The ratty Olive Matuka was probing along the edge of a side channel where the Owens River fingers out into Lake Crowley when the fly just stopped abruptly, and I reflexively snapped the rod tip up into a hoop. For about two seconds, I thought I’d snagged on the edge of the channel. Then the rod throbbed, the line cut away at an angle, and the fish surged out into deeper water.

R. G. Fann and I had found a two-track down through the sage on the west side of the Owens River and had been wading through Crowley’s shallow flats, standing up in our float tubes and poking along the edge of the channel until we stepped off the edge and could sit down in our tubes. There was a swirl farther out in the lake, and we had followed the channel through a serpentine curve. Then there was a swirl behind us, and R. G. had started casting toward that fish. I had worked out a cast toward the first swirl.

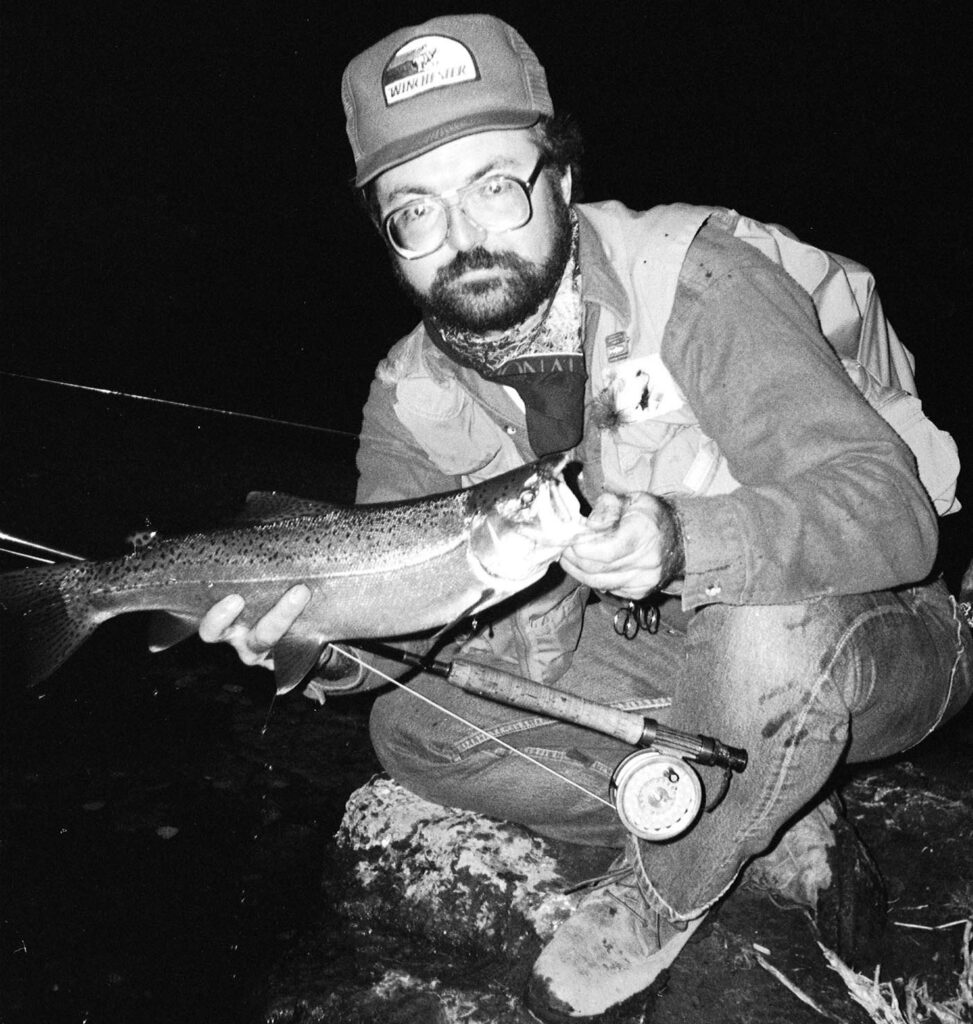

This was a long time ago, so I don’t remember if it was on the first cast I made on that late afternoon or after many casts, but when the Matuka stopped and the fish surged away in a deliberate and powerful run, I knew it was a sizeable trout. R. G. ended up next to me and was trying to wrestle the old Nikkormat from around my neck while I worked the fish back up to us. There is always some circus when we fish together.

