“Why did you let him go?” The old timer said to me. “Those are good eating! And they’re invasive. You should never throw ‘em back.”

I was fishing a San Francisco beach and had just released a little 15-or-so-inch striper. The old timer stopped to watch as I landed it, as folks sometimes do. I generally don’t keep fish and don’t really remember how I responded—probably mumbled something about letting them go to let them grow or the fish being too short. But his comment stuck with me and made me wonder. I had a general sense that striped bass were more of an East Coast fish, famously the province of those with thick Yankee accents and Boston Whalers that were actually acquired near Boston. I knew they had come to California some time in the murky past and had made themselves at home. But I had no idea how they had arrived on this side of the continent, let alone how they became such a fixture. So I decided to find out.

Striped bass are among the most popular game fish in Northern and increasingly Southern California, and for good reason. They can be found anywhere from the beaches of Marin County to muddy South Bay sloughs to the winding Sacramento River, depending on the time of year. They aggressively eat bait, lures, and flies, put up a spectacular fight, and can grow to a truly enormous size. Many Californians grew up patrolling beaches and rivers in pursuit of “ol’ linesides,” and continued doing so into their adulthood. But I’ve found that, like me, many of those same Californians weren’t familiar with the complicated history behind the presence of their favorite fish in their home waters, as well as the struggles they face today.

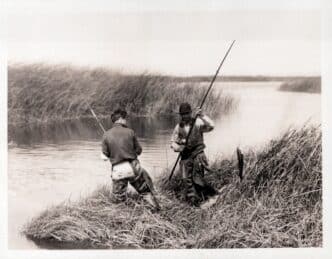

To understand the history of West Coast striper, it’s helpful to get a brief overview of their East Coast ancestors. Striped bass evolved along the Atlantic coast of North America, migrating along a range from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, spending most of their lives in salt water but spawning in the region’s myriad rivers and streams. Long before European settlers arrived, native peoples like the Wampanoag relied on striped bass as a food source, capturing them in wooden weirs as they migrated into tidal creeks and estuaries, then smoking and storing them to eat during the winter and trade with neighboring tribes.

When the pilgrims showed up, they were shocked by the abundance of the striped bass, and given their difficulties farming in an unfamiliar climate, they quickly took advantage. In 1637, Plymouth colonist Thomas Morton wrote, “The Basse is an excellent Fish, both fresh and Salte. They are so large, the head of one will give a good eater a dinner, and for daintiness of diet, they excell the marybones of Beefe. There are such multitudes, that I have scene stopped into the river close adjoining to my house with a seine at one tide, so many as will loade a ship of 100 tonnes…”

Without the striped bass to feed them, the fledgling Plymouth Colony might not have survived. Early colonial historian William Hubbard wrote, “In the year 1623 the Plymouth colonists had but one boat left, and that none of the best, which then was the principal support of their lives, for that year it helped them for to improve a net wherewith they took a multitude of bass, which was their livelihood all that summer.”

The fishery was so vital to the colony that it became the subject of America’s first conservation law—in 1639, the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered that striped bass were not to be used as fertilizer for farm crops, in order to preserve the developing commercial fishery.

In 1670, Plymouth Colony ordained that all annual income to the colony from the Cape Cod striped bass fishery be used to fund a free school—America’s first public school!

It’s clear that the striped bass were a cornerstone of early American culture and diet. As the nation expanded westward, the fishery’s culinary and commercial importance traveled with it.

Fast-forward to San Francisco in 1879, just 10 years after Leland Stanford hammered the final golden spike joining the rails of America’s first transcontinental railroad. At that time, one S.R. Throckmorton was the chairman of the California Fish Commission, an ancestor of today’s California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and the first conservation agency in the country. Mr. Throckmorton had a vision. In a letter to Professor Spencer Fullerton Baird, the first curator of the Smithsonian Museum and the first U.S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, Throckmorton wrote, “I have long had the impression that the great bay of San Francisco, together with the bays of San Pablo and Suisun connecting with it and the number of creeks running into them, affording a variety of qualities and conditions regarding temperature and saline properties, together with feeding material, would be well adapted to the propagation and growth of striped bass.”

