I first heard of Tehipite Valley many, many moons ago, long before California became my home and long before I became a “serious” angler.

At the time, I was living in Houston, Texas, a city devoid of mountains and valleys but frequented by hurricanes. Though I grew up playing street basketball outdoors in the balmy heat, I in no way fit the conventional description of an “outdoorswoman.” It was Bernard Yin, an avid outdoorsman and angler, who spoke of this obscure place and who, over the years, became my partner through everything.

Tehipite is the Mono word for “High Rock,” and Tehipite Valley is regarded as the most remote valley in the Sierra Nevada. It is situated on the Middle Fork of the Kings River as well as in the middle of those other more recognized names: Kings Canyon and Yosemite Valley.

Bernard journeyed there in 2006 with his fishing buddies, a group of adventurers who euphemistically dubbed themselves “The Black Diamond Trout Society.” I learned that Tehipite is an extremely secluded valley, essentially untouched by humans because of the arduous trek in and out on an iffy trail, but it was as dramatic as anything he’d ever experienced. The payoff was pristine streams of rainbows and browns, hidden waterfalls and petroglyphs, plus a monumental dome, all virtually to yourself. The idea of it blew my raw mind. Tehipite: the far-away illustrious valley. I was determined to experience it.

BECOMING AN ANGLER

Intriguing as it was, I had nil experience backpacking in the mountains or anywhere really. If I were to reach this mythical place I’d need to prepare well, so I asked Bernard to take me along on his fishing jaunts to become better acquainted with the settings of his tall tales. He graciously accepted my request (this meant he could go fishing, y’all) and began showing me the ropes.

Or lines, rather. Blue lines on maps, leaders, tippet—he patiently demonstrated the details and knowledge required to become a fly fisher. Truthfully, tying knots and securing a fly to the end of the line was of minimal interest initially, but I was definitely game for the pursuit. What I vividly recall and relished most at that time were the mountains—the ravishing rocks and their receptive streams where those lovely trout lived. The majesty of these enormous landforms was revelatory for me, a petite woman who grew up modestly in the hood. I was humbled, and I loved it.

More trips to California meant more trips to the hills, and when I married Bernard and moved to L.A. in 2014, I expected these expeditions would be a mainstay in our lives. It was most delightful crawling up canyons and rock hopping up rivers, if not for a healthy fear of rattlers. As a lifelong athlete, I appreciated the provocations of exploring new territory, taking greater risks to possibly enjoy greater rewards; I was never disappointed. Handling the fish was less of the goal, though we all know the tug is the drug, and I valued the catch-and-release ethos. A worthwhile side effect of fly fishing is observing ecosystems and habitats, consequently becoming an immersed student of Mother Nature.

In addition to sharing intel, Bernard shared his fisher friends, and their encouragement during those first years validated the role of the angling community in personal growth. The SoCal legend Chiaki even built a custom rod for me, and I honed my skills over the decade. One could and would now describe me as a proper adventurer. I’d hauled myself to some of the gnarliest locations in CA to seek wild and native trout, respectable training grounds, and was primed to finally arrive at the mythical place.

THE PLAN

Our group of seven planned our trek beginning on the Fall Equinox, and put in a few miles after picking up our permits in Prather before camping for the night and completing the descent into the valley the following day. We’d spend two full days fishing the Middle Fork and Crown Creek, investigating the Gorge of Despair, and basking in the Valley’s seclusion before embarking on a two-day return ascent. Six days, five nights. The two full days in the valley would allow for exploratory excursions, each destination offering its own lessons, presenting impressive points of views and perspectives. We often joke that we live “risk-adjacent” lives, be it pushing on another mile or around the bend with the well-intended “what-if?” and this was no different.

