I’m zero for ten this winter on California rivers chasing winter steelhead. Ten days. Zero fish. If you know anything about steelhead, you know they’re already among the hardest fish to find. And I’ve made it even harder. I’m swinging flies for them.

Swinging is the bow hunting of steelhead. Sometimes it feels like more than that—like trying to lasso an elk that won’t knowingly let you within fifty yards. I could nymph. I could throw gear. You can stack the odds that way. I probably would’ve landed a fish by now—maybe several—if I changed methods. And I want to say this clearly: I have nothing against those methods. They work. I’d be lying if I said there aren’t moments when I want that. But that’s not the point. At least not at this stage in my fishing journey.

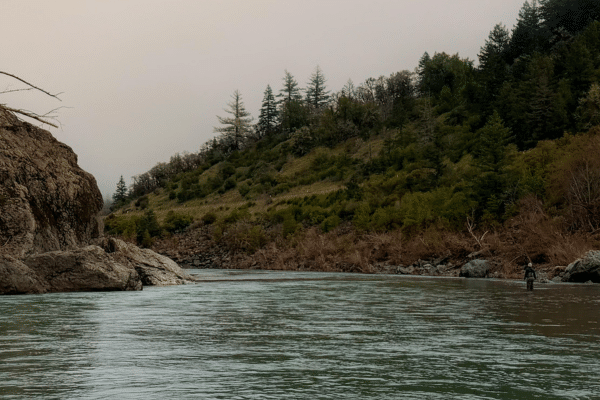

There’s something about casting across and down, taking a step, and doing it again that feels different, intentional. Like each swing isn’t just a cast but a quiet agreement with the river, one you’ve signed but don’t quite remember agreeing to. Swing and step. Swing and step. Covering the water like it’s a grid, trying to touch every square with a swung fly. It’s not efficient. It doesn’t always make sense.

There’s a strange belief that builds with each pass through a run—that every cast, whether touched by a fish or not, is pulling you closer. Not just by probability, but by purpose, as if some universal law were keeping count in a way I can’t see.

I’ve felt the grab before. I’ve landed a steelhead all the way in Idaho. And when it finally happens, it isn’t about triumph or ego. It’s an emotional unraveling. The connection to the fish, the friends you’re with, the river around you-it hits all at once. It’s overwhelming in a way that’s hard to explain to someone who only sees satisfaction in their fish count.

One of my relatives says he doesn’t understand why people stress about catching a steelhead. He believes if you’re fishing for them, there’s one out there for you—you just don’t get to decide when it’s ready. His dad hears that and says, “Well, that’s stupid,” as if we’ve mistaken stubbornness for spirituality, as if we’re trying to baptize our own obsession in cold river water. I can’t fully argue with him. There’s a thin line between reverence and rationalization, and I’ve probably crossed it more than once. Still, I keep showing up-not because I’m convinced this is part of some grand plan, but because something about the wait feels honest.

Some say horses produce an electromagnetic field, and when you stand near one, any false version of yourself falls away. I don’t know whether that’s science or folklore. But I think steelhead are similar, or at least I like to believe they are. Lately, I’ve been nervous about walking into the water, wondering whether they can feel my energy and slip away before I even get the chance to present a fly.

Maybe the fish aren’t testing my skill. Maybe they’re testing my alignment. The more honest I am with myself, the less I feel like I’m trying to conquer something. The more I feel like I’m participating in it. Maybe becoming a better husband and father makes me less of a threat to the fish that haunt these rivers.

Or maybe I just suck at fishing.