Readers of California Fly Fisher need no introduction to “Scott Sadil,” who has appeared in numerous feature articles, often supplying an effective twist on an old fly that has worked for him or a new one that has stood the test of experience, but on the way to doing so also pondering what Real Guys — as opposed to the rest of us — do when fishing and how life looks on the way to, in, and on the way back from the stream. However, there is also Scott Sadil, the guy who actually wrote those articles and created that character — a former Southern California surfer who now teaches high-school English in Hood River, Oregon, just up the Columbia River from Portland. The two, of course, are quite similar — sort of like the overlapping figures that make up a 3-D image. Here, we’ve tried to supply the 3-D glasses that bring the two into focus.

Bud: How did a surfer from Southern California end up as an English teacher and steelheader in Oregon?

Scott: The same restlessness and desire for greener pastures that compelled so many of us, or our parents, or their parents to head west continues to send California sports enthusiasts around the globe. We’re everywhere. One of my sisters went to Australia in the mid-seventies and never came back; in every ski town and trout Mecca you find guys with Vince Scully and freeway commuting in their blood. By the time my sons were born, I was ready to leave the suburban sprawl of Southern California and, in the process, trade in my surfboards for fly rods. My wife at the time had family that had moved from Roseburg to Portland. We showed up — but it turned out that life in Multnomah County wasn’t that much different from life in San Diego County, despite the change in weather. Then I got hurt while working as a carpenter, I went back to school and got my masters in teaching, my marriage be-gan to collapse, and I got a job offer in Hood River, two weeks before the school year started. It was a big decision — a real game changer. It took me about two and a half minutes to make it.

Bud: Although your first book, Angling Baja, obviously focuses on fly fishing in the surf, in fact, it’s clear even from that early work that you’ll fish for pretty much anything that swims — there’s even a chapter called “In Search of Baja Rainbows.” How did you get to be a fish hawk, and why and how did you become a flyfishing fish hawk?

Scott: My father and his father were serious middle-class sportfishermen. When they arrived home in Whittier from a weekend in San Diego with another trunkload of albacore for my mother to can, it was clear to me that they had been engaged again in fine and noble sport. I was brought up deep-sea fishing, fly fishing for trout in the Sierra, surf fishing in Baja, and probing practically every lake and reservoir from Cachuma to Hodges. Fly fishing, of course, is the natural evolution, as HaigBrown once said, of any serious angler — and the more I traveled looking for surf, the more places I saw, and sometimes fished for, bait-chasing predators that I felt certain would eat a fly. My college pal Peter Syka and I started catching halibut and bass and corvinas and even yellowtail casting lures in the Baja surf — and at that point we were only a step away from doing something that had started, in my life, on those dinky Sierra trout streams.

Bud: I’ve interviewed a number of the pioneers of West Coast surf-zone fly fishing over the years who also started out as surfers. ( Jay Murakoshi comes to mind.) What is it about surfing and fly fishing that makes the connection between them?

Scott: You’re going to have to stop me if I start to say too much about this one. Surfers know more about water — about moving water — than is known by any other living creatures but those that live in water itself. Rivers? I’m sorry — it’s no contest between water moved by gravity and the complicated dynamics of surf, of breaking waves. This intimacy with the ways of water makes surfers of a certain bent ideally suited for the sport of fly fishing. Also, contrary to stereotypes, surfers are often patient, contemplative sorts. They spend a lot of their time quietly waiting. They know how to pay attention, watch for signs, read the water, comprehend what’s hidden beneath the surface. They certainly understand the concept of slots and troughs and riptides and seams — those sweet spots where surf fish hold or feed, which is why as anglers, experienced surfers have such a big advantage over guys who come to the beach from fresh water.

But let’s not mince words. Good surfers are also possessed of an attribute known as the killer instinct. Seth Norman has written often of the predator aspect of the angler in relation to the predator aspect of his prey, and I’ll confess right here that I was always one of the guys in the lineup who wanted to catch the biggest and best wave. Which shouldn’t necessarily be interpreted as competing against one’s fellow surfer or fly fisher. Instead, when you pull into a long, exquisite barrel at, say, Jeffreys Bay, or you hook into a 12pound native hen that has just risen to your waking fly, you are suddenly plugged into a complex, animated charge unlike anything else you get to experience in the rest of your life and that certainly has nothing to do with putting food on the table or making babies.