THE TEAM

Our esteemed team included Bernard and recently retired Matt on their triumphant Black Diamond return 18 years later. Noah, a Boy Scouts troop leader, grandson of the author of THAT fly fishing book-to-film adaptation, and “designated dad” joined us from SoCal. Our beloved, wild, Midpines-man David—fly fishing guide and owner of Yosemite Outfitters—added his two high-school climber buddies, Brett and Jenn, accompanying us fresh off of the PCT. A highly experienced crew with trust bursting at the seams, plus a small arsenal of emergency locator beacons because you never know. Fifteen years ago, I would definitely have been voted “Least Likely To Be Here.” However, I’d prepared myself well in the way women often work harder than their peers to accomplish the same task, training all year to ensure I wouldn’t be the one dragging the group back. Indeed, I was ready.

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

After years of fantasizing about this fabled place, at last Bernard, Noah, and I departed L.A. early-ish to collect our permits before the station closed. We opted for a last-meal pizza, and I FaceTimed my parents a final farewell, quickly shooting out texts to loved ones before losing signal and making my way off of the grid. The group agreed to rendezvous at the trailhead in the mid-afternoon, where we put the final touches on our packs and we were off! The elevation at the trailhead was about 7,200 feet with the dusty trail peaking just shy of 8,600 feet. We chatted for a few miles and chose a level enough site near a small stream just off of the trail. There was an enthusiasm and anticipation in our talk on that crisp evening. After stargazing and expressing our hopes and expectations for the days ahead, we retired to our tents. We set off the next morning and trekked 12 miles of poorly maintained trails—over burn scars and dozens of felled trees, through white thorn bushes, robust shrubs, and swarms of face flies—to reach the rim’s vista.

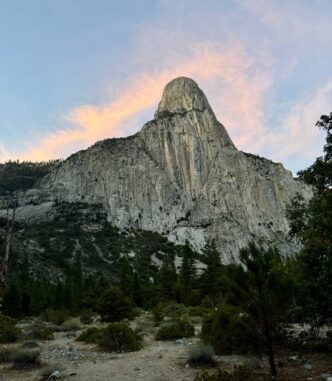

There we stood breathless, as the first clear sight of the valley revealed Tehipite Dome, the largest granite dome in the state. Over 3,500 feet of dominating rock, isolated but not unreachable. Taller than El Cap and fuller than Half Dome; a dirtbagger’s mecca. The mighty Middle Fork below appeared more a glistening brook from that height. What this sacred place lacks in accessibility it makes up for in grandeur and the sublime, and it is worth every step.

