The history of the United States is filled with harrowing tales of revolt, wealth, and competition — for better or for worse. One such story that has found a home in the pages of every middle school U.S. history textbook is of the California Gold Rush. Facilitating Westward Expansion in the mid-1800s, the Gold Rush brought Anglo settlers and their livestock to an area previously populated only by Indigenous peoples. As the settlers scoured the Sierra Nevada goldfields, their livestock overgrazed the flat plains and meadows that both held cultural significance to the Indigenous peoples and provided important functions for the ecosystem. Textbooks rarely mention the cultural consequences of Westward Expansion, and they often fail entirely to mention the environmental consequences.

Unbeknownst to the inhabitants of the Sierra Nevada at the time, there was something else of great importance residing within the rivers and streams: the golden trout. 10,000 years ago, volcanic flows isolated a few tributaries within the Kern River of the southern Sierra Nevada, causing golden trout to diverge from the rainbow trout lineage (See the “Forks of Kern Field Note” in the Summer 2025 issue). This new species preferred the cold, clear mountain streams in highly elevated meadows, adapting its scales to a golden color matching the stream’s decomposed granite. Over time, the golden trout, native to those few tributaries, were moved farther north by humans both accidentally and intentionally. The fish gained a 600-square-mile home range and flourished in their new habitats, garnering designation as the official state fish by the California State Legislature almost a century after the Gold Rush and earning its spot on almost every California angler’s bucket list.

Yet, this is simply where the story of the California golden trout begins. By the end of the 1900s, the long-term effects of Westward Expansion—habitat loss, over-harvesting of fish, hybridization with stocked non-native trout species—compounded by the growing impact of climate change, saw the trout populations begin to decrease. In the early 2000s, it was clear that the species would soon reach a critical level of concern, so a conservation strategy was devised by the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) to prevent the extinction of California’s state fish. A key part of that strategy was stream and meadow restoration, building on the Inyo National Forest’s legacy meadow restoration work that has been occurring on the Kern Plateau since as early as the 1950s.

IMPORTANCE OF MEADOWS

Although meadows only make up 1 percent of the Sierra Nevada landscape, they contain between 60-80 percent of its biodiversity. But, unfortunately, they’re not in great shape. Around 50 percent of Sierra Nevada meadows are degraded and struggle to perform their critical functions for the state’s water supply.

Healthy meadows act like a sponge by absorbing, storing, and filtering snowmelt from the mountains. The water percolates into the meadows and, during the summer months, the cooler, cleaner water is released downstream. In a degraded meadow, the springtime snowmelt simply runs off the landscape through eroded channels, effectively being lost instead of conserved. Healthy meadows even act as large carbon sinks, helping to decrease the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases. Importantly, healthy meadows provide excellent refugia for trout, with late-season base flows providing cold, clean water, cold-water refuge and camouflage from riparian growth, and complex habitat for all trout life stages. Degraded meadows lack all of this, adding to the California golden trout’s population decline.

