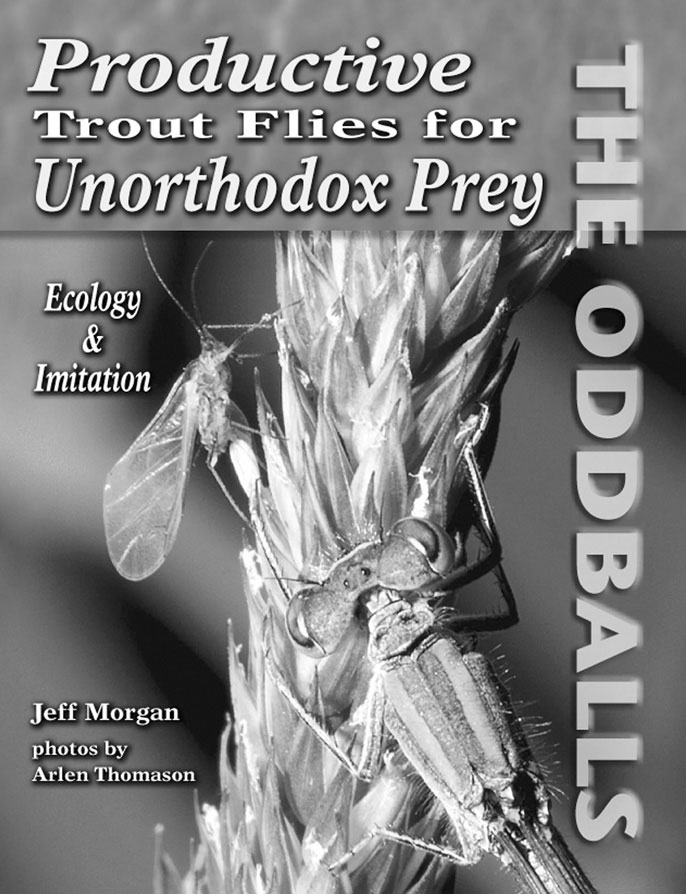

Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey: The Oddballs

By Jeff Morgan. Published by Frank Amato Publications, 2012; $29.95 softbound.

All trout fishing is local. The introductory chapters of Jeff Morgan’s Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey serve as a welcome reminder that former House Speaker Tip O’Neil’s dictum about politics applies just as well when fly fishers try to catch fish by imitating the foods that trout are eating. Morgan doesn’t mean that in some general way, different waters produce different characteristic hatches — damselflies at Lake Davis, for example, or the October Caddis hatch on the upper Sacramento. He means that all trout fishing is local in a radical sense: what’s happening here and now may not conform to any general conception of what “should” be happening on the stream or lake you’re fishing.

Many anglers have encountered situations in which they stumble into a hatch of one kind of aquatic insect while their partner fishing around the bend is into an entirely different hatch — or no hatch at all. Morgan’s argument is that such situations are not exceptional, but rather are the norm, while the notion that there is “a” hatch that is “on” during a span of time on any given stream is the result of a series of factors that contribute to generalizations that blind anglers to what’s actually right there in front of them.

That lesson is the one I’ll most remember and put to use from Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey.“You can observe a lot just by watching,” as the philosopher Lawrence Peter Berra once pointed out, and I’m convinced that being alert to the possibilities of what’s going on right now, right here, on the stream in front of me, not what I’ve been told to expect, and being prepared to deal with what I actually encounter there will improve my angling success.

What’s that got to do with “unorthodox prey” and “oddballs? And what’s so new about rolling rocks and seining riffles, looking for what critters are present where you’re fishing? Morgan argues that we don’t, in fact, always register what’s right there in front of us and that as the scientific literature on what trout eat shows, what’s right there often are overlooked foods that can form a major part of the diet of the trout in a stream or lake at particular times, in particular places, and under particular conditions. Just as in the history of angling with a fly, caddisflies were overlooked while fly fishers focused on mayflies, and stoneflies were given short shrift for a long time, there are a host of critters that, at the right time and in the right place, trout like to eat better than what’s supposed to be hatching and that anglers therefore ought to try to imitate: in alphabetical order, ants, aphids, baitfish of several species, beetles, black flies, centipedes and millipedes, chironomids, crayfish, crane flies, damselflies, Daphnia, dragonflies, grasshoppers, horse flies and deer flies, honeybees, leeches, mosquitoes, moths (as inchworms), net-winged midges, phantom midges, scuds, aquatic snails, sow bugs, and waterboatmen and backswimmers.

“Bu-bu-bu-but . . . lots of these are well covered in the angling literature!” I hear you say, “And I even have boxes full of ant and beetle and damselfly and hopper and leech and crayfish and baitfish imitations!” Right, and that’s one reason why I emphasized the general point about all angling being local. Because what Morgan has to contribute, even if you already fish imitations of a lot of these trout foods, is detailed information about the particular times and places when and where it makes sense for you actually to take them out of your boxes and fish them, plus the details of the behavior you need to imitate at those particular times in those particular places.

He does not expect you to abandon your boxes full of mayfly, caddisfly, and stonefly imitations and start carrying only black fly, centipede, and crane fly patterns, but he does suggest that being prepared for what you actually can encounter when fishing — and being aware that you almost certainly can encounter such “Oddballs” — is worth the effort. The mission of the book, he writes, is “to explore the best way to imitate the Oddball insects that slip through the cracks of traditional angling entomologies.” It “targets those situations where the ‘usual’ and ‘easiest’ tactics fail.”

