I live among canyons — lots of steep and deep canyons: east-west canyons, north-south canyons, and those that, notwithstanding our need for tidy categories, defy such labels. I’ve spent a considerable portion of my life finding and exploring (and sometimes making) trails that descend into canyons. I have the great fortune to count among my friends others who share this passion — perhaps for reasons nonpiscatorial, but to us, that is a distinction without a difference. It’s really about the adventure, the history, the beauty of places without windows, cellular service, or urban hubbub, the wildflowers, the trees, the cliffs, and yes . . . the mosquitoes. The fact that there are, at least where I live, fish living in the creeks and streams that meander — or in some seasons, roar — timelessly along the foundations of our canyons is frosting on a very delectable cake. But then, I’m a frostingaholic. I don’t have a psychoanalyst, but if I had one, I suspect I would be told that I’m driven — maybe even compulsive, determined. It’s this bad: when I hear of a trail that is — or may be — here or there, I’m all over it like a cheap suit. After doing my research, if I discover that it leads to fish habitat, I, my GPS, and any of my canyon-angler friends willing to try will find it. And the finding, however long it takes, is sweet.

Then, lest I get too impressed with myself, there’s Richard, whom I met one evening at the bottom of a canyon in the Middle Fork of the American drainage. I had seen a vintage van parked at the trailhead pullout. The immediate nemesis sensation — “Darn, there’s someone on my water” — hit me somewhere down the trail as the noise of thrashing pocket water reached my ears. Later, near that time when “out of here” is fraught with meaning, I noticed a backlit, wraithlike figure coming toward me — slowly, obviously in pain, gait almost unrecognizable: moving the left leg forward with the aid of a long stick, then bending over and picking up the right leg with the right hand, bringing it forward, then following along with the left leg — again and again.

“Are you hurt?” No answer. Closer now. “Bad knee.”

“How did you get down here?” “Slowly.”

“How will you get out?” “Slower yet.”

I watched in disbelief as he crabbed past me toward the trail back out. Turning around, he stared at me, smiled, and said something like, “Don’t stay down here too long, sonny; dark’s a-comin’.”

Sonny? Oh, well, one more fish. I overtook him about halfway up, where he again scoffed at my offers of help. “See ya at the top.” And I did. We talked as we swatted mosquitoes, me learning that this was his tenth (or some nth) day in a row hiking the trails into this canyon.

“Where’s Skunk Creek? I can’t find it down there.”

“Two miles farther downstream.”

Thanking me, he climbed into his van/home and slammed the door.

Driving out, I parsed through this lesson in humility, wondering if “sonny,” who is actually three years older than Richard, would have the guts to keep bending over and lifting his right knee for the next step.

The Uniqueness of Canyon Fishing

What is it that sets canyon creeks and rivers apart from those found in areas of lower elevation or “drive-up-and-fish” venues? First of all, they are normally high above impoundments or other obstructions. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they are always pristine. Indeed, at least in my neighborhood, the scars left by ravaging Forty-Niners during the Gold Rush days adorn the landscape of the canyons, along with the hulks of their rusting equipment — much of it located right next to the water.

Second, canyons are often remote and can require a strenuous hike to reach the water. If that’s unwelcome news, then the good news is that the need for the hike acts as a de facto limit on angling pressure.

Third, the fish are generally hungry and . . . well, dumb. But this is not always true. They can be impossibly, frustratingly shy, especially during times of low water, requiring considerable stealth and angler savvy. Their hunger stems from the limited available aquatic food base, a fact that further distinguishes canyon streams from others. For example, the geomorphology of the creeks and streams in the upper North and Middle Fork of the American drainages features many stretches of bedrock and precious little bug-producing substrate. (In recent proceedings concerning the Middle Fork before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the science team characterized the drainage as “infertile” in terms of aquatic insect life.) This is not entirely bad for anglers, because the fish will take terrestrial imitations readily. (Ants should come to mind.) Finally, canyon-dwelling fish are generally wild and genetically free of influence from planted trout, especially where natural fish-passage obstacles such as waterfalls are found.

The Elements of Canyon Fishing

Some of what follows is applicable to trout fishing in general, irrespective of stream size or location. But canyon fishing poses stark differences and contrasts that get directly to what I personally consider to be the essence of fly fishing: on-stream problem solving in an ever-changing, challenging environment. I’ve guided anglers in canyons for many years, and have observed mistakes born of assumptions that appear to be based on the angler’s experience fishing large (or small) tailwaters or “flatland” streams. For example, the use of floating indicators as a method of nymph fishing is not always the best tactic in small canyon streams, but in many cases, it is the canyon novice’s first choice. Problem solving in a canyon stream setting requires a working knowledge of the peculiarities of canyon venues. To fish canyon water successfully, you need to hone your skills for reading water and employ the proper approaches and choice of tactics and strategies.

