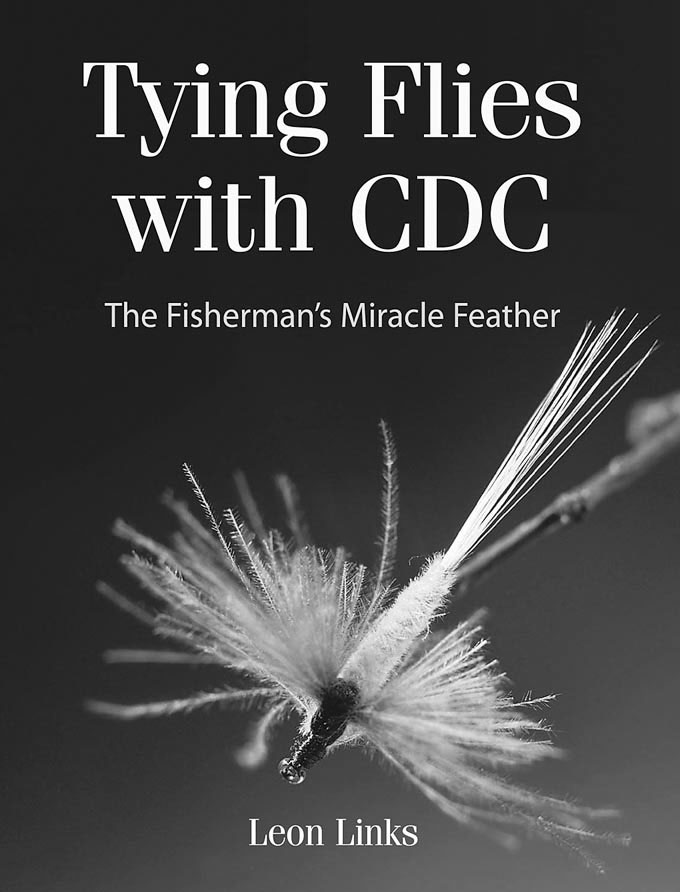

Tying Flies with CDC: The Fisherman’s Miracle Feather

By Leon Links. Published by Stackpole Books, 2010; $24.95 softbound.

Water-repellent duck-butt feathers known as CDC (cul de canard) have become increasingly common in fly patterns created in the United States, thanks to the efforts of advocates such as René Harrop. It was in Europe, however, that the potential of the material for tying fishing flies first was recognized and developed, and the name most commonly associated with its promotion has been that of Marc Petitjean, a Swiss. In Tying Flies with CDC, first published in England in 2002 and republished here by Stackpole, Leon Links, who is based in the Netherlands, both examines the historical development of CDC flies in Europe and, in step-by-step how-to photos, illustrates techniques for creating many of the most important original patterns. He also includes brief contributions by numerous fly tyers in Europe, the United States, and Japan, with recipes for and photo spreads or how-to photos of their most interesting flies and techniques.

The feathers from around the preen gland at the base of a duck’s tail were being used to tie fishing flies as early as the 1920s in the Swiss Jura mountains. Research by Marc Petitjean, whose interest in CDC goes well beyond the entrepreneurial, discovered a style of fly called a “Moustique” in that part of the Jura, tied by Maximilien Joset and Charles Bickel in towns about 60 miles apart. These classic CDC flies resemble wingless Catskill dries, but have a CDC feather wound around the shank where a cock hackle would be. Rather than propping the fly up in stiff barbs, the CDC moves and gives life to the fly.

Variations on that style gained more widespread recognition after World War II. French professional tyer Henri Bresson coined the somewhat sensational name “cul de canard” (“duck’s ass” is a reasonable translation), but such PR moves aside, the uses for CDC and the techniques necessary to implement those uses really began to expand in the 1980s. A Slovenian tyer and angler, Marjan Fratnik, frustrated by the fragility of Moustique-style CDC flies, developed the F Fly, essentially a down-wing, caddis style application of CDC feathers at the eye of the hook over a thread body. And in the mid-1980s, the German magazine Der Fliegenfischer published articles on making dubbing-loop CDC hackles by Gerhard Laible and Robert Pfandl. In Germany, the technique became known as Pfandeln, “Pfandling,” a term that for obvious reasons of homophony never caught on here in the English-speaking part of the forest. (“He fondles his flies.”) In 1993, Laible published CDC Flies, the first book devoted exclusively to CDC, and he is recognized as one of the leading proponents of the material, but as I noted, the major popularizer of CDC material and its best-known innovator of tying techniques and tools has been Marc Petitjean, who has developed everything from midge patterns and emergers to streamers and steelhead flies.

