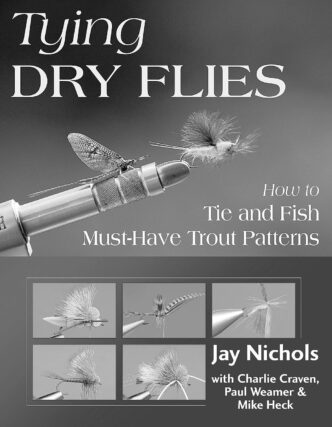

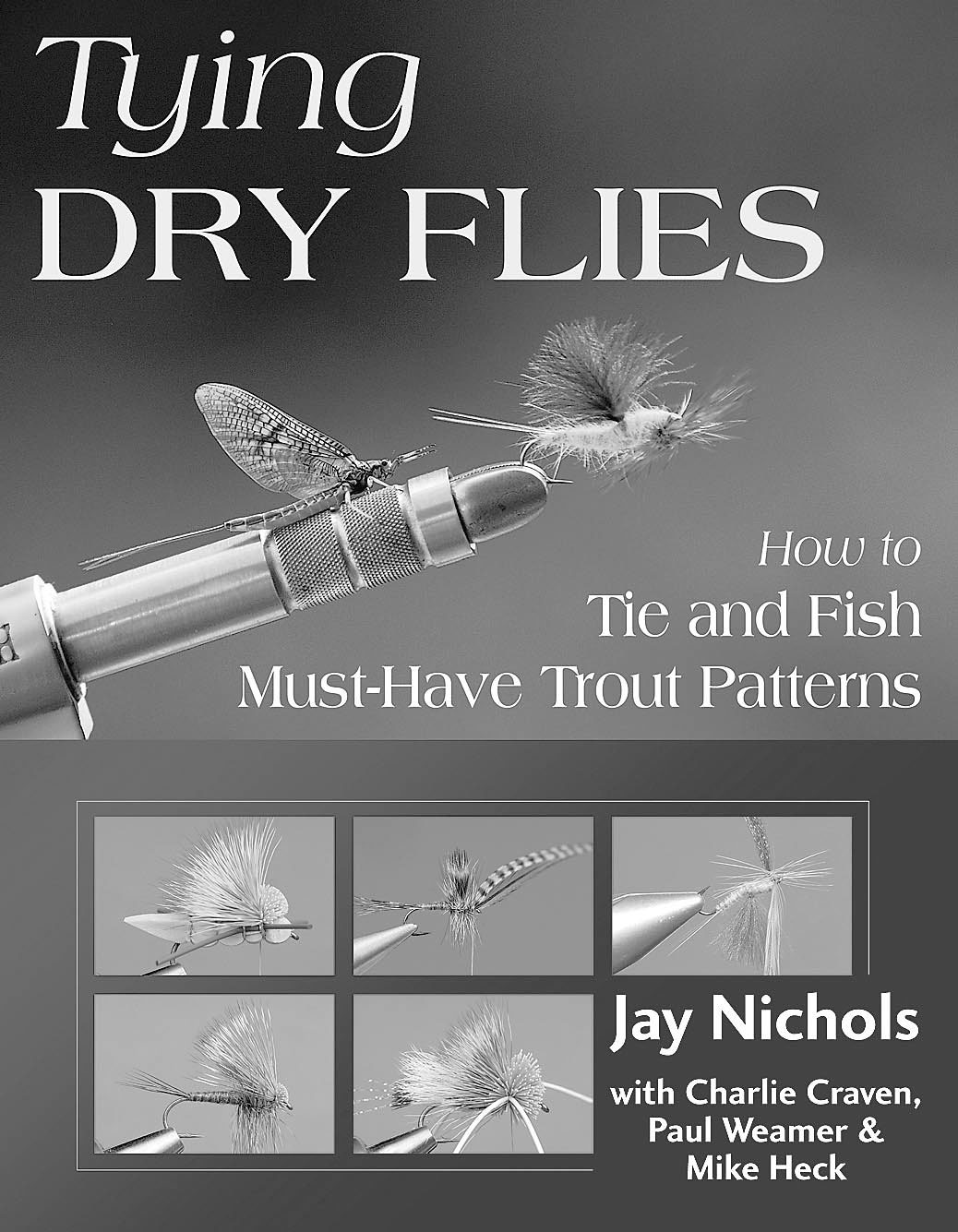

Tying Dry Flies: How to Tie and Fish Must-Have Trout Patterns

By Jay Nichols, with Charlie Craven, Paul Weamer, and Mike Heck. Published by Stackpole Books, 2009; $24.95, spiralbound hardcover.

