On the approach of a recent birthday, I began to announce, to those who would listen, that I’ve lived longer than I’m going to live. This seemed to me a remarkable admission, and much as I hated to make it, it forced me to view life from a brand new perspective: From this point forward, I have less time than I’ve had up to now.

Of course, I recognize the absurdity of this new outlook. Given my actual age, there’s a very good chance that I passed the halfway point in my life many years ago. Just because I can behave like a teenager offers little defense against the disturbing evidence revealed to me each glance in a mirror. What the hell happened? you wonder. I feel like I was just getting warmed up.

Not surprisingly, it was John Gierach who pointed out that nobody finds himself on his death bed thinking he spent too much of his life fishing. Granted, there have been spells when I imagined I was spending a wee bit too much time on the water. But it seems safe to bet that such episodes are probably not going to come back and haunt me when I feel my ghost tugging free of this deteriorating body. Instead, I sense, as I gaze both forward and back from my newfound perch at the middle of my life, the only feeling I need fear is the regret that I wasted too much time doing things I didn’t want to do, not that I spent too much of my life doing what I loved.

The gift arrived in a great wooden crate, solidly built, formidable in its dimensions. I needed one of my sons to help me carry it into our house. “What gets shipped anymore packaged like this?” I asked myself. When’s the last time anything showed up in a box built better than most everything inside of packaging today?

It took a screw gun to free the lid. With a #2 square-drive bit. Of course I could have used a pry bar. But my son already had designs on the crate, picturing it as a piece of furniture in his humble student quarters.

The fact is, I had ideas for the crate, as well, seeing as it was built better, and with finer materials, than all but a handful of items throughout my entire house.

Yet by now my attention had turned to the contents of the crate. I had a hunch — no, really, more than a hunch, a pretty good idea, based on clues on the crate itself plus an enigmatic note I had received from a close friend during the winter holidays.

I know only one person in Santa Paula, my old saltwater pal and Baja guide, Gary Bulla. And lately I’d been admiring one of his elegant fly-tying cabinets, very near the size of this crate, situated in front of a bank of floor-to-ceiling windows in the corner of a bedroom I’d been visiting overlooking a river we all love.

These . . . friends,I thought, admiring the panel of solid maple revealed inside the open crate. You mean to tell me she got me one, too? I wondered — while I eagerly had my son help me lift the cabinet out of the box.

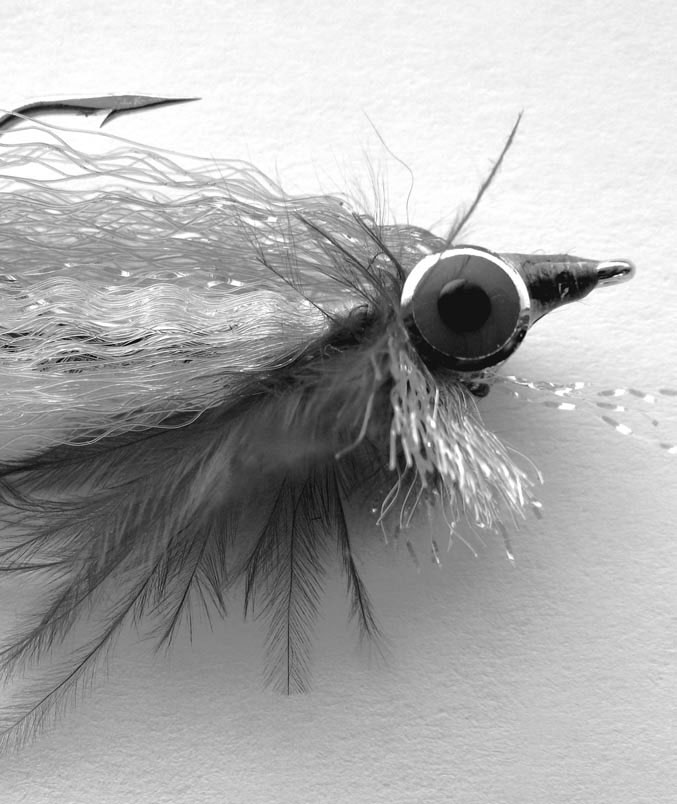

I slid open the top drawer, and there, resting on the green felt, neatly packaged in individual polyethylene sleeves, lay three flies that I’ve come to know well while fishing with Bulla in Baja: the Tuna Tux, Larry’s Minnow, and a Tan Tux with Tails. But what about that other pattern Gary likes so well? What about the . . . Amigo?

I pulled open the other drawers, releasing the fragrance of aromatic cedar used for the bottom of each. No Amigo? But when I slid out the top drawer again, drawing it all the way free of the cabinet, there it was, the fly I associate with a kind of fishing I’ve had in Baja and the California surf and no place else in my life.