Bud: I should publicly confess before we go any further that I’ve been one of your editors since before we both had gray hair. Books like Angling Baja and Cast from the Edge had a lot going for them, but had some rough edges. Since then, you’ve knocked off the rough edges, planed, fitted, sanded, primed, and finished your prose — it’s a development that I don’t often get to witness. Most fly-fishing writers need a day job in order actually to make a living, and you’re now a high-school teacher. Did becoming a teacher of English have anything to do with developing your understanding of the writer’s craft?

Scott: What’s so difficult about writing is the amount of it you have to do before you get any good at it — and even after you think you’re doing a pretty good job, you’re probably still a long ways from where you hope one day to be. So you either love the work, the process of chiseling words onto the page, or you grow discouraged by the response of editors and publishers to your efforts and you quit. It should be obvious how much like fly fishing this is. If you’re not going to be happy or enjoy yourself while you’re learning how to do it, while little you do is really that good, you’re not going to stick with the sport or do enough of it to really improve. Yes, those first two books are rough in spots — although not nearly as rough as a couple of other manuscripts that never saw the light of publication. The best thing about becoming an English teacher was that I entered a community of people who knew about literature, who cared about stories and writing. This wasn’t often the case on a construction site — or even in a surf camp. I was also lucky enough to find my way into a writing group as soon as I arrived in Hood River, the very same group I meet with once a month now — although during that time, two members have died and one moved to Canada, where he could afford to have his heart placed on a table and repaired. Certainly teaching English itself has helped my craft, if only because I spend so much time trying to teach the mechanics of how the language works. I should also add that I’m fortunate to teach at a school where I have virtually unlimited freedom to choose what I want my students to read, whether it’s a piece from the new New Yorker or a short story from a collection of fiction by Tom McGuane. Reading good writing, I contend, remains a writer’s most significant source of insight into improving his or her own craft.

Bud: I actually looked up your evaluations as a teacher on ratemyteacher.com. They say that you’re a hard grader who doesn’t reward students who have learned to game the system. They also say “He should never stop teaching, and kids should never stop appreciating him.” Does what you’ve learned as a fly fisher affect the way you teach — and vice versa?

Scott: Oddly enough, I’ve never felt particularly drawn to teaching. That’s a fairly bold admission from someone who has taught in schools for more than a dozen years, who has taught a few hundred students to fly fish in beginning parks and rec classes, and who just wrote a book subtitled Lessons in Fly Fishing Like the Real Guys. What’s with that?

Well, the truth is, I often think of myself as an inadequate teacher because my innate pedagogical stance is from what I call the Willie Mays school of teaching. When asked how to play the game of baseball, Mays said, “When they pitch it, I hit it. When they hit it, I catch it.” Thanks for the help, Willie.

Essentially self-taught as a writer, a fly fisher, a surfer, and in any number of other pursuits, I have a tendency to think that students can learn if you just throw out the balls and have them start to play. That’s the kind of student I was. Most, of course, are not. When I started teaching fly casting, I finally had to think about breaking down a complicated skill into smaller, discrete acts — and lo and behold, I learned to cast better, too. Students in my Honors English classes don’t really appreciate it when I just tell them to write better — so I’ve had to think long and hard about what “better writing” means at any stage of a student’s development. Teaching writing and teaching fly casting are very similar in that your job as a teacher is to find one specific skill or aspect of technique to work on when faced with a student who is actually doing about forty-three things completely wrong. And it should be one element that can lead to substantive improvement. If you talk about more than one, maybe two elements, you’re going to confuse your student, and the frustration begins. Time for a worksheet; everybody loves a recipe for success.

Bud: In Cast from the Edge, the book’s protagonist, the semiautobiographical Francis Sepic, had some rough edges himself, and his character went through some pretty extreme emotional gyrations. In your stories that appear regularly in California Fly Fisher, you’ve found a different voice — a voice that implies a character who often seems to expect the worst, but as a result is rewarded by small moments of grace. The characters in Lost in Wyoming tend to share that outlook. Maybe we all are just getting older, but how did you find a voice that allowed a more nuanced way to represent character? And how would you elaborate on or correct the way I’ve characterized that voice?