Collections of “must-have trout patterns” often strike me as equivalent to “greatest hits” albums, a dying music genre once the staple of late-night TV and still encountered on PBS pledge drives (“The Greatest Doo-Wop Hits of All Time!” “Psychedelia: Nostalgia for Those Who Claim to Remember the Sixties!”). They tend to be a grab bag of what’s been overexposed or better forgotten.

Not so this collection assembled by Jay Nichols. It’s more like a mix tape, or rather, now that we think we’ve transcended the crass material world of tapes and CDs, a playlist — a collection thoughtfully assembled with the intention of bringing together diverse elements to produce an overall experience.

The patterns that he covers and the order in which he presents them seek, first, “to provide a basic immersion in traditional techniques.” All tyers need to know how to wrap a hackle so that it’s perpendicular to the hook shank, for example, and while that’s a basic skill, it ain’t always easy. As any baseball coach or casting instructor will tell you, basic skills and techniques require effort to master and continued efforts to retain and improve them. Nichols therefore includes classic patterns such as the Quill Gordon, as well as the Adams and Parachute Adams, the Griffith’s Gnat, Art Shenk’s Letort Hopper, the Elk Hair Caddis, and the basic Fur Ant and Parachute Ant.

But he also wants to “introduce readers to essential concepts in fly design,” and a lot of the patterns that he includes are indeed designs, not ties intended to imitate a single species of insect. These are some of the most interesting patterns in the book. They include Paul Weamer’s Truform flies, which pursue the implications of Vincent Marinaro’s concern for the visual impression exhibited to trout by a mayfly on the water. Weamer ties a parachute hackle under the eye of a specially designed Daiichi hook whose shape imitates the posture of a mayfly on the surface film. Also, there’s John Barr’s Vis-A-Dun, which, as the name implies, is designed for visibility and also for durability. And there’s Charlie Craven’s Charlie Boy Hopper, which illustrates both the intelligent integration of synthetic and natural materials — a major trend in contemporary fly design — and an elegant, economical approach to the use of materials and the development of tying techniques. The book begins with a chapter on practical fly design, and virtually all of the patterns that the volume covers, including the classics, illustrate aspects of good design in one way or another.

Nichols includes a number of what are now “mainstream” patterns that are meant to “represent as many different styles as possible” and that are indeed “styles” of dry fly, concepts that can be used to imitate many different species of mayfly, caddisfly, stonefly, or terrestrial — although stoneflies get short shrift here, being covered mostly by attractors that are sort of stoneflyish. These mainstream patterns include René Harrop’s Hairwing Dun series, a Swiss Army knife among mayfly imitations that can be tied for most species and modified on the stream to accommodate a variety of water conditions and stages of the hatch. They also include the classic hair-wing, no-hackle Sparkle Dun and the CDC Comparadun, the Foam Beetle, the Humpy (tied with foam), the Stimulator, the Turk Tarantula, the X Caddis, Hans Weilenmann’s CDC and Elk, and the Quigley Cripple.

All of these are proven patterns (the Quigley Cripple is my go-to fly during and after a hatch), and all are relatively simple to tie — the Turk Tarantula perhaps being the exception. And Nichols values simplicity in fly design, including, as well, some simple emergers by Craven and Weamer and a basic Trico spinner. Taken together, that list of flies would stock a series of fly boxes with dry flies that would be effective anywhere that trout are found. These patterns also traverse pretty much all of the techniques that a contemporary fly tyer would need to master in order to tie effective flies. And because the step-by-step tying instructions are often contributed by the coauthors, that is, by Craven, Weamer, and Mike Heck, as are some of the accompanying texts, there frequently are neat little tying tips embedded in the instructions, as in Craven’s advice about how to form the underbody at the head of a Stimulator, which, if not done right, can literally produce a slippery slope down which all the effort put into the fly slides to disaster. These guys have thought long and hard about fly tying, and it shows.

Finally, there are suggestions about how and why to fish these patterns, including creating a Smashed Caddis — an X Caddis with a wing that you’ve smushed down with your thumb so it splays out and imitates a spent caddis. That sure beats tying the complicated spent-caddis pattern I used to fish. (Ever try to create a tightly packed spun deer-hair head on a size 14 fly?) In the immortal words of Homer: “D’oh!”