When the trout finally tired and came up to the edge of my tube, we were speechless for a moment. R. G. said something profound, like, “That’s a big fish.” We rushed to get the fish released unharmed, but marked its length on R. G.’s rod. It was a fat, 23-inch brown trout. A fish like that probably weighs over four pounds. After it swam away, we might have made a few more casts, but the truck was half a mile away, and the evening was getting cold.

R.G. is pretty handy with a camera, but when you snapped the shutter in those days, there were a lot of uncertainties about whether or not you’d actually end up with a decent image. We were lucky, though. The photo lab didn’t screw up the processing of the TriX black-and-white film, the images were exposed correctly, and they were in focus. I think we were more excited when the photos came back than we were out there in the lake as the sun was setting. Looking at the old image, that fish still looks to me like it was a lot bigger. R. G. has a 16-by-20 print of that photo on his wall. It’s still the biggest trout I’ve caught from Crowley.

Crowley History

Lake Crowley was created in 1941, when the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power dammed up the Owens River at the mouth of the gorge and flooded a portion of Long Valley, creating a relatively shallow reservoir to store water to be shipped south for taps and swimming pools in Los Angeles.

A sizeable lake in Long Valley is not a new geological phenomenon. The Owens River filled this same valley, actually a huge volcanic caldera, starting six hundred thousand years ago, and the thousand-foot-deep lake that was there drained within only the last hundred thousand years, when the Owens finally filled the caldera and the lake topped its rim. The Owens River then cut the gorge, eventually emptying the lake and creating a large meadow.

In spite of what my boys might think, I never did fish the big lake before the Owens drained it, but I’ve fished Crowley since the late 1970s and have watched the evolution of this fishery and the fishing tactics used here. Crowley has always inspired creative approaches to angling. Lately, there have been developments that translate really well to other stillwater flyfishing venues — tactics that you not only can use to catch more fish at Crowley, but that you can take with you to other lakes and impoundments.

A Fish Factory

When it dammed the Owens, the LADWP inadvertently created what has become one of the best stillwater trout fisheries in the Western United States. The shallow flats hold an exorbitant number of aquatic insects, with midges, damselflies, dragonflies, and stillwater mayflies creating a food chain that grows trout quickly. Add in a healthy population of Sacramento perch, whose fry provide bigger morsels of food for trout, and you have an ideal trout-production facility.

The bulk of the trout in the fishery come from plants of subcatchable and fingerling trout from Department of Fish and Game hatcheries, usually to the tune of four hundred thousand to half a million fish per year, mostly a variety of strains of rainbow trout, but brown trout and cutthroats are becoming larger components of the plants. All the stocks are made in the fall, and the 4-to-6-inch rainbows usually reach 12 inches by the trout opener at the end of April, and most are pushing 15 to 16 inches by the end of the trout season in November. Those that make it to their second full year in the lake grow into fat 22-to-24-inch fish.

It wasn’t always this way. For years, Lake Crowley had a reputation with fishery biologists of being a black hole for rainbow trout. The DFG would plant the lake with half a million rainbows each fall, anglers would catch them by the boatload the next season, and then those fish would disappear. Trout not caught would never hold over more than one season. Rainbows over 16 inches and over one and a half pounds were almost never caught.

It baffled the biologists. The relative handful of brown trout planted in the lake in those years, through the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, grew to monumental proportions. Browns that weighed 10 to 20 pounds were caught each year — but never any quality rainbows. When the brown trout plants stopped (after the whirling disease outbreak at the Mt. Whitney Fish Hatchery that led to the destruction of the Whitney strain of browns), the Lake Crowley fishery consisted of pan-sized rainbows and a very few wild-spawned browns.

Then the DFG began experimenting with different strains of rainbow trout, and in recent years, cutthroat trout have been added into the mix. Even brown trout are being planted again.