The Fratnik and Laible/Pfandl techniques, with CDC tied down on top of the hook shank or inserted in some sort of thread loop, perhaps using the split-thread technique developed by Marc Petitjean, remain the foundations of tying flies with CDC. The tyers from around the world whose patterns and recipes Links documents, however, have pushed the envelope in a variety of interesting ways, and as a catalogue of what can be and has been done with the material — that is, as inspiration for when you’re sitting at the vise with a particular problem of imitation to solve — there’s a lot to like here. The flies tied by Japanese tyers Ryo Shimazaki, Mingsugu Bizen, and Nori Tashiro are particularly stunning, as are the extended-body spent mayflies and midges by French tyer Jean-Louis Teyssié.

Indeed, my principal grump about the book is that there often are no how-to step-by-steps for these and other interesting (although admittedly complex) ties. For the same reasons that CDC is attractive to fish — it’s supple, it’s gossamer barbules give an impression of movement and life — CDC isn’t the easiest material with which to tie. You’re basically tying little bits of air surrounded by fluff to the hook, and it can be hard to manage. The how-to sections are useful, but as with most techniques, gaining some experience helps.

The flip side of that is that you can do things with CDC that no other material allows. I just tied some variations on a Petitjean mayfly emerger pattern, and they are incredibly buggy. CDC has other downsides, of course, including the propensity to get slimed (Hans van Klinken, of Klinkhåmer fame, even has an emerger pattern called Once and Away — “One and Done” in Americanese), but that’s why Shimazaki invented Dry Shake. If you want to know what has been done and what others are doing with CDC, go to the source — Tying Flies with CDC.

Bud Bynack

Holding Lies

By John Larison. Published by Skyhorse Publishing, 2011; $24.95 hardbound.

John Larison’s new novel, Holding Lies, shares the same setting and a few of the same characters as his first novel, Northwest of Normal. We’re once again in the fictional southwestern Oregon community of Ipsyniho, through which a river of the same name flows and from which a growing band of fly-fishing guides make their meager livings.

Larison’s Ipsyniho River is modeled closely on the North Umpqua, even to the point of giving some of the Ipsyniho’s holding water the same names and putting the real person who monitors the North Umpqua’s Steamboat Creek in the same position on the Ipsyniho. It’s an interesting mix of fictional invention and reality.

Like the North Umpqua, the Ipsyniho suffers from familiar problems: declining runs, overfishing, and friction between fly fishers and conventional-tackle anglers, between the old guard and newbies, and between those who would protect the river and those who would exploit it for glory or profit. All good grist for the novelist’s mill.

Holding Lies is the tale of fly-fishing guide Hank Hazelton’s difficult journey into the repercussions of past decisions. Twenty-six years earlier, he abandoned a marriage and a child to stay on the river as a steelhead guide. Now almost sixty, he’s faced with justifying the choices he’s made and answering important questions. What’s the value of a life devoted to steelhead — to fishing and fighting the good fight for their habitat — if living it causes you to lose the people you care about most? What kind of ethical compromises can be justified? What’s the price of a second chance?

Add a visit by Hazelton’s estranged and now grown daughter, a troubled love affair with a smart, but cautious woman, the death, perhaps by murder, of a hotshot young guide, the accelerating frailty of an aging mentor, and the inevitable tensions within a community that’s part Grateful Dead and part George Strait, and there’s a lot to drive a narrative.

Larison, via Hazelton, goes into considerable detail laying things out. And if the novel slows down at times while Hazelton agonizes over whether and how he’s really made a sorry mess of his life, it always comes back around to one or another of the main characters taking action to move things forward.

It’s got to be anything but easy to write a novel about steelhead fishing, or fly fishing, or any relatively esoteric activity with its own language and customs, for that matter. If you consciously limit your audience to people who know the sport, you’re going to bring up issues and use terminology that the uninformed may not comprehend. Go the other way, explain things in detail, such as why steelhead are so damned important to some of us or how a cast is made or a fly is tied, and you risk overstating what’s obvious to those already in the know.