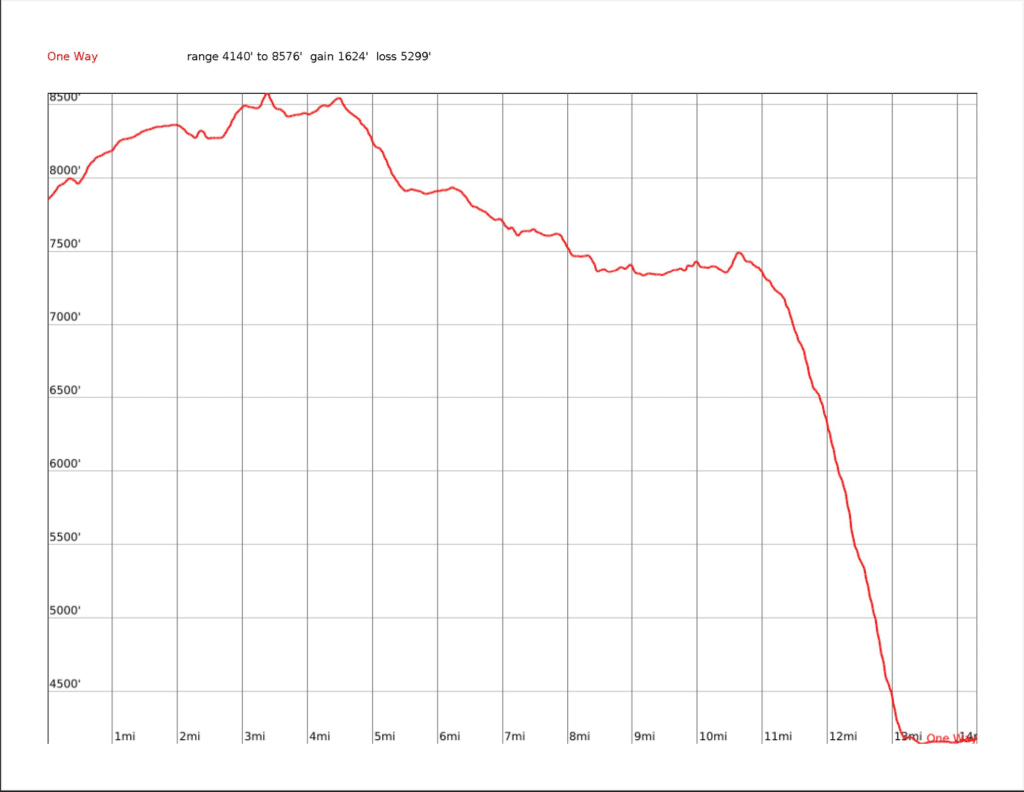

Profile of the steep descent into the valley—and ascent out!

And there were definitely more steps. From the surreal lookout, it was only an approximate 3,000 feet over a 2.2 mile descent to our base camp. The CalTopo graph of this stretch demonstrates a masochistic drop before it flatlines, and one has to question their sanity. We feasted our eyes, snacked, and continued onward. We overcame the descent with banter and the occasional motivating sight of the growing granite in the distance, scrawling mental notes to relay back to Tehipite veteran, Craig Ballenger, who regretfully couldn’t join. We’d later be informed upon our surfacing that he was, indeed, with us in spirit.

We kept our spirits up. My feet were killing me, and I was confident my heels and toes were blistered by the time we hit bottom (they weren’t). Surely, I had massively bruised my thigh from hurdling with my pack over yet more felled trees (I had). Some things one can’t quite prepare for as we continued to navigate through various plants, including thorny blackberry bushes snagging and scratching with every step. (Note: We did return to forage said blackberries, ripened impeccably for the most exquisite oatmeal known to humans.) We lumbered over more obstacles before our view at the edge of the forest was unobstructed, clearly seeing we had arrived. We threw off our cumbersome packs and called it home. Tehipite Dome approvingly overlooked our resting place, and the myth was realized.

THE VALLEY

The glacially carved valley is approximately three miles long and one mile wide. Dwarfing us was not only the colossal Dome itself, but a confluence of water on two sides, as well as manzanita and yucca surrounded by shady pines and oaks. No other humans in sight, just 360 degrees of rock walls and peaks, and endless possibilities. I caught myself staring up at that immense face, I couldn’t take my eyes off of her. I was awestruck, basically in disbelief that I’d achieved this feat. The sunset was befitting of our efforts, and we struck up a fire, conversation, and savored our dinners and company. Few things are more delicious than recovering around a campfire, swapping stories and catching up on life’s battles and victories with comrades beneath that stunning silhouette and stupendous starry sky.

But what was I doing here? Unlike explorers before me who were seeking gold, silver, and other resources to pillage, my ambitions were set on rainbows, browns, and a novel experience. In fact, before my first cast, we sniffed out the petroglyphs site which our two seasoned members expertly guided us to using only their 18-year-old memories. For me, biding one’s time to pay homage to the original stewards of this blessed space was non-negotiable. Frank Dusy “discovered” the valley and his party named it, but both Native people and Mexicans had lived in and explored it prior, so how does one discover something already known and experienced? I was merely a visitor, and I acknowledged my role: come, appreciate, leave no trace.

