Is there a witching hour? Well, if there is on a bass pond, it certainly isn’t midnight. Rather, it is the period of deep dusk. The heat of the day is slowly slipping away. Tiny vestiges of breeze coming off the water tickles the hair on your arms and brings just the slightest hint of cooling air. Sweat no longer drips from under your hatband. The swallows that swooped and soared over the pond have given up their hunt for the night. In the old days, you’d expect to see bats taking their place as the last of the light in the west glows golden. Bats seem to be scarce these days.

The bugs have settled down to a steady hum. You wish for a moment you’d remembered your insect repellent, but instead of putting your rod down on the bank and walking back to the car, you just hope that most of the insects that alight on you are midges, not mosquitoes. The frogs (there seem to be fewer of them each year, as well) have begun to advertise their willingness to mate. For a place that is supposed to offer the silence of the Great Outdoors, it’s awfully darn noisy.

Your only companion is a grumpy old blue heron waiting around to see what the evening produces, the same as you are. He squawks in disgust and flaps noisily away when you come too close. Overhead, the sky still has blue in it, but a darker shade. Night is coming. Out there in the deeper shadows you hear the slosh of something heavy taking a bug off of the surface. There’s also the smacking sound of bluegills doing the same thing. The pond, which an hour ago seemed lifeless in the heat of a summer day, is beginning to come alive.

A summer’s evening is my favorite time to fish for warmwater species. Summer mornings are often too bright, with few clouds in the shiny blue sky, and the fish don’t seem to feed much after the first rays of sun hit the water. The middle of the day is often uncomfortably hot, and even the muskrats and water snakes seem to hide until the sun gets low in the west. Evenings should therefore offer better angling, and this is certainly true for small ponds, where there’s seldom the intense water-skiing and personal-watercraft activity that you find on larger bodies of water.

I think that’s what separates our bigger bass lakes from the ponds. On larger waters, the bass have been subjected to a whole day of roaring boats and splashing lures and baits coming in their direction. Like as not, they’ve deserted the shallows in disgust, and it will take them several hours to recover and venture back near the surface. Bigger lakes with boat traffic are at their best for angling in the morning, when the fish have had all night to lose their caution. If I have to fish a larger lake in the evening (and yes, I do have a couple that I like to fish late in the day), I look for the least-disturbed spots in the back of coves and also for those five-mile-per-hour speed zones that keep fast boats away.

If you’re fishing a pond, you probably got there a couple of hours too early and have already fished much of the available shore. Now that it’s getting dark, you grow increasingly excited with anticipation of what might happen in the next half hour as the sun retreats from the water. This is when bass-bug fishing, the traditional top-water form of warmwater fly fishing, comes into its own. Of course you can catch bass on bugs earlier in the day and earlier in the year, but there’s just something about wading or walking the bank of a cozy bass pond at the end of a summer day that lends itself to the careful application of a bass bug, instead of a big wet fly or a streamer.

On a really quiet evening — you know, almost no wind, no noisy neighbors tossing spinnerbaits, no boat traffic — I like to fish a quality hair bug, because of the way it casts and settles softly on the surface. I am not particularly a fan of having to sit down and tie the things, but I appreciate their gentle drop to the water. The bass seem to enjoy it almost as much as I do. A well-tied hair bug will usually last through several bass, unless, of course, you are a careless caster and heave the thing into stick-ups and razor-sharp tule stems. At that point, you’ll probably get back a bare hook where there used to be a bass bug.

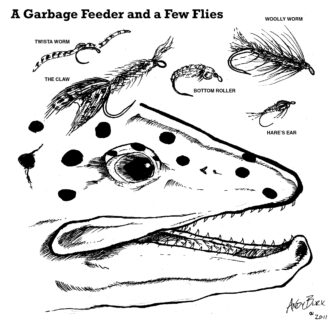

Hard-bodied bugs made of balsa are perhaps somewhat stronger than a hair bug, yet land nearly as quietly. One of my favorite evening bugs for working over lily pads and other floating cover is the Gerbubble Bug. This oddly named balsa bug was created by angler Tom Loving in the 1920s. I’ve read that it is supposed to mimic a small bluegill or crappie lying on its side. In fact, the original is pretty much a Salvador Dali sort of representation of a wounded bluegill, with bright body colors and vivid spots painted on. I’ve recently built more realistic versions of the Gerbubble, and while I like their looks, I am not sure they catch fish any better. Maybe Dali was onto something.