It’s a fine line to straddle, and Larison doesn’t always succeed. The effect is that the experienced fly fisher may feel lectured, rather than led, while the uniformed are occasionally going to have moments of profound “Huh?” What, for example, is that unexplained thing called a D loop? And what are those numbers Hazelton uses to describe fly rods? Do they mean something? (“Oh,” thinks the Informed, “he’s fishing Kerry Burkheimer Spey rods. Cool.”) But when Larison does succeed, as in Hazelton’s explanations of how a good guide, who does it over and over, week after week, handles client expectations without becoming too jaded or losing his own love for the fishing, he does so astonishingly well.

There are also a few little things that rankle: Larison loves the word “oar” as a verb. Yes, I know that’s sanctioned by the dictionary and may even be common usage in southwestern Oregon, but it still sounds ignorant when I read about someone “oaring” a boat. And then there’s his reference to a Val Atkinson image of a guy casting off the wing of a wrecked plane in the Caribbean as “a famous Sage poster.” The name of the rod company that produced the poster does begin with an “S,” but it’s Scott. OK, puny gripes, but they’re distracting.

So, gripes aside, did I enjoy the book? Of course I did, and you probably will, too. There’s a fine story at the novel’s heart, characters who are easy to care about, and a wealth of intelligent commentary about the importance of steelhead. I simply wanted the novel to be better than it is, because I’d love to see something like it cross over from the tiny fly-fishing market into broad readership, get turned into a movie, and encourage multiple thousands of the unwashed to care about our rivers and our fishing. Just so long as they don’t actually take up steelheading. Things are already crowded enough.

Larry Kenney

No Shortage of Good Days

By John Gierach. Published by Simon and Schuster; $24.00 hardbound.

This started out as a review of John Gierach’s latest book, No Shortage of Good Days. It also turned out to be a review of Amazon’s e-book reader, the Kindle. I’ve had the Kindle for several months and love it. It is lightweight, easy to read, has amazing battery capacity, and most of all can store hundreds of books between its faux covers. In short, it is convenient and efficient.

So far, though, the books I’ve downloaded are either technical works or fast-paced whodunits that can cut through the din of airport noise. Technical books are read from point to point as the need arises, and the whodunits are typically so poorly written that even when you miss a chapter, you still get the idea. No Shortage of Good Days is the first book I downloaded with the intent to savor.

John Gierach is hands down the most popular fly-fishing writer alive. His first few books reinvented the Me and Joe genre, but with a fly rod. His quick wit, turn of a phrase, and ability to see the common things with an uncommon eye made him my hero. I read Trout Bum, The View from Rat Lake, and Dances with Trout each in a single sitting. Every few pages, I would laugh out loud.

I don’t think I laughed out loud at any time during No Shortage of Good Days. These are the same Gierach first-person essays about common events in the fishing life. They are told in the same unpretentious and lighthearted manner as his previous pieces, but they simply didn’t connect with me. Much of the writing seemed forced, as if he were writing for a deadline and needed to hit a certain word count.

Many of the pieces could have easily been trimmed and would have been better for it. One essay, however, “Firewood,” was perfect. He writes from the heart, and even if I didn’t laugh, I did crack a few smiles. I can imagine the words effortlessly flowing from his fingertips for this story about collecting wood, meeting friends, and fishing through few a cold weeks in February.

As always, I was impressed with Gierach’s ability as a wordsmith, and many times I reread a paragraph just to let his words sink in again. Saying this book isn’t as good as Trout Bum or Dances with Trout is more of a nod to how incredibly good, fresh, and original those books were, rather a statement about how poor this book is. A “poor” book by John Gierach would be considered a masterpiece by most other authors. On the way home from camping (where I read the book), we stopped at a store that had the paper version on the shelves. I began skimming an essay I had dutifully read on the Kindle and in short order let out a laugh. There was something in there I hadn’t felt before.

The Kindle may be too convenient and efficient. Perhaps something is lost in the move from paper and ink to plastic and electricity. Perhaps the Kindle can capture the words of a book, but somehow miss its soul.

Ralph Cutter