Jenn relaxed with a book while Brett bravely set out on a solo climb, and the angling cohort set out in search of resident trout. Weather conditions were nearly perfect; the water levels were safe enough to cross when necessary, temps were cold, and the fish were frisky. We experimented with dries, dry-dropper rigs, nymphs and indicators, completely sub-surface with streamers, and they all were reasonably effective. Nothing too substantial in size but not dinky in the slightest. Bernard, in his familiarity, knew browns were lurking, and he switched his game up to target them. Eyeballing undercuts and deeper runs with more heavily weighted nymphs or small streamers resulted in an increased ratio of browns. No trophies, but, again, no dinks. The abundant Middle Fork carried on for miles, and our eyes crept up the river, but it would have to wait until next year. A few of us investigated a gorge that we mistook as the aptly named Gorge of Despair. Bernard recalled fish and water up the wash toward the gorge from his previous trip, and accounts from climbers told of a large pool at the bottom of the gorge that sounded enticing to us anglers. David, who was paving the way barefoot, hollered a warning of an expressive rattlesnake. We cautiously scaled our way up without finding water, but what a sight to behold of our Granite Cathedral from our faux GoD! We fittingly claimed it “Gorgeous Despair” and were satisfied with our side quest.

To celebrate our first full day in the valley, we opted for trout tacos and tequila. I’d carried down an REI Nalgene of booze and a stack of homemade corn tortillas from my favorite taco shop, a true labor of love considering my pack weighed a third of my own body weight. Three of us decided to harvest a few fish before dusk, and Bernard nabbed one on a stimi with his first cast. Alright then, my turn. We spotted a riser downstream, and I let out enough line to deliver an elk hair caddis dinner directly to its mouth. Slurp, set, ding ding ding! We chuckled about how trite the entire scene was as I wrangled it in, but while marveling at the perfection of this specimen, a tinge of guilt arose, as it so often does for me. Deciding it was too large for our purpose, we released it to the Kings. Noah was upstream somewhere unknown, and we’d hoped he’d fill in the gap and our tummies by bringing a few to camp. To my relief, he did, and we dined triumphantly. Perhaps somewhere out in the river, that freed trout did as well. What a glorious night and suitable send off for David, Brett, and Jenn who would depart the next morning.

VALLEY DAY 2—HOOKLESS

Gusts of hurricane-esque winds battered my tent as I lay awake in our private valley. Feeling conflicted about tormenting a remarkable fish, I reassured myself that tomorrow, I would cast hookless flies under the judging gaze of that towering monolith. It’s an idea I had been toying with for months as I became more deeply involved in conservation activities. But to put in the sweat equity to arrive in this specific location and purposely choose to clip the hook off a flawless dry fly? That would demonstrate next-level commitment to my conservation cause. Commitment to the trout’s cause, especially. Despite this being a sequestered stretch of river, the heat of summer, drought, and fire affect all watersheds and their inhabitants. I didn’t fancy being another factor trout were up against when there was something I could do about it.

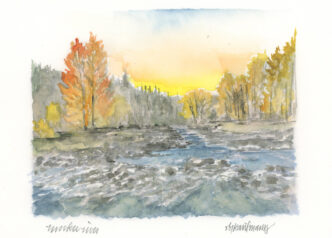

After breakfast, we crossed Crown Creek and trudged through the forest to enter the Middle Fork farther upstream. We rock-hopped and waded to where bows and browns welcomed us aplenty. We discussed how the fishing was good, but it wasn’t a “fish-on-every-cast” good. Considering the low pressure of anglers, we were puzzled. Nonetheless, in a single pool, I’d enticed six or seven trout with my hookless ant, each one eagerly attacking from their respective territories, unwittingly chomping at the same innocuous lure. True to my promise, I was giddily deceiving the fish without causing them stress. Their aggressive assaults were as equally entertaining for me as if I’d actually wrestled them to the net. While the fishing was fantastic, the crown jewel that day was Silver Spray Falls, the picturesque cascade of Crown Creek greeting the valley floor; 370 feet of water crashing down and adorning the base of The Dome. No telling how deep the rock was carved from the ceaseless force, but in an appeal to the bottom dwellers, we threw streamers and nymph-and-indicator rigs that were the trick for fooling footlong trout. Recalling from his 2006 expedition, Bernard shared, “I learned that the more miles you put in don’t necessarily equate to larger fish.” That bit of wisdom morphed the mission, and we turned our attention to the greater picture of simply being present in this privileged spot. We cast to our hearts’ content in the scenic pool, its generated breeze forcing us to sharpen our skills to land a dry fly for the optimal drift. After I submerged my full body into the shockingly frigid water, we munched on olives, crackers, and cheese, reveling in our surroundings. I picked up my rod for a few parting casts; my harmless Parachute Adams seduced a couple more trout and we all got a rise out of it.