Scott: I think of myself as an optimist — the essential attribute and perhaps defining characteristic of anglers everywhere. No matter how poorly we did yesterday, I can come up with a dozen good reasons why today we’re going to knock ’em dead. Nevertheless, life, like steelheading, teaches us that our optimism isn’t always well founded. I now find it useful to be aware that one day I will grow too old to go fishing, that my time here is finite, no matter how many laps I run or cranberries I eat. Or even if I save the salmon.

Age offers other insights, as well. There’s a lovely short story called “Marigolds” that I read with my sophomores, the story of the moment a girl sees herself change from a child to an adult, from a girl to a woman. It has nothing to do with sex. Instead, the narrator recounts tearing up an old woman’s garden, a cruel and senseless act in response to family hardship in the narrator’s life. She gets caught — and when she sees the hurt that the old woman suffers on discovering the destruction of this little patch of beauty that she, the old woman, created to stave off the harsh realities of her own life, the girl feels terrible. In that moment, she loses the innocence of childhood while experiencing the beginnings of compassion. That’s the growing up, that’s the change, but the hard truth learned is that “one cannot have both compassion and innocence.”

Which is a long explanation, for those who are still with me, why readers might have noticed a more nuanced voice in my work. Compassion is the single most important quality that story writers need to develop — at least if they hope to create characters who seem real. In his review of Lost in Wyoming, Chris Camuto at Gray’s Sporting Journal commented: “Like any good short story writer, he” — that would be me — “has affection for his characters.” We all know that writers, like actors, should never read reviews of their work, but I’m proud of that comment, because affection grows out of compassion.

Bud: You write frequently about authority, tradition, innovation, and what really matters in fly fishing. What do you see as their relationship? Steelheading, especially, seems to include strong elements of each of these aspects of our sport.

Scott: There’s a provocative tension in fly fishing between old-school traditions and the latest new-wave innovation that promises finally to make the fish bow down to the ways of the master. I’m married to the idea that anglers of the past still have things to teach us today and that the best of them would have no trouble showing up now and fooling fish. At the same time, you can’t help but be impressed by the development and refinement of equipment — especially with, say, lines for Spey casting or for fishing in the ocean. Then again, is the goal simply to make catching fish easier? Might not there be something else, something more elevated, to which we aspire?

Don’t get me wrong — I’ll try anything. But I recognize again and again that there’s a spirit to fly fishing that doesn’t necessarily equate to the letter of the sport. Just because I have a fly rod in my hand, just because there’s a fly reel attached and I’m casting a fly line and a fly, I’m still able to raise the question, at times, whether what I’m doing is really fly fishing — or at least the kind of fly fishing I find rewarding or simply fun. But I assure you, I’m not a snob. We’re all on our own trajectories, and as Yeats said, our important arguments are with ourselves.

Bud: Lately, you seem to have been “friended” by John Gierach — not on Facebook, but in articles in Fly Rod & Reel and Fly Tyer. You’re the new “A. K.”! How did that come about?

Scott: Gierach, along with a couple of other well-known fly-fishing writers, was instrumental in introducing my work to Jim Anker, who was just then getting ready to launch Barclay Creek Press. Gierach especially liked something I had written for Fly Rod & Reel,a piece about fishing for steelhead in the winter on the Olympic Peninsula — so when he scheduled a trip in winter to Oregon’s Sandy River, we made plans to fish together. It was a fairly typical winter outing — nobody touched a thing, despite good conditions, good water, and Marty Sheppard, a guide as good as they come. Gierach was of the mind that this is nearly always what steelheading is like — but I convinced him he needed to show up in the fall, and then he could count on getting fish.

Throughout all of this, there was also a lot of back and forth about the business of writing, about agents and marketing — stuff that Gierach doesn’t spend any more attention on than you would expect, yet he’s been in the game long enough that if you listen, you can learn a few things. Mostly, I wondered how the hell he’s ended up making a living writing about fly fishing. That’s still a good question — and we’ve continued the discussion, although fortunately it holds a lot less interest to both of us than how he moved some fish in the neighborhood with a floating line and swinging fly.

