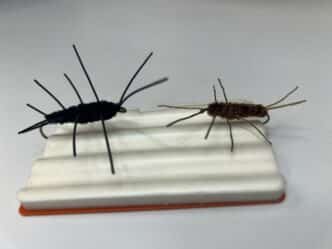

It was a warm spring afternoon, and the river ran deep and clear before me, a shelving riffle dumping into perfect holding water. Having waded into position, I began rummaging through my fly box for one of the spark-plug heavy stonefly nymphs perfect for scouring the bottom of this boulder-studded run. Long seconds later, my heart sank as I realized I had brought the wrong container—the only stoneflies in this box were some lightly weighted models I’d purchased years before and never used. I mean, why would I? There couldn’t have been more than six to eight wraps of lead beneath the chenille body, nowhere near the 30 turns I preferred to get bugs deep in fast-moving flows.

I knew without looking that my bag was without split shot—I’ve never been a big fan, feeling they create slack and dead spots in the nymphing rig that delay strike detection—so I was stuck with what I had. I lengthened my tippet and dropped from 3X to 4X in an effort to buy myself a bit better sink rate, but I knew it wouldn’t be enough. Tying the lightweight imposter on, I flopped it as far upstream as possible, raised my rod tip high, and began leading it through the drift (this was a long time ago, before indicators, when “high-sticking” was the favored technique). Halfway through, I noticed the nymph was actually visible a couple of feet below the surface, its sink rate overwhelmed by the tumbling hydraulics of the run. I remember sighing and giving up on the drift…

…just as a chunky, 16-inch rainbow materialized from nowhere and inhaled the fly.

Astonished by this unexpected event, I didn’t even have the presence of mind to set the hook, so it was only by dumb luck that the fish hooked itself. Landing the trout quickly, I was certain it had to have been a fluke, just one extra-aggressive trout amongst all the normal bottom huggers. Wading back out, I cast again…this time with the expected result. Nothing. Casting yet again, I half-heartedly raised the rod and distractedly watched as an adult salmonfly fluttered clumsily over the water a few yards downstream. It took a moment to notice I’d hung up on the bottom, and just as I began to try to yank it free, something in the back of my lizard brain registered that this new, lame fly was too light to have even reached bottom…and suddenly it was yanking back! Landing this cookie-cutter of the first rainbow, I felt something like an epiphany stirring in my previously closed mind. Was there a chance I’d been given a glimpse behind the curtain of the trout world? Could I be on the edge of something that challenged my deeply entrenched belief about the weighting of nymphs?

As it turns out, the answer was a resounding “yes”! Encouraged and excited, I began fishing again, this time with razor focus, and the results astounded me. Not only did I do every bit as well as with my heavier stoneflies, I was now able to fish holding water that had previously been too shallow and where I would have immediately hung on the bottom—which, of course, increased my hookups even more. At day’s end, I was flushed with excitement…I felt like I had been given a secret that would change the way I fished for the rest of my life. And it did!

What followed were months of trial and error, tying and fishing nymphs that were more lightly weighted than I was comfortable with, using them in water I would have previously thought was just too deep and/or swift. My eyes were opened as I began to realize that fish were often more than willing to move up in the water column to intercept a meal. In fact, I came to believe they are often quite accustomed to finding their food drifting well off the bottom. This blew my mind, a quantum shift in my traditional way of thinking. Most noticeably, this made casting large (now more lightly weighted) stonefly nymphs so much more pleasant and versatile, allowing me to also fish shallower holding water. I still sometimes had to add a split shot to the leader when fishing small nymphs in heavy water, which I didn’t care for, but shortly after, metal beads broke onto the fly-tying scene and solved that problem for me. Certainly, I still like to fish fairly deep in the water column—I’m just not nearly as convinced that I always have to be scraping rocks.

To be clear, for years I have used dry-droppers for much of my nymphing, and most of my observations reflect this. I will readily agree that a proficient Euro-nympher will hook more fish than I on any given day and that they typically fish quite deeply. I am amazed at the effectiveness of this technique and appreciate that it normally also avoids adding split shot to the system. I encourage anglers to fish in the way they enjoy and to always keep an open mind so as to learn from each other and the fish. For me, using dry-droppers, it was eye-opening to reduce the tippet length between the dry fly and the nymphs to less than the water depth and experience no fall-off in the number of grabs compared with my traditional tippet length of 1.5 times the depth of the water being fished. Part of it was likely that the shorter tether transferred takes more quickly to the dry—the longer tippet drops probably absorbed some of the softer grabs so that they didn’t move the dry—but it still held true that my flies were drifting well above the bottom substrate.

Finally, there can be situations where adding weight to your leader can be advantageous. I think of my guides fishing small nymphs on the Lower Sacramento from drift boats, and their occasional need to get these tiny flies down through eight feet of heavy current on days when the fish are sulking. No question, some split shot will increase your hookups in this situation. But in the majority of fishing scenarios, I feel as though I do better with nymphs fitted with tungsten beads, no split shot, and not being overly concerned with the need for them to be scratching bottom. I’ve come to enjoy snagging rocks far less often, as well as the improved casting mechanics with no shot on the leader. Dredging bottom is unquestionably an effective technique, though understanding that it is not always necessary—that fish will routinely move a couple of feet upwards to find a meal—can make for a fun change of pace. casting right on the fish’s head or just behind it, both of which are equally ineffective. As my friend discovered, the key is to take the time to allow the fish to rise several times and “mark” the rise form against something solid in the landscape behind it. You can then cast a few feet above where the fish actually is, allowing the fly to land well upstream of the riser and drift naturally into its line of sight, giving yourself a great chance for success.