What interests Morgan are niches, ecological and temporal. “Despite the local essentiality of these prey items,” he writes, “they are discounted by angling entomologies when looking at the ‘average’ trout diet. However, anglers don’t fish for ‘average” trout. We fish for individual trout, and those individual trout on individual waters regularly feed on one or more of the Oddballs.” Fish exist in microhabitats, not in some homogeneous environment, and so do the critters they eat. If it seems that “the fish aren’t biting,” he argues, it’s probably because what they’re interested in eating and what we care about showing them to eat aren’t the same, and blaming the fish for that gets things backward. Yet we continue to use “what works” out of habit, or what works on blue-ribbon waters, even if we’re blue-collar anglers fishing for blue-collar fish. We also follow fads and trends in flies and presentations, and when we do try to find out what critters are in the water and maybe being eaten by trout, we do so in a haphazard manner and draw hasty conclusions that would make a rigorous empiricist blush. Meanwhile, the trout eat what’s safe, easy, and locally abundant, regardless of what we think they’re doing. As locavores, they put even Berkeley foodies to shame.

Jeff Morgan’s previous books are Small-Stream Fly Fishing and An Angler’s Guide to the Oregon Cascades, and he clearly has put in his time on the water, not only observing a lot just by watching, but actively searching out what’s there and testing the ideas laid out in Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey. He also has a Ph.D. in history from Stanford, and like a good academic, he has approached his topic through the library, as well, reading the scientific literature on what trout actually eat, when, and where. As a result of that emphasis on scientific research, the book is salted with some eye-popping numbers concerning the prevalence of certain critters in trouts’ stomachs in certain places at certain times.

For example, “In a study of Eagle Lake in California, ants made up 42% of the total food items ingested by trout” when the study was done. Or about black flies: in the McCloud River, black-fly larvae “were the most consumed summertime prey among large, two-plus year old rainbow trout.” Conversely, “After reviewing hundreds of professional trout diet studies, I am convinced that grasshoppers are little more than a novelty item in the diets of most trout,” and one study found just one hopper in the stomach samples of 143 summer-caught fish. Consequently, he thinks hopper imitations are best just used as dolled-up strike indicators. Further: “based on all the samples I’ve located, a liberal estimate for leeches in the diet of the average stillwater trout is a paltry 2–5%,” although he says they’re nocturnal, so less likely to turn up in daytime surveys, and trout still desire them when they can find them.

There’s thus quite a bit of interesting information scattered throughout here. He notes that smaller baitfish are the usual prey items, although predatory trout prefer the largest ones they can handle, and that from midsummer through the fall is the best time to fish baitfish imitations, when “young-of-the-year fish abound.” And by “smaller baitfish,” he means really small, in some cases, noting there’s a two-to-three week window during which young scuplins “drift” with the current to disperse the newly hatched population and that sparse Muddlers, size 16 to 18, are the fly to fish during that temporal niche. For beetles, he notes that there are so many different kinds, it’s crazy to limit yourself to size 14 imitations or thereabouts and that imitations down into the 20s and as large as size 4 will bring fish to the fly when the more common sizes won’t, because fish have seen too many flies of the size usually used. For chironomids, he stresses the importance of exactness in imitation and suggests some interesting ways to achieve it. There are photos of suggested flies and fly recipes for all the critters covered, and while most are pretty straightforward, some, as in this case, are interesting for the way they implement the “Thoughts on Imitation” that’s one of the recurring subheads in the text.

And so on — as I said, there’s a lot of information here. I suspect that like me, most readers will likely to take from Productive Trout Flies for Unorthodox Prey things associated with the ways they already fish — in my case, looking for new opportunities, new times, places, and ways to fish beetles, baitfish, chironomids, leeches, scuds, and imitations of the other more usual trout fare — rather than going out and fishing imitations of some of the odder oddballs. Daphnia — tiny freshwater crustaceans — may constitute a genuinely overlooked trout food, “a whopping 68% of the diet of Pike’s Peak Cutthroat trout,” according to a study by Robert Behnke, and imitating an organism three millimeters long may present an interesting tying challenge, but the little freshwater krill feed and are fed on at the surface chiefly only at night and in low light, and during the day, you have to fish your attempts to imitate them down deep in the water column, from 15 to 35 feet. That may be where the trout are, too, at that time of day, but I’d rather watch paint dry. And as with studies that show that wine/coffee/chocolate and a host of other things are both good for you in moderation and bad for you in any amount, it’s sometimes hard to know how to take some of this. If you’ve read this magazine for any length of time, let alone for the whole 20 years, you’ll have seen columns by Ralph Cutter covering many of the same critters that Morgan discusses, and in some cases, at least, if I recall correctly, he’s come to different or opposite conclusions. Ralph has observed a lot just by watching from the trout’s point of view, under the water, and I tend to tilt in his direction when things I’ve read here don’t fully jibe.

But Morgan does convince me that it’s not enough to stride up to the stream with what you confidently believe is the right fly, the hot fly, the fly that worked before, or even the fly you always fish because you have confidence in it. We often say that we fish because it brings us out of ourselves and into the world around us. That can happen only if, like the trout we seek, we fully inhabit the places where we stand. That means caring about what’s here, now. All trout fishing is indeed local. Finally, while I’m reluctant to mention such things, the book would have been a lot more accessible if it had passed under a firm editorial hand. There is repetition, there are cross-references to things not said, there are cross-references to patterns not presented (he mentions a beetle pattern he calls “George,” but the only ones covered in this series are “John,” “Paul,” and “Ringo,” there are lots of grammatical howlers (“Commonly called ‘Daddy Long Legs,’ ‘Mosquito Eaters,’ or ‘Mosquito Killers,’ few of us have given much thought to crane flies’), and there are occasional misspellings that even a computer’s spell checker would have caught. Jeff Morgan clearly put a lot of work into this book, and he deserved better.

Bud Bynack