Scientific understanding of the natural world was quite different in those days, to put it mildly. Humanity’s total dominion over nature was accepted as a given, the idea of an interconnected ecosystem was just beginning to develop, and the value of fish and wildlife were primarily evaluated through a commercial lens. In that context, Mr. Throckmorton—a Californian transplant himself, by way of New York—saw an opportunity to introduce a highly promising food fish to the young Golden State. So at Mr. Throckmorton’s suggestion, Mr. Livingston Stone of the U.S. Fish Commission collected 162 striped bass from the Navesink River in New Jersey, loaded them onto a train, and shipped them to California. Some of these fish died during their rough transcontinental journey, but about 135 survived. When they arrived, they were released into the Carquinez Strait at Martinez. All of California’s striped bass are descended from these fish, along with an additional plant of 300 fish gathered from New Jersey’s Shrewsbury River and released in Suisun Bay in 1882.

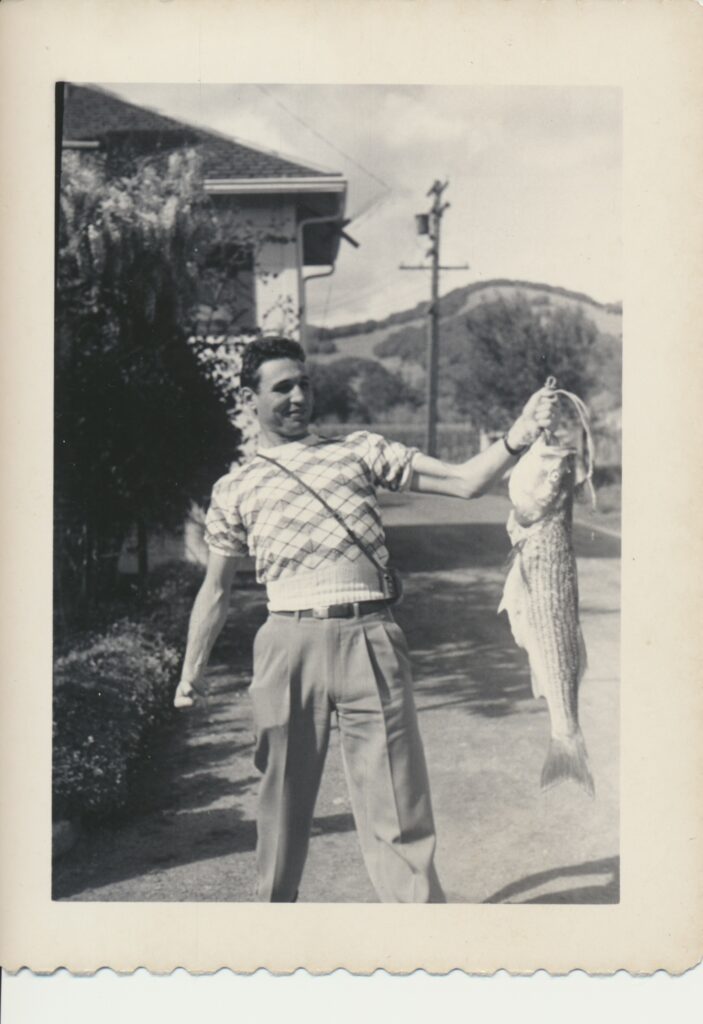

As Throckmorton predicted, the striped bass quickly made themselves at home. Within a few years, they were being caught all the way from Sausalito to Monterey Bay. In less than 10 years, a dedicated commercial fishery had been established, and striped bass were available for purchase in San Francisco fish markets throughout the year. By 1899, the net commercial catch averaged well over a million pounds annually. Commercial fishers plied purse seines and gill nets, scooping up hundreds or even thousands of fish at a time. These fish typically weighed about 8-10 pounds, but CDFW has an authenticated record of a 78-pound fish sold at a San Francisco fish market in 1910.