The results have been nothing short of spectacular. Over the last several seasons, rainbow trout from three to five pounds have been caught regularly, especially during the late summer-fall special regulations season, when most anglers are catching and releasing fish. The biggest of these trout are mostly the Eagle Lake strain of rainbows in their third year in the lake. The cutthroats are still relative newcomers, and the brown trout are making a resurgence. As the cutts and browns continue to have a chance to age and more are added to the lake, the trophy component of Crowley is coming back. A number of brown trout over 6 pounds have been caught the last two years (the biggest trout on the opener in 2011 was a brown over 11 pounds), and cutthroats in the same size class have become a relatively common catch, even though many anglers confuse them with rainbows because they lack a defining red “cut” on their throats. Some actually may be wild cutthroat-rainbow hybrids that have been spawned in one of Crowley’s tributary streams, making accurate identification even harder.

Surveys done by the DFG in the past have shown that wild trout make up at least 25 percent of the trophy trout longer than 16 inches caught during the late summer-fall trophy trout season. This was discovered when the DFG was experimenting with different strains of rainbows to see which would survive for longer periods in the fishery. The DFG staff had the monumental task of fin-clipping all four hundred thousand rainbow trout planted in the fall so when the fish were caught, one, two, or three years later, they could be identified.

The DFG knows that 96 percent of the Coleman-strain and 90 percent of the Kamloops-strain fish are caught and kept by anglers within their first year living in the lake. But only 50 percent of the Eagle Lake–strain rainbows are caught that first year. The rest survive the fishing season and are present in the lake the next year as bigger fish. While the numbers get whittled down each successive year, some trout survive into their third year, and those are the whopper rainbows in the 22-to-24-inch range. They can weigh five pounds or more by late summer, after fattening up on perch minnows.

Through examination of fin clips, the DFG found there is a large trophy component that has wild origins. These trout come from natural spawning in the Owens River and the Convict-McGee drainage or the smaller, jump-across tributaries of Hilton Creek, Whiskey Creek, or Crooked Creek. The wild component could be multigenerational mixes of any of the rainbow and cutthroat strains that spawn that time of year.

Through cooperation with the LADWP and ranchers who run cattle on leased lands around Crowley, irrigation diversions are better monitored and screened, and far fewer of the naturally occurring fry are trapped in these diversions, helping even more survive and contribute to both the stream and lake populations of trout. Streamside areas have been fenced so cattle don’t degrade the banks, and the willows and other vegetation are coming back along the creeks, especially in the ConvictMcGee drainage, stabilizing the banks and making for better cover for the fish.

Thanks to a lot of hard work and effort by the DFG, LADWP, local ranchers, and lobbying by fly fishers to have sensible regulations (probably the most complex set of regulations on any water system in the country), as well as thanks to optimal management of this incredible fish factory, Lake Crowley has more trout and betterquality trout than at any time in my nearly 40 years fishing this system.

A Tactics Factory: Slam Dunks

In the same time frame that the fishery was being massaged into its current state, fly fishers were discovering this resource and developing tactics, gear, and fly patterns that work well on Crowley and subsequently on a lot of other waters, and for many species. The Crowley tactics can be divided into two periods and types.

During the early period, fly anglers learned to tie and fish perch imitations for trout. For a lot of seasons, in the 1980s and 1990s, the routine on Crowley, especially in the late season, was to hurl perch imitations on the outside edges of weed beds and along creek channels to entice the rainbows and browns. Crowley was where a lot of us learned how to fish streamers on floating, sink-tip, and full-sinking fly lines while wading the shoreline or kicking around in float tubes, which were themselves just catching on in popularity.

But there were still big vacant periods for anglers on Crowley, periods when the Matukas and Woolly Buggers didn’t work. If the trout weren’t eating midges or damselfly nymphs in the surface film or chasing perch minnows, they were a mystery. Where the trout went and what they were eating during the early season and the first half of the summer were question marks. Anglers would catch a few fish by deep nymphing and by stripping streamers at those times of year, but it was very hit-and-miss — usually miss. Most of us bided our time until the summer, when the perch minnows started congregating in the weed beds and bays and the trout were focusing on them.

There had to be more to Crowley than just the perch season and occasional days of surface activity, though. Everyone knew the trout were feeding throughout the year. It just took a little time for fly anglers to figure out what the trout were doing and how to catch them consistently. “Dunk” was a new word for me to add to my fly-fishing lexicon. As in, “We had 40 dunks for every three hookups,” or, “If you’re doing it right and it’s on, you get dunked every 10 or 15 seconds.”