Now, the reader may ask: What’s all this got to do with age, flies, or fly fishing? Or even with the themes, as Whitman said, that the Soul loves pondering best: “Night, sleep, death and stars.”

It’s a difficult lie I’m trying to cast to — a tough notion from which I’m trying to inspire a rise.

But let me give it a shot: Say what I might — and I’ve said plenty — about all of the wisdom and wonder available through fly fishing, I’ve reached some strange new territory in my life where I’m about to concede what so many have learned before me. That is, the best reason to indulge one’s passions in this all-consuming, silly game is the people one meets along the way, the friends one makes, the characters one discovers, the stories lived, told, and shared.

The argument might be made, of course, that this particular bit of wisdom, profound though it may be, is available to everyone who lives a conscious life, who pays attention to what is and isn’t important in the brief light of our temporal existence.

Or to phrase this last idea from a different angle, isn’t it fair to ask: Wouldn’t you meet just as many good people and make just as many interesting friends if you spent your life racing sports cars, growing ferns, attending anime conventions, playing bridge, or socializing on … Facebook?

Fair to ask, yes. And a question to which I would answer yes . . . and no.

For it has seemed to me, ever since I sat at a table at Bob Marriott’s fly shop signing books alongside the likes of Dave Whitlock, the late Gary LaFontaine, and our own Seth Norman, that there’s a spirit of goodwill attached to the sport, one that extends so far beyond all expectations of courtesy, generosity, hope, and common decency that I can only assume that the sport is blessed with more than its fair share of noble and angelic personages.

Either that, or else everyone involved in the sport is having so much fun that he or she can’t help but be nice to friend, family, neighbor, stranger, and foe alike.

Or by some grace inherent in the sport itself, good men and good women are attracted to it, because angling has always been, as we know from Sir Henry Wotton, quoted in Walton’s Compleat Angler, “a rest to the mind, a cheerer of spirits, a diversion of sadness, a calmer of unquiet thoughts, a moderator of passions, a procurer of contentedness,” and it begets “habits of peace and patience” in those who have “profest and practic’d it.”

Yet maybe my own generous attitude toward the people inhabiting my fly-fishing life is exactly what happens when you reach a certain age. Maybe this is what’s supposed to happen when you begin to glimpse the end — and from here on out, the whole point seems to be to share the wealth, protect the resources, and have more and more fun.

Or maybe I suddenly think this way because somebody’s injecting something into the avocados I so heartily consume these days.

Or maybe, just maybe — are you ready? — maybe this is what finally happens to you if you fly fish all your life.

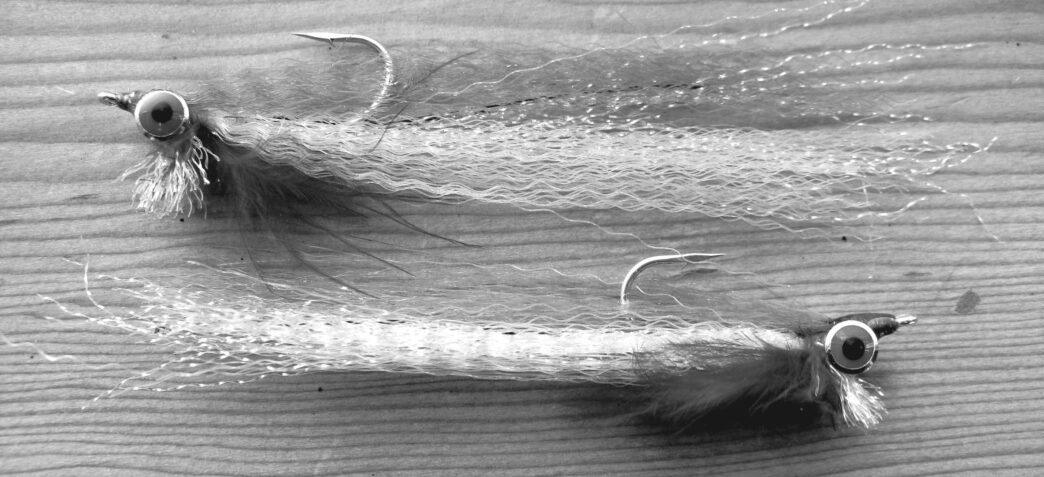

Like so many other flies we tie to the end of our tippets, the Amigo is a derivative pattern, not unique so much as a combination of good ideas assembled into one. It came to me through Bulla, when I returned to Baja following a fifteen-year hiatus spent trying to hold a marriage together and then, afterward, recovering from these hapless efforts. The Amigo looks more or less like a Gremmie mated to a Clouser Minnow. Or mating with a Clouser … or at least suggestive of the two flies getting along a heck of a lot better than a husband and wife on the brink of a collapsed marriage.

