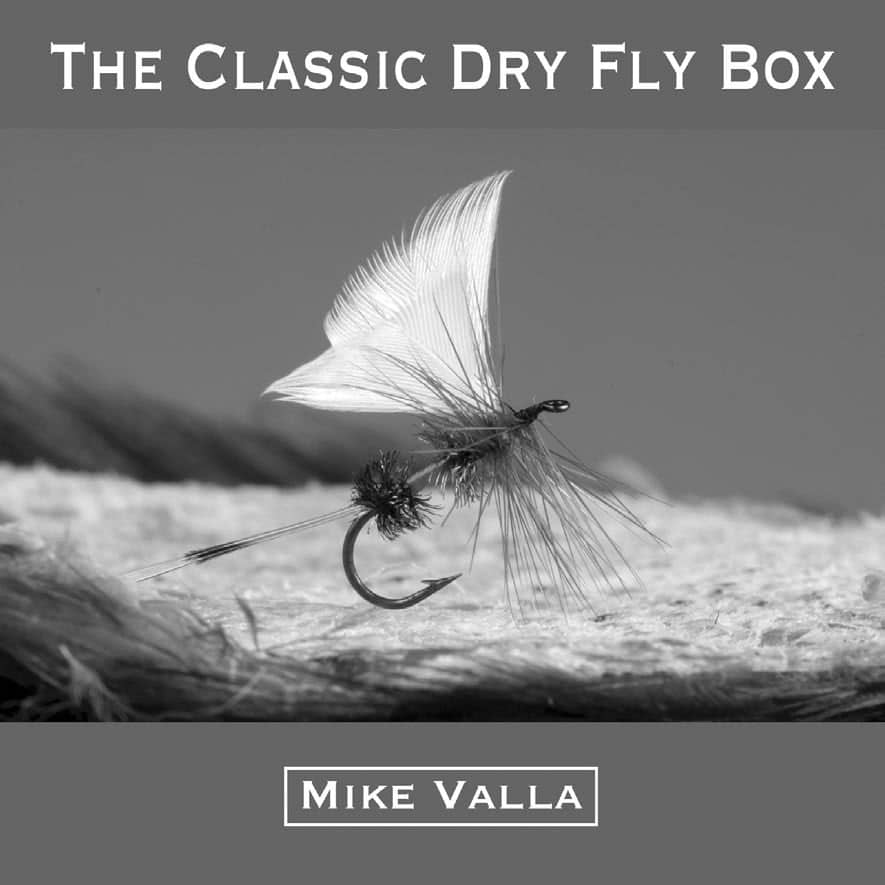

The Classic Dry Fly Box

By Mike Valla. Published by The Whitefish Press, 2010; $24.94, softbound.

What makes a fly pattern a “classic”? Having been around for a while is one obvious criterion — no matter how effective it might be, the latest creation hot from the vise doesn’t qualify. With age comes the likelihood that it’s tied with natural materials — not because tyers in years past wouldn’t have embraced them (they would), but because that’s what was available then. And pedigree matters. “Classic” flies tend to have been originated by major figures in the history of the sport (although attribution is always a tricky business) or at least associated with them in some way.

Flies that meet these criteria are what you’ll find in Mike Valla’s Classic Dry Fly Box. The book surveys 100 dry-fly patterns, with examples all tied by Valla and with brief historical vignettes that help place them in the traditions of American fly tying and angling.

Short of a medium who could channel the spirits of Theodore Gordon, Reuben Cross, Art Flick, and Harry Darbee, it would be hard to find a person better qualified for writing a book like this than Mike Valla. Valla learned fly tying as a teenager at the bench of Walt and Winnie Dette in Roscoe, New York, and he has since become something of a custodian of the heritage of fly-tying in the Northeast. His Tying Catskill-Style Dry Flies (Stackpole/Headwater Books, 2009) is the most accessible introduction to both the techniques involved in tying the Catskill-style dry fly correctly and to the history of fly fishing as it developed in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the region.

Given that history and Valla’s own pedigree as a tyer and angler, most of these “classics” are from the Catskill tradition. Not all, to be sure — Mike Fong’s Flying Ant and Buz Buszek’s Kings River Caddis qualify as classics here, and Valla has said that when he was young, Mike Fong seemed to him to be the quintessential West Coast fly fisher. Constant innovation has put some of these flies “on the endangered species list,” as Valla puts it, but while his intention in writing the book is partly archival, it’s more accurate to say that it’s remedial — to introduce today’s anglers to patterns that were the go-to flies in their day, but that have been eclipsed by the go-to flies of the present. The book shows the continuities, as well as the differences, in how dry flies have been thought of, tied, and used.

Of course, they still work, and not just on the Beaverkill. Some, such as the Variants, Skaters, Bivisibles, and Spiders, are also designed for angling techniques such as dancing a dry fly across the surface on a short line (in effect, the dry-fly equivalent of short-line nymphing) that could be used more often today.