Obviously, this is not about tall guys slamming basketballs through hoops high enough over my head to cause vertigo. It is about the latest tactic being used and perfected on Crowley.

In the late 1990s, local guides Harry Blackburn and Mike Peters “stumbled into the McGee Bay phenomenon.” Blackburn said. They’d walk down the mouth of the creek in McGee Bay, where hundreds of trout were stacked up, actively feeding — they could see the whites of their mouths as they fed. At first, they simply drifted nymphs down to the fish in the creek water still moving out into the lake, but as the fish spooked out to deeper water, the pair started fishing deeper and farther out. The first time they started using an indicator and a midge pattern, they were getting a strike within 10 seconds of the cast. Of course, they thought it might have been a fluke. But it wasn’t. The bite lasted the whole season. “It was just stupid, ridiculous. We were asking ourselves, ‘Is this illegal?’ How many fish can you catch in a day?” said Blackburn.

They started on the bank and graduated to tubes and canoes, then to john boats with motors. The stable craft allowed them to stand up above the water and see deep into the channels, where they could watch the hundreds of fish below. Both anglers ended up with boats and started taking a few select clients there. A pair of anglers could hook and land from 30 to 100 fish per day.

“It was a good year and a half to two years before the locals caught on to what we were doing, and then it just exploded,” said Blackburn. Today, there are fleets of boat, pontoon, and tube anglers fishing indicators with midges, nymphs, and even small streamers in deep water using this hot stillwater tactic. Hanging a fly under an indicator is not really a new tactic, of course, but it is used far less in still water and requires some specialized rigging and flies.

Blackburn says, “It’s such a simple method — but it ’s also ultracomplex.” While usually called “indicator midge fishing,” the tactic can be used with a wide variety of patterns representing midges, nymphs (especially damselfly and Callibaetis nymphs), and even young perch fry not much bigger than the aquatic insects. It consists of a leader made with a short and quickly tapered butt section of 3 to 4 feet with a 4X tippet 2 to 18 feet long or more, depending on how deep you are fishing. In water deeper than the length of your rod, you need to use a break-away strike indicator that will allow you to bring the fish close enough to land.

This rig doesn’t cast worth a hoot, but you are usually fishing fairly close to your float tube or boat, so distance casting isn’t important. Lobbing the rig out untangled is the critical factor.

When fishing midge larva imitations, most of the activity is very close to the bottom. While many guides have boats with depth finders, allowing them to determine the bottom depth precisely, Jim Reid at Ken’s Sporting Goods, in Bridgeport, who uses this same technique on Bridgeport Reservoir, says he finds the bottom depth another way. When in his tube or boat, he simply clips his hemostats on the end fly on his leader and lets them settle in the water until they are just touching the bottom. He then sets his indicator so the bottom fly in his rig rides six to eight inches above that point.

Two-fly and three-fly rigs are common for this type of midging, and there is no agreement among anglers on the best way to rig this multifly setup (see the sidebar on the next page). Almost everyone starts the rig the same way, by tying a fly on the end of the leader. Then they add pieces of mono or fluorocarbon tippet, tied either to the bend of the first hook or to the eye, adding the second fly to that piece of leader in the same way, then repeating the process if adding a third fly. The distance between flies is usually 12 to 24 inches, allowing for fishing at different depths and with different patterns.

Since midge larvae frequently hang vertically in the water, some anglers and guides believe the leader should be tied to the bend of the hook so both patterns hang vertically. But other anglers prefer that the fly sits cocked slightly off the vertical, because the larvae are often flexing through the water, and they tie from hook eye to hook eye, not from hook bend to hook eye.

While dead-stick presentations (no movement to the flies) frequently will work, especially if there’s a slight breeze putting a chop on the water, most anglers are constantly popping the indicator or throwing curves in the leader so the flies are moving up or down or through the water column like the naturals.

There is also no agreement about types of hooks or weight that should be used on the midge patterns. Some anglers believe in tungsten or other beadhead midge patterns to make sure the flies sink quickly, while other anglers prefer heavywire hooks to facilitate the sinking and allow the flies to “swim” more naturally.