Anyhow, the balsa bug lands gently and pops just well enough to imitate something struggling on the surface. It draws strikes in sunshine and shade and even works fairly well late enough into the dark that you can fish it by starlight. I am convinced that color matters little in the evening, although I personally like yellow or white so I can see the bug until it gets really dark. Then I usually either switch to a black popper, which has a better silhouette against the night sky, or break out the hefty cork bugs that make a fair amount of commotion.

If there is a breeze putting a bit of riffle on the water, I go to the cork popper early and fish it with a bit more aggression. You are trying to get the fish to notice something on a broken and noisy surface, so a bit of extra noise and vibration will do more good than harm. I prefer not to fish open water until it gets really dark, but instead continue to target the kind of cover that bass use all day long when the sun is up. In the late afternoon, the fish will stir around more, and you might get surprised by a large bass working in open, even still sun-lit water, but in most cases, they’ll stick pretty close to cover and shadow.

Besides, there’s nothing more fun than tossing a bass bug into a shadowed pocket near heavy cover that “just has to conceal a big bass” and actually finding a big, aggressive fish lurking there, ready to blast a big hole in the pond as it eats your bug. A really big bass will leave you weak-kneed and shaking. It’s a sort of shock therapy that is highly habit-forming.

This evening fishing is not normally fast paced. I like to wander along the bank, casting the bug to likely looking targets and using as much patience as I can muster to work the bug slowly and carefully in, over, and around bass habitat. Once in a while you’ll find a fish feeding with enough zeal to enable you to cast directly to it — like casting to a rising trout. This gets a little tense. You don’t want to screw up the cast and put the fish down by dropping the bug directly on its head, and you don’t want to spend too much time casting around the fish’s location, because that may do the same thing.

Every so often you get it just right, and the bug disappears in a savage swirl the moment it hits the water. You fight the fish to a standstill, lift it up for inspection, and slide it back into the water. You’d really like to brag to somebody, but if you’re lucky, you are alone on the pond, and there’s nobody to appreciate your prowess. On the other hand, by the time you get around to the next club meeting, your bass, which was a dandy three-pounder when you caught it, is now tipping the scales at more than five pounds — and putting on weight as you speak. . . .

Mostly your evening will consist of catching a few fish. Most will be bass, but a percentage will be larger bluegills or even a crappie or two, in the right places. I’ve even caught very respectable redear sunfish on a small popper a couple of times, even though most anglers will tell you redears don’t feed on the surface. Perhaps the redears haven’t read that particular rule.

The bass won’t be all that large, either. Oh, sure, some will be respectable fish in the two-to-three-pound range, but really big bass — nearly always females, if they are much over five or six pounds — are uncommon. Still, the thought that you are fishing where monsters perhaps swim is enough to keep your attention focused.

The real fun is getting to practice the craft of throwing wind-resistant bass bugs to real targets that could be monster bass. It’s an art form that transforms an otherwise sultry summer evening into an adventure, requiring you to adjust the way you fish by using a casting stroke that is slower and more deliberate than typical with a fast-tip graphite rod and small trout flies.

Bass bugs will turn fly casting into work, if you let them. But if you slow down your stroke and fish a rod that is a little forgiving of timing, the gentler sweep of the cast becomes a source of delight. The big bug sails past you and on out into the dark, headed for what? That’s the fun of the whole thing. It’s laid-back, slower fishing, but with the same anticipation of the strike you get on any trout stream.

I sometimes cast bass bugs with graphite rods and have several that will do a credible job of it, but fiberglass (or bamboo, for the purists and those with more money to spend) is the material of choice for the larger bass bugs. There’s just something graceful in the timing you get from casting wind-resistant bugs on a glass rod.

Waiting for your back cast to straighten out in the gloom slows the whole process down to a methodical pace I find relaxing. There’s less of the “hurry up and get the fly on the water” thing going on with bass bugs. The whole world seems to be suspended, waiting for night to fall. On the other side of the pond, one of those automatic yard lights comes on at a farm, something that you’ve never liked. They clutter up the night and smother the stars with poorly directed light. Finally it gets truly dark. You can no longer see the bug and are fishing mostly by luck and a feeling for a place you’ve fished so many times before. The stars are well and truly out now, sprinkled like sand along the arc of the Milky Way, and the first hint of real coolness comes whispering across your neck. The fishing has slowed, and it is time to reel up and put the rod away for another evening. You stand in the dark at the side of the car, listening to the night. You’ll be back.