Returning to Baja after my long exile, I felt slightly awed by the radical changes in flies and fly-tying materials since my withdrawal years before. I’ve recounted this passage elsewhere in these fly tales. Yet it’s worth noting that when I stopped visiting Baja, Bob Clouser’s Deep Minnow was a brand new pattern, and the first Gremmie had not even been conceived. (No wonder I’m old enough now that I’m sure I’ve lived at least half my life.) One look at the Amigo, however, suggested that good sense and practical insight were still the guiding principles driving fly design along the saltwater reaches of Baja and Southern California, and I could see immediately why Bulla had made it a member of his very short lineup of must-have flies.

But there was something else about the Amigo — certain aspects about it that made it seem familiar to me, that spoke to the demands I knew so well of stalking fish inshore and in the surf. Tying the Amigo to my tippet reminded me of meeting someone who, for some strange reason, already seems like an old friend. I didn’t have to make a single cast, I didn’t have to catch even one fish, to know that I had a fly on my leader that, for all intents and purposes, I wouldn’t need to change all day.

Funny how we know.

Or maybe not so funny — or even strange — at all.

Interested in the history of the Amigo, where it came from and how it came to be, I phoned Bulla. Of course, I also wanted to thank him for the new cabinet, a welcome addition to any living room that offers no degree of separation from the impressive tumult of the fitful, working fly-tying station.

“Don’t thank me,” said Gary. “That friend of yours paid for it. Thank her.”

I said I would do just that.

“And call Guy Wright. He’s the one who can tell you about the Amigo.”

Which is where this fly tale begins to come full circle, how it ends, it seems, practically the same spot it began.

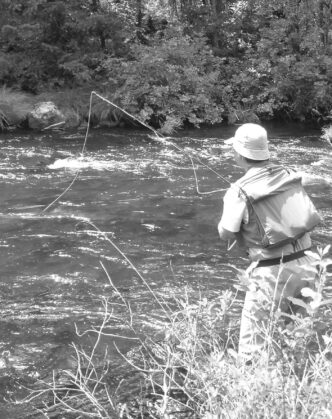

Guy Wright lives in Cleveland now — Cleveland, Ohio. But for most of his life, he did that California thing, growing up with surf on his mind, backpacking in the Sierra, learning a trade that allowed him time for sport while cobbling together a living. Like a lot of the old crew, he kind of figured out the whole fly-fishing in the surf game on his own, walking the Santa Barbara beaches in Tevas with a 9weight rod, a good line, a cheap reel, and a homemade stripping basket. He learned to cast that whole line, all the way down to the braided backing. And he also learned where the fish are and where they aren’t, and that the ones you want most — the halibut, the corbinas, the white sea bass — are feeding predators aiming to make a meal out of your fly.

The Amigo, says Guy, “represents an image, an illusion, of live bait.” Right away I could tell that we speak the same language. He believes the Amigo should be tied sparsely, suggesting something that’s “there, but not there,” thus triggering the predator to strike. Also, by leaving the butt ends of his clipped body materials, he creates both gill plates and side fins, a feature that creates a disturbance in the water as the fly is retrieved. Like all Clouser-style flies, the Amigo swims with the hook point on top, and the dumbbell eyes, set far back on the hook shank, give the fly that “jig” behavior that probably has a much to do with the pattern’s efficacy as all its other attributes combined. The more I talked to Guy Wright, the more impressed I was by the spirit of the angler behind the Amigo than by the fly he created for the Southland surf. The more he said, the more I could tell that I was talking to yet another one of those rarely glimpsed flyrodders stalking the beaches way back when, a guy who certainly would have been a source of insight and information, if not also a friend, had our paths crossed while tracing, when young, the margins of the tides. The Amigo is a simple, elegant fly, an indigenous pattern created by grafting local ideas onto proven rootstock from elsewhere. Yet for me, today, looking down the short slope of life, I see the Amigo as not so much an innovation, but a testimony to the wisdom inspired by a kind of fishing that still seems closer to the heart of the sport than anything money can buy — standing at the edge of the ocean, casting a fly, believing, like fools and heroes, that something wild is about to straighten your line.

The Amigo

by Guy Wright

Hook: Size 1, 4X long

Thread: Red or olive

Eyes: Red dumbbell eyes, 1/24 ounce

Lateral stripe (optional): One peacock herl on each side

Body: Pearl Crystal Hair (midsection) and Super Hair (olive over white)

Fins: Crystal Hair and Super Hair, extended 1/4 inch, tight behind the eyes*

Gill plate: Red marabou

Glue: Krazy Glue or five-minute epoxy

*Note: To create the gill plate and fins, extend the midbody Crystal Hair one-quarter of an inch and tie in tight behind eyes. Do the same with the white Super Hair underbelly. Then tie in the marabou gills. Finish by tying the olive Super Hair on top, in front of the eyes. Glaze lightly with epoxy or Krazy Glue.