THE ASCENT

The next morning, cleansed and rejuvenated from another nightly baptism of wind, we packed to embark on our ascent. Though I’d admired that epic granite rock more times than I care to admit during my short stay, I scanned her once more from the base at 4,100 feet to the tippy top at 7,708 feet, committing it to memory, forever grateful.

To keep our minds off the steep path ahead, we guesstimated how many downed trees we’d be clambering over. 50 seemed like a safe bet. Back through the thorny bushes and steep switchbacks, we conquered the 3,000 foot hill. Yips, squeals, and woohoos were exclaimed at the top as a hawk soared hundreds of feet below (I’m not making that up!) Forcing on in search of a water source for the evening’s camp with the rose-colored glasses of the journey’s beginnings now removed, our eyes keyed into the harsh reality of our surroundings. We found a less-than-ideal campsite before reaching Crown Valley, amidst an unsightly fire-damaged and bark beetle-ravaged forest. Rated “0 out of 10 Trees—Do Not Recommend.” Exhausted from the hike out, we called our day early. During the windless wee hours of the night, Bernard was awakened by the unsettling sound of a collapsing tree nearby. If you’re wondering about our gentle wager of blown trees we’d scrambled over, we stopped the official count at 115 part way along the trail. We agreed to safely underestimate the total at around 200.

Our final day on the trail was brilliantly uneventful as we traveled long stretches silently, immersed in our own thoughts and reflections.

MYTH NO MORE

There was plenty to ponder that day and beyond as the realities of the myth settled in. Honestly, I imagined an unflawed, wild wonderland, and while that was mostly true, there was evidence of human effects. The state of the forests was concerning; fires and beetles left portions of them eerily quiet. Why weren’t we hearing and seeing more birds? What do face flies do when no one’s there? The mammal situation, both small and large, seemed suspiciously sparse. We’d spied piles of bear scat, evidence they were around, but I never managed to attract them in defiance of Brick Tamland’s caution (if you know you know). A dozen or so squirrels and chipmunks over days and miles? Odd. Three water snakes surfaced, but a place known for its rattlesnakes and only one (thankfully) made its presence known? Hmmm. There were three deer near our cars, but that was the extent of it. For a little-visited area, we could be forgiven for expecting more. A huge appeal to the myth of Tehipite is how such a picturesque and cloistered destination still exists in California in 2025—ask most mountain enthusiasts, and they’ve never heard its name. Yet there we were, strange as it was, witnessing the effects of humans whilst being far from humanity. Climate chaos is no stranger, and we all must familiarize ourselves with answers and solutions.

THE JOURNEY CONTINUES

It has since become clearer how I got there and why. Though my childhood adventures were set far from Sierra soil, when I’m traversing her forests and sleeping on her floors, the scent of dirt transports me to the backyard of my mother’s childhood home. I am reminded of afternoons with my sister, charmed by the garden my grandparents affectionately nurtured on the outskirts of the inner city. My young imagination couldn’t have fathomed reaching a destination like Tehipite, but I fulfilled it. Does the success of a probing trek depend on what can be retrieved or harvested for my own gain? Gold, silver, or behemoth rainbows and browns? Am I casting my fly in vain if there’s no hook? Moving beyond barbless and breaking the hook off of the fly is my choice, and I consider caring for our creeks and creatures my responsibility. The trout’s effort is substantial enough to bend the rod, wrest the fly under, and I feel the fleeting weight of it before it releases. Do I connect less if I’m not reeling in “the trophy?” I am rewarded, the connection is complete. Besides, everything is ephemeral, right? I’m blissful, and that’s sufficient. I can hardly wait to return.

This put the “hip” in Tehipite.