Bud: I’ve talked a lot about your writing and about your writing about fishing, but not about your fishing. Where are you fishing these days? Do you get back to the surf and the salt much? And do you ever get out of the West?

Scott: I’m pretty lucky — I have a lot of good fishing close by. What’s shocking to me is how many great rivers and how much great water I haven’t fished, despite the inordinate amount of time I’ve spent casting flies. I’m embarrassed to mention, for example, that I fished the Metolius, near Bend, for the first time in my life this fall. That’s another old tension in the sport — whether it’s more rewarding to grow increasingly intimate over time with a few treasured waters or whether you’d rather run around sampling sport here and there, getting a taste and then heading off for the next promise of fun. I do get around — which is one of the perks, of course, of teaching. Lately I’ve been making it down to Baja fairly regularly again, after many years of fishing solely in fresh water. This winter, I’m also spending a lot more time on Oregon’s coastal rivers, which have generally been a hit-and-miss proposition for me, but lately, I’ve developed some contacts who are helping me get dialed in to fishing for salmon and coastal winter steelhead. And, some big news, I just got invited by the artist Bob White to spend a week this coming summer as a writer-in-residence at the Bristol Bay Lodge in Alaska — my first time in that part of the world, and some fairly heady digs, at that.

Bud: You say that you’re an optimist, even though optimism isn’t always well founded. What do you see as the present and future state of fly fishing?

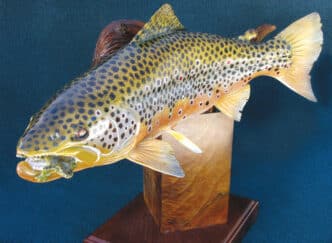

Scott: I wonder more and more what it means that so much fly fishing, especially trout fishing, now takes place in artificially created environments, that the “wildness” that has always seemed to me such a central aspect of the sport — of all sport — has somehow been wrung out of so many places where we now go fishing.

I’m not talking about lodges getting built or McMansions or ranchettes or condominiums lining the banks. Instead, practically every noted trout haven in the West is now some sort of tailwater fishery, a great way to grow and maintain populations of big trout, but not really very different from the concept of a fish hatchery.

Does it matter? Well, of course it does not matter — other than that the sport becomes more and more about learning how to catch those fish in those places, rather than a means of probing and penetrating the mysteries of the natural world, of discovering traces firsthand of the infinitely subtle and astonishing curiosities of life in all its forms — of which we, too, are part and parcel. It certainly doesn’t matter if all we’re here to do is go fishing. Heck, before long, we may be running our oceans through gargantuan refrigeration units if we still want to provide migratory routes for sea-run salmonids. That’s a tailwater concept whose time may soon come. Or we could just pipe the water up to Mars and back — as Mr. John sang, “In fact it’s cold as hell,” even if it is no place to raise our kids. I just wonder who they’ll find to change or clean the filters.

Bud: Here we are at the obligatory Silly Tree Question. If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?

Scott: I imagine myself a western juniper, Juniperus occidentalis, that’s been fortunate to find itself along a cold, clear, sun-blasted rain-shadow river — one of those archetypal junipers that has made the transformation from shrub to genuine tree, stately in its own right, although nothing like my close cousins, the big, prestigious cedars along the coast. Although I stand alone in the harsh Western winds and sun, no other trees — not even other junipers — touching me, I’m actually part of a vibrant social community, visited by the lovely, sweet-voiced passerines, by coyotes and bobcats, anglers, and eager lovers seeking shade and seclusion. Tanagers and orioles get drunk on my fermented berries, and a warm June night can turn as lively as A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I’m old — one of the oldest living creatures in the West, born before Jesus Christ, although not quite as old as the bristlecones — but those guys are so old I don’t think they even grow anymore. By the look of my scraggly bark, you can see I’ve taken a lot of weather, and the truth is, I’ve lived where many, many things can’t live. Which means my wood, my branches and my limbs, have something called character, and when I do finally die, someone may treasure my dense, complex, tightly grained remains, more useful for art than for building any sort of utilitarian structure although, in a pinch, I could also serve as sweet-scented fuel to cook a rustic, romantic meal, and I’ll rival any hardwood, anything they’ve got back East, for a fire to warm you on a chilly, star-studded Western night.