GOLDEN TROUT PROJECT

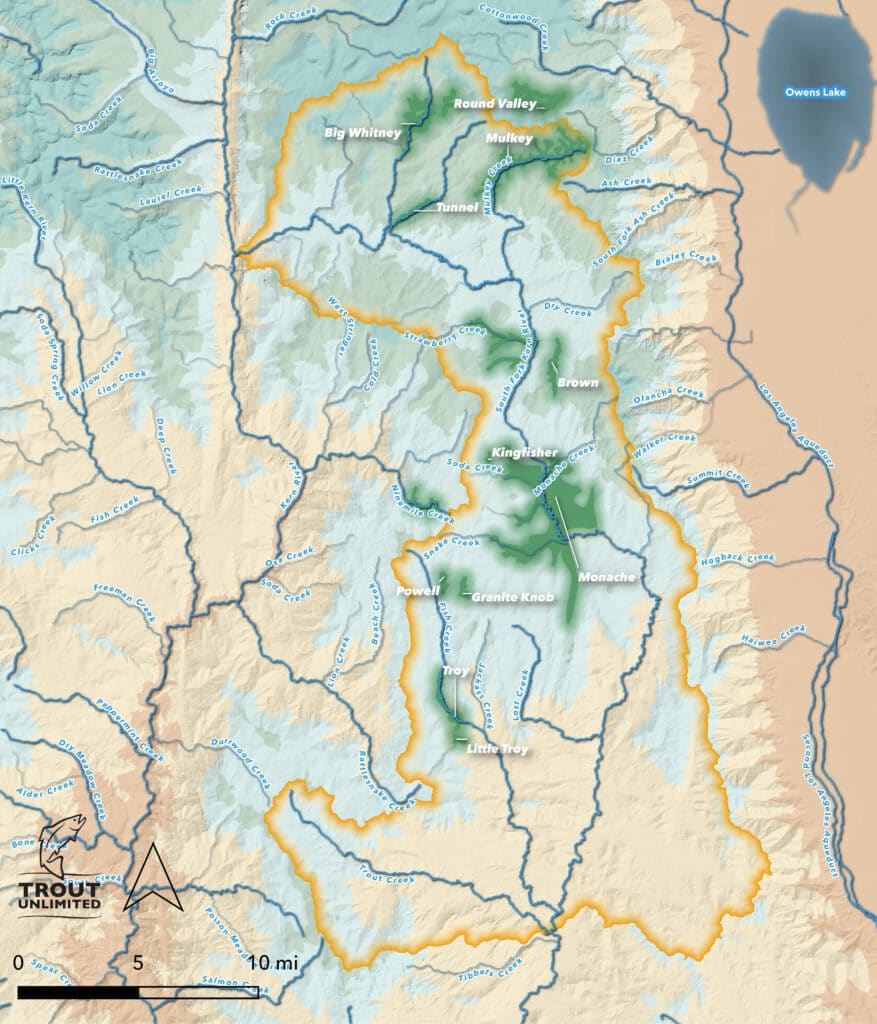

Trout Unlimited’s (TU) Golden Trout Project is responding by restoring meadows within the Sierra Nevada. Originating more than 15 years ago as a volunteer-run project, today the Golden Trout Project is a multi-partner, multi-million-dollar effort that has restored over 30 stream miles and 2,000 acres of headwater habitat in the South Fork Kern River Watershed, the California golden trout’s home range.

The primary goal of meadow restoration is to slow down and spread out the springtime runoff, so it has time to seep into the meadows. By using low-tech, process-based techniques, the Golden Trout Project focuses on reconnecting the stream channel to the meadow floodplain. The predominant restoration method involves inserting structures called post-assisted log structures, or beaver dam analogs (BDAs), into the streams to capture sediment and fill in the eroded channels. This prevents the water from rushing through and further eroding entrenched channels that course through degraded meadow systems. The BDAs create a physical barrier, causing the water to lose energy, spread out over the meadows, soak into the ground, cool the water, and increase the amount of water released in the summer months. For the California golden trout, that means more deep pools and cool water flowing into the late summer months, while stabilizing water temperatures during the winter.

TEAMWORK MAKES THE DREAM WORK

Jessica Strickland, TU’s California Inland Trout Program Director, identified the keys to the project’s success to date: “Strong partnerships and diverse support.” Long-term collaborations provide compelling stories to funding entities, Strickland elaborated, which made finding funding “extraordinarily successful.” TU secured the majority of its funding for planning through the CDFW. Strickland expressed gratitude, stating, “This work would have never kicked off the ground without their trust and willingness to make the first financial investment.”

The U.S. Forest Service is another key partner for the Golden Trout Project. With the majority of restoration efforts located in either designated Wilderness Areas, where no mechanized equipment is allowed, or remote National Forest areas with limited vehicular access, just getting to the sites required significant effort. All tools and equipment were trekked in on foot or carried by mules. Larger equipment was flown in by helicopter. Strickland expressed her appreciation for this partnership, saying, “U.S. Forest Service lands are managed for multiuse, and they have an overwhelming number of diverse projects on their docket. They chose to be champions for this work, and they didn’t need to. I am so grateful to all of the staff who initiated support and continue to be part of our partnership.”

According to Michael Wiese, the Inyo National Forest Watershed Program Manager, the Program’s achievements to date have exceeded the objectives outlined in the Inyo National Forest’s Land Management Plan (LMP). Signed in 2020, the LMP aimed to improve at least five meadows. Already, the Golden Trout Project has implemented meadow restoration work in 15 meadows. While those accomplishments are impressive, there is still much more to be done. TU plans to implement another 75 stream miles and 7,000 acres in-stream and meadow habitat restoration projects benefiting the California golden trout by 2030.

Elaborating on these partnerships, Gabriel Singer, Statewide Native and Threatened Trout Coordinator for the CDFW, stated “The key has been leaning on the strengths of each of the individual partners and working towards a common goal that we all passionately support: intact ecosystems capable of supporting resilient populations of healthy California golden trout.” Meadow restoration benefits many California native species, beyond the golden trout. Singer specified that restoration provides habitat complexity, “allowing species to carve out niches where they can thrive.”

MEASUREMENTS OF SUCCESS

The Golden Trout Project places a large emphasis on monitoring the meadows before, during, and for the decade following restoration to ensure that its goals have been achieved. According to Strickland, the monitoring program served multiple purposes. TU aimed to confirm that its restoration efforts were delivering the expected benefits, while also tracking any unintended negative impacts. A key focus was evaluating the effectiveness of BDAs to help design better-informed projects in the future. The program also established metrics for assessing instream aquatic habitat conditions, water temperature, riparian and meadow vegetation, streamflow, groundwater levels, and the presence and abundance of fish and macroinvertebrates.

The positive impacts of TU’s Golden Trout Project have extended far past the California golden trout. Tribes and communities within the Sierra Nevada support this project, and TU “hires up to 20 crew members every summer and implements a tribal youth work experience program,” Strickland said. These work opportunities are economically impactful, as resources and jobs can be limited in the area. Wiese mentioned that the project also has “a positive impact on the local tourism, as it brings in anglers and other recreationists into the area to fish for golden trout and enjoy the natural beauty that a proper functioning meadow system provides on the landscape.” Echoing Wiese’s sentiments, Singer reminisced, saying “you can’t replace the experience of catching one of these brightly colored fish with big parr marks, golden flanks, and red-orange bellies on a dry fly in a small stream running through a Sierra Nevada meadow at 9,000+ feet.”

Although the Sierra Nevada may no longer be teeming with gold, its land and animals are still worthy of great admiration and care. The Golden Trout Project brings together groups that highly value the protection of wild spaces and their inhabitants. While there is still more work to be done, TU’s efforts to protect California’s state fish, one admired by anglers and conservationists alike, emphasize the importance of restoration.