However, beyond the criteria outlined above, all these flies have one other attribute that makes them classics. They’re flat-out gorgeous. Because the Catskill dry has so few elements — hook, tail, slim body, upright and divided wings, and hackle — it’s the variations that stand out from pattern to pattern in a manner that suggests Bach or jazz. John Atherton’s experiments with blending shades and colors, others’ experiments with different kinds of quill bodies, hackles palmered over floss bodies (some of these flies were created as caddis imitations), and variations played on winging materials not only bespeak a fervent inventiveness that rivals anything going on today, but produced a kaleidoscope of fishing flies that are also simply beautiful objects.

Mike Valla’s magisterial tying skills and expert macro photography, which can relentlessly expose any lapses in tying technique, have done full justice to the ideas of the originators of these patterns and to the beauty and balanced proportions of the flies. This is supposed to be the first in a heavy vest full of “classic fly boxes” (wets, steamers . . . you get the idea), so stay tuned. Even if — or especially because — you’ve never heard of a Katterman, a Killer Diller, a Lady Benson, or the Spirit of Pittsford Mills, it’s worth taking a look into The Classic Dry Fly Box.

Bud Bynack

Common-Sense Fly Fishing: 7 Simple Lessons to Catch More Trout

By Eric Stroup. Published by Headwater Books, 2009; $14.95 softbound.

Like many, I learned fly fishing from a mentor or two who more or less passed on to me their good and bad habits, which, over the years, melded into what I thought was serving me very well. Oh, I read some books, paid occasional lip service to a technical article by one of the sport’s gurus, and even watched a video or two. After almost fifty years of managing a fly rod, I had settled comfortably into simply doing what I’d always done, frequently letting the delicious surroundings of “fishing” compensate for the all too frequent lack of “catching.” But then, on a recent trip to Montana’s Ruby River, I met Eric Stroup Eric is an accomplished and engaging guide in both Pennsylvania and Montana whose passion surfaces when he lays down his fly rod and writes. Common-Sense Fly Fishing zeros in on turning “fishing” into “catching” by quickly and concisely getting to the heart of the matter: presentation.

Eric Stroup’s seven lessons, presented in seven chapters, all come back to that basic element. From “Lesson One, Drift,” through “Reading Water,” “Approach,” “Casting,” “Line Control,” “Rod Position,” to the final chapter, “Mending,” Stroup covers what it takes to place a fly on the water in such a manner as to make it irresistible to a feeding, or waiting, trout. Each chapter is short, to the point, and illustrated with elegant simplicity. In 73 well-written pages, the author has the reader itching to pick up a rod, find a stream, and get back to these simple basics that enhance a fishing day by turning it into a catching day. As a bonus, the book concludes with four short chapters on nymphing, dry-fly fishing, rigging, and flies. I recommend this fresh and useful book to fly fishers of all skill levels, particularly those at the expert and guide level. The book also should be basic equipment for anyone teaching or instructing others in the joys of our sport.

Mel McKinney

Love Story of the Trout, Award Winning Fly-Fishing Stories, Volume 2

Edited by Joe Healy. Published by Fly Rod & Reel Books, 2010; $16.95 softbound.

Fly Rod & Reel magazine has just released a second collection of fly-fishing stories. The first, published in early 2010, contained the cream of the winning entries in the magazine’s annual Robert Traver Fly-Fishing Writing contest. The new collection is culled from a larger group of pieces published in Fly Rod & Reel between 1998 and 2008. It includes fictional works by a group of arguably better-known or at least more widely read writers, including Charles Gaines and Robert F. Jones. Jerry Gibbs, the longtime fishing editor of Outdoor Life, has a piece in the collection, as do other names familiar to the hook-and-bullet press, Thomas McIntyre, Cliff Hauptman, Rob Brown, Dave Hughes, and Seth Norman among them. It’s a stellar crew, and their contributions are another reminder that angling writing can be serious, thought-provoking, humorous, even literary — a welcome respite from things such as “Hoppertunity Time!” “Mayhem in the Marquesas,” or “Soft Hackles For Hard-To-Catch Trout,” universally important though such works must be.

The new collection’s title implies that its contents are going to be about trout, but while that’s largely so, Rob Brown’s contribution, “The Old Masters,” is about steelhead, and both Jerry Gibbs’s “Ironman” and T. Felton Harrison’s “Nobody Has to Know” are set on Florida saltwater flats. That’s bait-and-switch of an innocent sort, I suppose, since I’m guessing the word “trout” appears in the collection’s title to appeal to as broad an audience as possible. I won’t make any conjecture about “love story.”

