-lure boys did not bother to go near it, and there weren’t any fly fishermen. The last year I ever fished it was 1966, and I was all alone at Tide Rock, putting on fish after fish. Bill had found fish in the Bailey Hole on the Smith and wouldn’t budge. He wanted a shot at the big guys, which the Chetco didn’t really have. I fished Bailey with him the previous day, and we had to get there stupidly early to beat the five or six other boats. That just didn’t hold any appeal for me, and I never went back to that type of lineup fishing.

We fished the Klamath and Trinity in early to midsummer, when there was never a single other fisherman. Likewise, the Eel, where the very few people throwing flies around the periphery of the vast pools were happy with their ten-inch halfpounders.

On the other hand, the fresh kings were in, and as we discovered to our surprise, so were some serious steelhead, and not just four or five-pounders, but the real deal. They came to sparse number tens, big double-digit chromers, the first of which broke us off instantly, leaving boils the size of a washtub. On guard later, a light touch let us put some on the gravel bar. At that time and under those circumstances, the kings were problematic, because they were holding in deep water too far out to reach on foot, usually in the Singly Pool, and we didn’t have a boat this early in the season.

One of the things we looked forward to each year was the down-streamer steelhead fishing at Austin Creek riffle in March. I fished it more with Frank than with Bill, and even more often by myself. Bill enjoyed it now and then, but the fact that you couldn’t keep a fish dulled his interest, because he used them in his life for the barter system. (The Russian was open year-round for all species except steelhead — hence, catch and release in an era when that concept was unheard of.)

In those days, during the last few years at the end of the 1950s and early 1960s, there was no trespassing on the south bank of the river through Casini’s ranch, except for Bill, that is. The river was usually too strong to cross, so I’d cajole him into going out for a couple of hours, and we had that whole side of the riffle to ourselves.

There were so many fish, it was nothing for each of us to hook ten or twelve. If you made more than five casts without a grab, it was cause for puzzlement.

In those years, the devastating effect of the Coyote Dam had yet to be fully felt, so steelhead numbers remained strong. How strong? No one really knows. And that includes Fish and Game, which has offered up fifty thousand as their best guess. The Russian was a big river before the war, two or three times larger in width, depth, and volume than it is today. During the winter season, when the steelhead ran, it was mostly unfishable. But when it was fishable, Katie bar the door.

The old-timers who lived on the river in the early part of the twentieth century and who fished from that time up through the 1920s and 1930s talked of twenty fish as an average day. Of course, this was on bait. Even lures were not used much, if at all, and fly fishing was unknown. The old boys I sometimes visited with who were octogenarians in the 1950s, when asked about total steelhead numbers, started at two hundred and fifty thousand and went up to twice that.

The second part of this series will appear in our next issue, November/December 2014, and the final part in our January/February 2015 issue.