There has been a massive hatch of new midge fly patterns in the last decade. Some are getting more imitative, while others are being designed for specific applications. Most Crowley anglers start with an Optima Midge and then go from there, with a wide variety of swimming, vinyl, and brokeback patterns gaining in popularity. Most anglers carry a range of colors, with black, grays, and dark reds the most common and with those that have a little sparkle or flash in the rib or head/gills preferred. As noted above, the multifly, deepwater indicator tactic can be applied with patterns other than midges, and at Crowley, the same rig is often used during damselfly hatches or Callibaetis hatches. Many guides are also fishing really small perch minnow imitations (one inch long or less) early in the season, when the fry are first emerging from the nests. Both the nymphs and the young minnows are relatively slow, deliberate swimmers, and adding a steady or stop-and-go retrieve helps trigger strikes. Just as with the earlier streamer tactics learned during Crowley’s “perch season,” the deep-water indicator-midging tactic is now being used for trout all over the Sierra and throughout the state on still waters. There are urban-lake anglers using midges for carp in city ponds and lakes. There are bluegill and redear fly anglers discovering the tactic for these big slabs. And I’d bet saltwater anglers will find a use for the tactic — in a slightly upsized form for bigger fish — around floating kelp.

Lake Crowley Guides’ Rigs

California Fly Fisher asked four eastern Sierra guides who use the indicator–deep midging/nymphing technique on Crowley and other waters to describe the composition of their typical setup. Most immediately complained there is no “typical” setup, because the depth of the water, its clarity, the time of day, the aquatic food being targeted, and the season all vary the routine, but they still agreed to play the game and give us some basic advice. Most noted that the deepest fly should be just 6 to 8 inches from the bottom for midging, with flies 18 inches to two feet apart above the bottom fly.

As the accompanying article notes, some of the guides, including Harry Blackburn (http://www.mammothflyfishingadventures.com or [760] 934-6457), who pioneered the deep-water indicator fishing at Lake Crowley, prefer fishing unweighted flies on heavier wire hooks to get the most action from their flies, while other anglers prefer weighted or beadhead patterns to get the flies into the strike zone quickly, relying on wave action for manipulation of the flies.

The guides surveyed here are Kent Rianda, David D’Beaupre, Jim Reid, and Tom Loe. Kent Rianda has probably put more fishing hours in on Lake Crowley and has studied the fishery more than any other angler. He will put in his three thousandth day on Crowley this coming season, and he has hours of underwater video footage of Crowley trout taking naturals and artificials. David D’Beaupre has adapted Crowley fishing techniques for use throughout the Sierra and on South American trout waters, where he guides each winter. Jim Reid spends most of his fishing time in the Bridgeport region, using the technique on Bridgeport Reservoir and other ponds and high-elevation lakes in this area. Tom Loe fishes throughout the Sierra, from Pyramid Lake in Nevada (where he was fishing and talking on his cell phone during our interview) to Bishop, using the indicator stillwater-nymphing technique all over the region, adapting it to different conditions.

As the article also notes, perhaps the most interesting differences in the way these guides rig their multifly rigs are in the method of attaching the flies to each other. Those who prefer the eye-to-bend arrangement, in which the leader is tied to the eye of the fly and a piece of leader is added on the bend of the hook, then the next fly tied on to this leader at the eye, do so because the midge patterns hang vertically in the water, mimicking a natural condition. Others prefer the eye-to-eye arrangement, tying both pieces of leader to the eye of the hook, cocking the fly more horizontally in the water, because the setup is perhaps more representative of a swimming midge. These anglers also believe that tying the leader to the bend of the hook hinders the hooking ability of those flies. Anglers should remember that California state law allows the use of only three flies, however you join them.

Rianda said his videos show that most trout take flies fished on an indicator rig while the fish are rising in the water column, so initial strike detection is difficult. All of the guides said that using a sensitive indicator and paying attention to its slightest movement is important. They all recommended striking immediately upon any change in the indicator. Ratios of strikes to hookups can be dismal for anglers who don’t pay close attention to their indicators, and waiting for the indicator to be pulled under frequently results in a missed fish. Days are measured not just by the number of fish caught, but by the number of indicator “dunks,” or how many times you were “rung,” in this type of fishing.