All these aspects of the book are valuable in their own right, but the overall experience conveyed by the diverse elements of Tying Dry Flies is a sense of the state of the fly tyer’s art with regard to the dry fly, circa now. Nichols is a former managing editor of Fly Fisherman magazine and the fishing-titles and submissions editor at Stackpole Books, and parts of this text are collected from that publisher’s excellent back list of tying books. In that sense, too, it’s a playlist. As a collection, it brings together in a cohesive whole the diverse elements of classic and modern dry-fly design and tying techniques. It would make a great text on which to base a tying class or for any tyer interested in the current state of the art.

Bud Bynack

Moving Water: a Fly Fisher’s Guide to Currents

By Jason Randall. Published by Stackpole Books, 2012; $24.95 hardbound.

It was cold, dark, and raining a few evenings ago when this book arrived. The wood stove was almost glowing, and the faint pops of rain against the window and soft slumps of smoldering firewood made a nice backdrop to a glass of wine and a quiet read.

Only a few pages into the book, I found myself idly flipping through it, looking at pictures, and then my eyes wandered over to the laptop, and I wondered if maybe an e-mail had arrived. Moving Water: a Fly Fisher’s Guide to Currents is definitely not a light fireside read. It is a textbook.

The bibliography of the book contains no fewer than 90 dissertations, treatises, and scientific papers on hydrology, fluid dynamics, and fluvial geomorphology. If this makes your eyes glaze, read no further. If you want to learn about currents, however, break out the highlighter, a pencil, a pad of paper, and a pot of strong coffee. For you, this book is a dream come true. As Lefty Kreh writes in the foreword, “You’ll have to read and reread it many times to fully absorb its contents.” Moving Water has a vast amount of information crammed into 200 pages without much fluff between the words. The author starts by addressing the “lotic ecosystem” and how rivers work. He builds a solid foundation and understanding of waters and watersheds without really providing any information that will add to an extra hookup. I like this kind of stuff, so I found the read to be enjoyable and enlightening.

At about a quarter of the way into the book, it delves into currents, laminar versus turbulent flow, and the effects of deposition and erosion. It is here that the author introduces the concept of vertical drag, as opposed to the more commonly addressed horizontal drag that we deal with on every cast. Vertical drag occurs when the leader cuts down through disparate currents which cause the nymph to drift unnaturally. Until the very last page of the book, vertical drag, and how to deal with it is a key theme. (Spoiler alert: vertical drag can be mitigated by mending upstream, slowing the drift, then adding slack, or by adding weight).

Chapter six describes the “benthic community,” which is the population of living organisms in the water, and how its various constituents are shaped and driven by currents. Chapter seven is much the same, but deals specifically with how trout and salmon behavior is influenced by currents. The final and unfortunately the shortest chapter, if you are looking for angling tips, is titled “Fishing Strategies.” The chapter describes how to fish three different scenarios: drop-offs, midstream obstructions, and sweepers.

Most people will not read Moving Water cover to cover, but instead will use it as a reference from time to time. The index is excellent, and my copy of the book is already dog-eared. The photos and illustrations (all black-and-white) are simple, but effectively convey the information.

Ralph Cutter

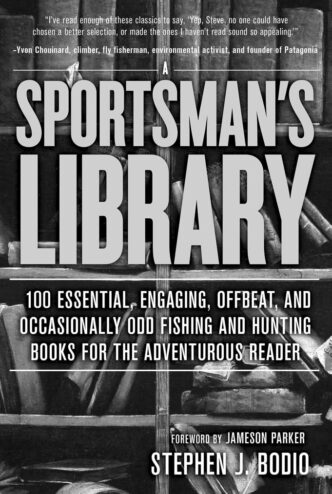

Fishing Classics Revisited

A Modern Dry-Fly Code

By Vincent C. Marinaro, published by Crown Publishers, 1950, 1970.

When it comes to books dealing with stream insects and trout fishing, I feel a bit like the little girl in the adage who had to read her book report aloud in class. “This book,” she said, “tells me more about penguins than I care to know.”

So I might be the person least qualified to comment on Vincent C. Marinaro’s A Modern Dry-Fly Code — and not just because I fish with only five flies.

But I don’t hesitate to call the book a masterpiece. There is certainly something to be said for the things we do when passion strikes, and passion certainly struck Vincent Marinaro on the banks of Letort Spring Run, at one time the most famous limestone trout stream in America.