Reading Water

While this is not intended to be a primer on reading water, it pays to know that canyon trout have many predators, most of them of the winged variety. The instruction “Hide or die” is part of a canyon trout’s genetic makeup. Like other trout, they lose some of their inhibitions during a hatch, but even then, in my experience, their rise forms and feeding cadences differ from those of lower-elevation trout, whose predators may not be as numerous. Rarely have I seen slow, rhythmic feeding patterns in the canyons. Rather, rises are quick and sporadic, as the fish dart upward from concealment and back down to safety. As canyon anglers, we need to understand the where and when of a canyon trout’s safe refuges. Here are some of the factors that should be taken into account in reading canyon water.

The time of day will affect trout habitat. Water that holds fish in the early morning can be barren during the time the sun is directly on the stream. This problem is compounded by the small size of pools and pockets in canyon streams.

Weather has a big effect, too. For example, on cloudy days, the water retains its opaque, mirrored surface, providing concealment and safety for trout. Still, canyon trout tend to be instinctively reticent and may not be as quick as other trout in returning to “normal” feeding lies.

Edges and seams are key holding spots when they feature broken surfaces that keep predators from seeing fish. Look for fish on the soft sides of seams, because they can live there with less energy expenditure. Canyon trout favor transitions — from a light to a dark bottom, from shallow to deep, from sun to shadow. In other words, these trout favor dark areas, deeper spots, and shadowy places. Of these, I have found that canyon trout prefer dark stream-bottom areas over other types of cover.

Sun angle is also important. Lower angles will tend to highlight floating insects for prowling trout. The downside is that you — the angler — will also sport a scary profile when backlit. This problem is magnified on a tight canyon stream where trout readily notice background movement. Seasonal variations do occur. For example, during the late summer and early fall, when temperature and oxygenation strongly influence where fish will hold, look for canyon trout in frothy, highly oxygenated water. Often they will be located directly beneath a foamy head at the top of a pocket. In the spring, the water will generally be well-oxygenated, so those spots may not be go-to areas.

Canyon streams often feature what I call “interior pockets” within larger pockets. These are subtle changes in depth and/or current speed that can easily be overlooked. A good example would be a plunge pool where the water enters the center of the pocket and there are obvious clear, slower currents on each side of the fast tongue. Certainly, those areas are prime targets, but a close examination of the faster tongue will at times reveal an interior area where there is a slowdown that may be the lair of a larger trout. While such situations do exist in larger or lower altitude streams, they are much more common in canyon streams that feature almost entirely pocket water.

There are other factors that affect the behavior of canyon trout, but an understanding of those discussed above will increase catch rates. It also pays to know the components of a piece of pocket water or pool when trying to determine where the fly should be placed. Again, keep it simple. The head of a pocket or pool will normally have a frothy center with lines of clearer water beside the frothy tongue. These clear spots at the top of the pocket are prime fly-placement zones. In canyon streams, the largest fish may well be found in a tiny, one-square-foot clear area within a pocket.

Downstream of a the pool’s head the flow will usually slow, yet retain a broken surface. Trout will often follow flies out of the foam and into this area before taking them. Drop flies into or onto the upper part of the pool, and if they aren’t taken there, they may be taken in the center.

The tailout and lower lip of a pool can be productive as well, particularly in lowlight situations, when fish are likelier to leave sheltered places and feed.

Strategies, Tactics, and Techniques

The terms “strategies,” “tactics,” and “techniques” have somewhat differing meanings, but for our purposes, let’s bundle them into the concept of the “how-to” of canyon angling. Most of what follows is common sense, and some of it involves general trout-fishing principles. Still, as pointed out above, it would be a mistake to view canyon fishing as a mere microcosm of its larger-stream counterpart. Over my many years prowling around in canyons looking for trout, I have developed a list of ten how-to fundamentals for success in canyon trout fishing. Here they are.

Approach from below. Whenever possible, I wade and fish upstream. Except in the reverse flow found in eddies, trout generally face upstream, so this principle is primarily a concealment technique essential to small, confined areas. Occasionally you may come across impassible areas, such as closed-in canyon walls forming a deep pool. Your choices are to climb around the obstacle, swim through it, or turn around and head out if passage is otherwise too dangerous.