Kent Rianda

The Troutfitter, Mammoth Lakes, California

(760) 934-2517 or http://www.thetroutfitter.com

- Leader: A tapered nylon leader about half the length you intend to fish, with fluorocarbon tippet material to 4X or 5X added as needed to reach the desired depth. Kent fishes from 6 to 25 feet deep in Crowley.

- Indicator: Half-inch Styrofoam Corky, set with a toothpick or dental rubber band, “the more sensitive, the better.”

- Flies joined: Eye to eye.

- Number of flies: Three, up to five feet apart.

- Flies (size and pattern): Top fly, the platform, is the nonmidge pattern and varies throughout the year, starting with Callibaetis and damselfly nymph patterns early in the season, then shifting to perch and leech patterns in sizes 10 to 14 later in the year. The second fly is an attractor midge pattern, a larva or pupa, in size 16 or 18, with some extra color or flash. The bottom fly, “where you get 99 percent of your grabs,” is a size 18 (occasionally size 16 or 20, depending on water depth and clarity) midge pattern such as Kent’s Optimidge, a Red Baron, or a Shaft Emerger to match the insects present.

David D’Beaupre

Sierra Trout Magnet, Bishop, California

(760) 873-0010 or http://www.sierratroutmagnet.com

- Leader: A short-butt nymph leader with a total butt length of just 3 or 4 feet to facilitate sinking, with fluorocarbon tippet material of 4X to the top fly and between flies. The depth at which he fishes varies, but is usually from 12 to 20 feet.

- Indicator: Breakaway indicator that slides on the leader (Hendrix Indicator).

- Flies joined: Bend to eye (midges), eye to eye perch, damselfly patterns.

- Number of flies: Two.

- Flies (size and pattern): Midges in size 16 or 18 with a gray body and black rib or black body and silver or gold rib (Optimidge, swimming chironomids, or vinyl midge styles). Perch and damselfly nymph patterns, size 10 to 14.

Jim Reid

Ken’s Sporting Goods, Bridgeport, California

(760) 932-7707 or http://www.kenssport.com

- Leader: Depending on the depth at which the flies are fished, a standard tapered leader from 7-1/2 to 9 feet is the base, with 4X to 5X fluorocarbon tippet material used between flies. His fishing is usually focused in 6 to 10 feet of water in Bridgeport Reservoir.

- Indicator: Standard yarn, with a rubber-band stopper (Ultimate Indicators), or a breakaway indicator if you fish deeper than about 10 feet.

- Flies joined: Eye to eye.

- Number of flies: Three.

- Flies (size and pattern): The top fly is always a leech or damselfly nymph pattern in size 10 or 12. The second and third flies are usually midge patterns in size 16 to 18, but range from sizes 14 to 20. If Callibaetis mayflies are active, he sometimes uses imitations of these, rather than midge imitations.

For his midge flies, Reid likes the new hinged midge patterns, which have an extended body attached to a short-shank hook. The extended-body portion is tied on another hook shank (with the bend clipped off ) or on a piece of piano wire and then joined to the main fly with a loop of material, usually light mono, which is tied onto the body of the hook after looping it through the wire eye on the extended body.

Tom Loe

Sierra Drifters Guide Service, Bishop, California

(760) 935-4250 or http://www.sierradrifters.com

- Leader: Usually 15 feet or shorter, hand-tied nylon and/or fluorocarbon, with a 6-foot butt section of 0X or 1X, tapered to 3X, and then 4X or 5X fluorocarbon tippet of appropriate length for the depth.

- Indicator: Under-Cator (a Sierra Drifters product), sliding indicator if fishing deeper than 15 feet.

- Flies joined: Eye to eye.

- Number of Flies: Two.

- Flies (size and pattern): Broken Back Gillie (upper fly, midge pupa) size 18, Broken Back Tiger or Zebra Midge (bottom fly, midge larva), size 16. Small split shot added above the top fly.

Tom Loe’s “broken back” patterns can be viewed online at

http://sierradrifters.com/Fly%20Sales.htm.

Jim Matthews