Vincent Carmen Marinaro was born in 1911 in western Pennsylvania — and during his lifetime, he rarely found any reason to fish outside of the Keystone State. He lived for most of his adult life in the little town of Mechanicsburg, in the Cumberland Valley in south-central Pennsylvania, and he fished all the nearby spring creeks in that famous region of limestone waters. But it was the Letort that owned his soul. He was in many ways a “one-river” author. But in that river — a creek, really — he found the entire world. Marinaro was more than just a maverick angler and fly tyer. He made his living as a corporation-tax specialist, was a classically trained violinist, and — if you believe everything you read on the Internet — was even said to be able to speak up to 10 foreign languages, a claim of which I’m a wee bit skeptical. I mean, how many foreign languages can a man master and yet never leave the Cumberland Valley? Marinaro designed his own bamboo fly rods, and he taught himself to become a world-class stream naturalist and bankside photographer. He enjoyed cooking and dining on Italian food and smoking cigars — but even more, he relished a good argument. Marinaro was highly opinionated — he could be very stubborn about flyfishing matters, often refusing to back down — but he was always “old school” in the way he conducted himself and in his sense of what constitutes proper decorum on-stream and off. A great respecter of fly-fishing traditions, he broke all the rules. “Brilliant” and “irascible” were the words most frequently used to describe him by both friends and enemies alike.

Above all, Marinaro was a writer’s writer. A Modern Dry Fly Code could have been written by the author of the Georgics. And a reader comes away with the feeling that despite the book’s title, Marinaro would have preferred to have lived in an earlier century. Paul Schullery, author of American Fly Fishing: A History, has said no other angling work of its era can match Marinaro’s book “for sheer originality and literary style.” Marinaro brought to his fine literary sensibility — and to his subject matter, which was the close study of insects and feeding trout — the same seriousness of purpose and scrupulous attention to detail that he must have brought to poring over the Pennsylvania Tax Code.

A Modern Dry-Fly Code was published in 1950 to rave reviews and utter indifference by readers. The failure of his book wounded him deeply. But it was republished in 1970 — and he lived long enough to see it enter the canon. In fact, he saw his innovations adopted by fly fishers all over the world. These days, what fly anglers everywhere take for granted are solutions to problems originally worked out by Marinaro at his fly-tying desk or during the countless hours he spent on the banks of Letort Spring Run, patiently studying the different ways that trout were rising to floating insects on the creek’s slow and weedy currents.

In his landmark book, Marinaro showed how anglers could extend their fishing season in the dog days of summer after the major mayfly hatches were over. He was the first to stress the importance of fishing terrestrial insect imitations during these months — and the need for strict imitation of the land insects that would fall into the water. He also introduced the idea of fishing miniscule flies — what he called “minutae” — to imitate the vast flotilla of really teensy bugs that made up the greater biomass of insect life on the creek.

Marinaro’s major contribution to the art of fly tying was the introduction of the so-called “thorax style.” He moved back the wing of the fly on the hook, tied the hackles in a way that wouldn’t obscure the wing, and split the tails quite vividly to increase stability.

That’s standard stuff today. And more about penguins than I care to know. What really stood out for me were the descriptions of the limestone creeks and the angling. Once upon a time, the Cumberland Valley must have been a kind of fly fisher’s Arcadia. And it was apparent that even while Marinaro was writing his book at midcentury, that pastoral world was on its way out.

Today, Letort Spring Run flows through the ugly suburban sprawl of Carlisle. Pesticides and siltation from cress farms and construction from nearby commercial development have decimated the mayfly hatches on the Letort and on other Pennsylvania spring creeks. Letort anglers cast their flies into a limestone ditch smelling of honeysuckle and mud while listening to the whine of a nearby freeway. Marinaro did not intend for his book to be an elegy to a lost way of life, but that is clearly what it has become.

In “A Backward Look,” the introduction to his breakthrough 1970 edition, Marinaro acknowledged to his readers that he had been somewhat “provincial” in his outlook at the time he wrote the book. He wrongly believed that a limestone stream such as the Letort had no counterpart anywhere in the world except the chalk streams of England and France. “I did not know then as I know now that many similar waters — rich, weedy, full of insect and fish life — existed elsewhere and are particularly numerous in the Midwest and West.”

Whether our spring creeks in the West go the way of Marinaro’s beloved Letort is written on the wind and running water.

Michael Checchio