Use short-line nymphing techniques in pocket water. Almost all of the water in canyon bottoms will be pocket water, but there will be intervals of quieter water. When I encounter one of these, my preference is to keep my short-line system set up on the rod. If dry flies are called for, though, I simply remove my nymphing tippet section and replace it with the appropriate size and length of tippet suitable for dry-fly fishing. The switch (both ways) takes less than five minutes. I do not carry two rods, especially where I know or suspect that some climbing or bushwhacking will be involved.

For a primer on short-line nymphing, see my article on that subject in the May/June 2011 issue of California Fly Fisher. I do not use a floating indicator, but rather an in-line indicator, which easily allows for changes in depth. My nymph choices are simple. I set up initially with what I call my “three deadly sins”: a size 14 rubber-legged beadhead Dark Lord on the upper dropper, a cased-caddis imitation as the bottom or point fly, and a soft-hackle fly as a “stinger” hung off the bend of the point fly with about 14 inches of 5X or 6X tippet.

Combine short-line nymphing techniques with swinging. Pocket water normally features repeated small pools, most too short to swing a fly through after a short-line drift. But occasionally there will be a pocket that has a long tailout. A deadly approach for this situation is to shortline the upper portion of the pocket and then allow the rig to swing through the tailout once it passes your position. This is where the soft-hackle fly will shine as a fish catcher.

Use a swinging technique in deep pools. This does not require changing flies unless you otherwise desire to do so. Simply add more weight to the rig, cast it upstream and across (lob it, really), mend, allow the rig to sink deep, and swing it, just as you would a streamer. Sometimes, especially if I’ve spotted a large fish in the pool, I take the extra time to insert a looped piece of T-8 tungsten line between my fly line and the leader setup, in order to get the rig to sink faster.

Use a “reverse swinging” tactic in pools with large eddies. There are times, especially during somewhat higher spring flows, when large eddies form in pools. An interesting approach for this situation is to cast a short line into the downstream flowing part of the eddy and allow the flies to reverse direction without any line manipulation, unless a mend is clearly called for, which is almost never. I call this technique “reverse swinging.” You will have to watch your in-line indicator or the visible upper part of your fly line closely for any telltale movement signifying a take. In this situation, I’ve often hooked large fish, but the takes can sometimes be subtle and difficult to detect. When in doubt, strike. I don’t change flies for this type of pool.

Try the “laissez-faire” technique in pools featuring a large, midstream tongue of fast water. Visualize a reasonably wide pool that has a fast tongue of water entering at its head and extending throughout the pocket. Often there will be a slower section between the angler and what geomorphologists call the “thalweg” — the deepest continuous part of the canyon, its center high-flow area. This can be difficult to short-line nymph because the slower section will normally be narrow. Here I simply cast the rig into the seam and let the flies find their own course downstream. Strikes are hard to detect, because there will naturally be slack in the leader. But since the flies are moving along the seam at a rapid pace, trout need to be quick to snatch them out of the current, resulting in a quick jerk of the in-line indicator. If the strike is visible, a hookup is not always certain because of the slack. Occasionally, however, this technique will work. It’s better at least to give this water a couple of laissez-faire casts than pass it up. This situation can also provide an opportunity to fish the other side of the thalweg with normal short-line presentations. This will require a long reach over the tongue of fast water, and wading into the soft water on the close side can be tricky.

Short-cast dry-fly fishing. Some anglers tell me that they prefer to fish with nothing but dries in canyons, using attractor patterns, terrestrials, or hatch-matching flies such as a Parachute Adams, Pale Morning Dun adult, or caddis imitation. The main mistake I’ve observed when people do this is that they cast too far. Canyon pocket water always features currents that twist through the pool. These currents will cause drag — and at times, even microdrag will ruin your drift. It is best to make the shortest possible cast, using the softest water available in front of you for line management. Still, my preference is to use nymphs, unless that is unproductive or fish are obviously feeding mostly on surface bugs — aquatic or terrestrial. When I can’t coax fish to my nymphs, I normally begin fishing dries with an ant pattern such as Cutter’s Perfect Ant or a winged version, then go to my own attractors, including a fly I call the Lime Green Caddis, which is nothing more than a fly with a wing of medium-colored natural deer hair and a palmered hackle trimmed off at the shank bottom, also sporting a short deer hair tail and a lime green dubbed body.