Eventually, the free-for-all in commercial fishing began to take a toll. Striper had become the favorite among local recreational anglers—bass fishing clubs sprung up around the Bay Area, advocating for increasingly strict conservation laws. As a result, the commercial fishery was permanently shut down by 1935. This period could be considered a golden age for the Bay Area striped bass sport fishery. In 1927, fisheries scientist Eugene Scofield wrote that “on weekends and holidays thousands of admirers of this game fish rig up their rods and set out for the sloughs, bays and ocean beaches adjacent to San Francisco. Not often do they return home disappointed, for the striped bass are ever abundant.”

Unfortunately, the abundance didn’t last, and this is where things begin to get really complicated. California urbanized rapidly after the turn of the century, and folks that are far smarter than me have written extensively about the host of anthropogenic factors that caused the accompanying decline of the Golden State’s fish and wildlife populations. In short, the human population skyrocketed, dams and aqueducts diverted rivers; wetlands were dredged and developed; and water pollution became widespread. And like California’s own native anadromous salmonids, the striped bass suffered. Hundreds of millions of fry were entrained by State Water Project pumps and PG&E power plant intakes each year, spawning habitat in the Delta was systematically destroyed, and populations of forage species dwindled. In the early 1960s, the total striper population in the Bay-Delta system was estimated at around four million fish. By 1980, that number had fallen to one million fish. Far and away the greatest culprit behind this precipitous decline is our intense and ever-increasing diversion of freshwater from its natural courses, which has also devastated our salmon and steelhead populations.

But the decline of the striped bass didn’t attract as much media attention as that of loved native species like salmon, steelhead, and delta smelt. And around this time, public attitudes toward striped bass began to shift. Where ol’ linesides had been valued as a gamefish worth protecting, it was now viewed as a voracious invader, steadily chomping its way through diminishing native fish populations. The CDFW had previously aimed to protect the fishery through the Striped Bass Management Program, established in 1981, which sold striped bass stamps to fund research, population monitoring, enforcement efforts and hatcheries. These efforts were largely abandoned in 1992 amid concerns that striped bass predation was harming winter-run salmon. Large agricultural water users, embattled by the growing consensus that native fish decline was mainly due to water diversion and related habitat loss, decided to blame other factors. In 2008, a group called the Coalition for a Sustainable Delta sued the CDFW, alleging that the Department’s policies favoring striped bass violated the Endangered Species Act by facilitating predation on endangered native fish. The CDFW settled the lawsuit by proposing regulatory changes aimed at reducing the striped bass population, though in 2020, they reversed course again, opting instead for a holistic approach that supports both the recreational striped bass fishery and the conservation of threatened native species.

This brings me back to the old-timer’s well-intentioned comments on that San Francisco beach.

It’s easy to villainize striped bass as an invasive species, much like how humans tend to villainize other perceived “foreign invaders.” But the reality is more complicated.

Prominent fisheries scientists have started calling California’s striped bass a “scapefish” because of the misguided blame it gets for the decline of anadromous salmonids. However, before the massive water diversions that began toward the end of the 20th century, striper lived in relative harmony with steelhead and salmon—all three were able to maintain healthy populations. Salmon smolt make up a tiny part of an average striper’s diet, despite what you might see on social media. Research shows that striped bass mostly eat insects, occupying a similar ecological niche to native pikeminnow. Scientific understanding has advanced a lot since the 19th century, and we now know that it is not a great idea to introduce a foreign species into a complex, delicate ecosystem like the San Francisco Bay estuary. But all things considered the data indicates that striped bass are relatively good house guests, especially compared to other non-native species. As a result, they have become a vital part of California’s aquatic landscape over the past 150-odd years.

Today, stakeholders estimate that about 200,000 striped bass remain in the Bay-Delta system—a far cry from the glory days of the past. They face an increasing number of environmental threats, like most of California’s fish. However, Californian anglers continue to come together to advocate for their striped friends, which supports the livelihoods of guides and outfitters all across the state. Organizations such as the California Striped Bass Association and the California Bass Union work hard to promote sensible regulatory policies, encourage good fishing practices, and combat misinformation. With the help of dedicated individuals like them and the wonderful readers of California Fly Fisher, we can protect and preserve our oddball striper fishery, made up of fish that have settled in so well so far from home.