In truth, Dave Hughes’s sly and clever tale about a success-obsessed angler, a cooperative guide, the client’s wife, and an assistant guide, “Love Story of the Trout,” gives the collection its title. Hughes, by the way, is alone in having two stories in the collection. “What It Was,” an amusing fable about a logger’s accidental discovery of fly fishing, is the second. Hughes writes for Fly Rod & Reel, and perhaps that’s why there are two pieces of his in the collection. Either that or editor Joe Healy figured out that Dave writes about twice as many angling essays and books as anyone else in the game and gave him his statistical due. My own favorites in the collection are those by the late Robert F. Jones and by Cliff Hauptman. Jones, in case you’ve not encountered his writing, was a longtime contributor to Sports Illustrated and Field & Stream, a writer of very good books on dogs and on African hunting, as well as the author a handful of rather bizarre novels. Jones’s “The Dead Man of Windigo Brook” is something of a fable, a ghost story of the sort you might read aloud around a campfire to a bunch of Boy Scouts. Or Girl Scouts. It’s a spine-tingler in the classic American style of Poe or Washington Irving.

Cliff Hauptman, whose work one rarely encounters anymore, wrote a number of how-to fishing books, as well as a series of short pieces about an over-the-top character named Dog Nose that ran in Gray’s Sporting Journal a bunch of years ago. Those stories were consolidated into the novel The Dog Nose Chronicles. Dog Nose surfaces again in “Meyer the Fly Tyer” as he and his partner seek to gain some notoriety for their guiding business by inviting a famous fly tyer to fish with them. Meyer, a master tyer, caster, and angling strategist, turns out to be a 75-year-old Hassidic Jew, and his arguments for the proof of God’s existence center on the torments encountered while fishing. Enjoyable stuff.

California Fly Fisher’s Seth Norman (or does Seth now belong to the world?) is present with “Hobard’s Gate,” a classic Norman tale of justice served in which the straight shooters gain their revenge over the impolite, nefarious bad guys.

John Gierach pens the introduction to the collection and briefly addresses the definition of “sporting fiction.” At just two and a half pages, his piece is no reason to buy the book, but at $16.95, Love Story of the Trout is nonetheless a great way to pass a couple of hours. I give it three flies out of five on my totally biased rating scale.

D. C. Ounty

The Never-Ending Stream: A Tribute to Fly-Tying Form and Function

By Scott Sanchez. Published by Pruett Publishing Company, 2010; $34.95 softbound.

Many fly fishers, perhaps even most, never think about the antecedents of the flies they fish, or the rationale underlying each pattern’s design, or, perhaps just as importantly, how that design reflects the designer’s experience and even personality. Behind each fly, however, there’s a story, a history. Scott Sanchez, a professional fly tyer and fly-fishing guide, realizes that we are all beneficiaries of the expertise and inspirations of those who have come before us and that these form, in essence, a river of converging concepts and experiences — The Never-Ending Stream of his book’s title. “While I have a reputation as an innovative flytier,” Sanchez states in his introduction, “my patterns wouldn’t exist without the ideas and help of others. We all build upon the past and present to achieve our current set of ideas.” Sanchez’s angling experience revolves primarily around the waters of the Intermountain West (he’s originally from Salt Lake City, Utah, and now lives in Livingston, Montana), so it’s hardly a surprise that the flies he prefers and the designs he creates reflect a regional character. Or, stated a little differently, his flies reflect the characters of the region, as well as a few from beyond.

Each chapter of The Never-Ending Stream profiles a fly tyer who has had an important influence on Sanchez’s own angling and tying, along with a recipe and photographs of one or more of that tyer’s iconic fly patterns. Included are: Boots, Joe, and “Little Boots” Allen ( Yellow Humpy, Double Humpy, Rubber Leg Double Humpy); Dan and John Bailey (Dark Olive Mossback, John’s Elk Hair Hopper); Johnny Boyd (Lightning Dart All Purpose Chub Minnow), Charlie Brooks (Montana Stone), Jay Buchner ( Jay’s Dry Stone Fly, Dun Caddis); Jack Dennis (Bleeding Hart Kiwi, Amy Stone); George Grant (Black Creeper); the Rene Harrop family (Harrop Hairwing Dun); George Herter (Spey Fly); Randall Kauffmann (Kauffmann’s Golden Stone Nymph and Stimulator); Lefty Kreh (Lefty’s Deceiver); Gary LaFontaine (Emergent Caddis Pupa); Mike Lawson (Henry’s Fork Hopper); Craig Matthews (X-Caddis, Sparkle Dun); Franz B. Pott; (Sandy Mite); Bob Quigley (three Quigley Cripple variants); Rainy Riding (Rainy’s Prototype Foam Beetles); Shane Stalcup (CDC Parachute Dun); Doug Swisher (Madam X, without and with parachute); and Al Troth (Troth Shrimp; Troth Elk Hair Hopper).

Clearly, these are patterns that have much utility on California’s freestone streams, spring creeks, and lakes (several of the flies even originated here), but the value of The Never-Ending Stream extends beyond that of mere pattern reference. Sanchez helps us understand why these patterns were created, which improves our own approaches to solving the problems that lie behind the design of every fly. And by focusing on the designer, he not only pays respect, he gives these flies additional color — background to the story that we create when we fish them. I only wish the artfully composed photographs had better resolution (they are, however, good enough to tie from).

Richard Anderson