Dapping a dry fly. Canyon streams call for different line-management techniques due to the multiplicity of internal currents within the typically short pools, and this technique is a variant of the previous one. But here, there is no line or leader on the water. Rather, the angler carefully casts the fly to key trout lies and lifts everything but the fly off the water. This prevents currents from grabbing the line and leader and also deals with microdrag. Consider this: The rod is 7 to 9 feet long, your arm is close to 3 feet long, and you can lean out another foot or two. You can also hold 3 or 4 feet of line and a 9-foot leader off the water by raising the rod tip high. You can cover a lot of water just by employing this highly productive technique, and the small size of canyon stream pockets makes it easy to use.

The dry-dropper method can be effective if used properly. I rarely resort to this tactic, but it can be called for where there is a long tailout at the end of a pocket. As mentioned above, I normally use the short-line-plus-swing tactic here. However, if that doesn’t work, I tie on a large dry fly such as Bill’s Big Fish Fly (see the September/October 2009 issue of California Fly Fisher) or a grasshopper imitation (if it is windy and warm) and drop a couple of flies off the bend of the dry. One of those flies will be a soft hackle (usually at the bottom), and the other will be one of my own creations, such as the Peatridge Hotwire Nymph (see the November/December 2009 issue of California Fly Fisher). Casting this rig can be limited by overhanging and streamside vegetation or high rocky banks. Consequently, it pays to learn how to roll cast efficiently and accurately. At times, the dry-dropper technique needs to be combined with the dapping approach mentioned above.

The downstream “twitch” drift can save the day. There are days when nothing seems to coax trout to the fly. When this happens, it may be time to tie on a small nymph or dry fly and lengthen the leader to 12 feet with an extra couple of feet of 6X or even 7X tippet. Such a setup is not exactly a dream to cast, but this technique does not call for long casts. The key is to get the fly, leader, and maybe a little line on the water at the top of the pool where you are standing and then twitch the rod tip to send the slack from behind your rod hand downstream at the same rate as the current, thereby preventing drag. Remember to twitch out only slack, in order to keep the fly from jerking around with the twitch. This works only where there is enough of a tailout for the fly to cover. If it’s just a short pool that dumps into another pool, this tactic most likely won’t work. I use a small nymph first, with no weight on the leader, so that the fly meanders seductively downstream with the current. If that doesn’t work, I try a small dry fly. In either case, if there is any drag perceptible to the fish, even microdrag, they will ignore your fly, except for the occasional suicidal victim.

For good measure, here is an eleventh tip. We all seem to hate it when our dry fly sinks, and we automatically start to retrieve it, with the fly skating or dragging as we do. Instead, deliberately sink the fly, let it swing to the end of the drift, and allow it to hang down below you for a few seconds. You might get a surprise slashing take on the swing from hungry canyon trout or even a grab on the retrieve.

It is best not to attempt a solo venture into deep canyons. A companion can save your life if an accident happens. I have previously pointed out the risks that will be encountered along canyon trails and bottoms — see the July/August 2011 issue of California Fly Fisher. Still, on balance, for those in adequate physical shape, the canyon experience is clearly worth the effort. Once you’ve tried and enjoyed it, it will get into your blood and attach itself to your psyche like one of those darned ticks that we all love to hate.

Gearing Up for a Canyon

For day trips, keep things simple and minimal. Think through each item you plan to take and ask yourself: Do I really need this? Much of the time the answer will be “No.” Develop a checklist and stick to it. Here is mine, developed over many years and miles of canyon hiking.

- A multipiece rod (the more pieces, the better), 7 to 9 feet in length, for a 3weight or 4-weight line. Most often I carry my seven-piece 8-foot 4-weight.

- An inexpensive, light, but sturdy reel. Canyon environs are not healthy places for expensive, fragile reels. A drag system is unnecessary. The fish are mostly small.

- A floating line. My preference is a weight-forward line because of its broad range of uses.

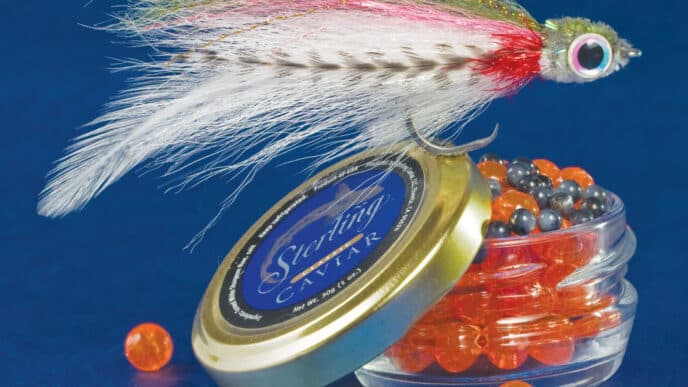

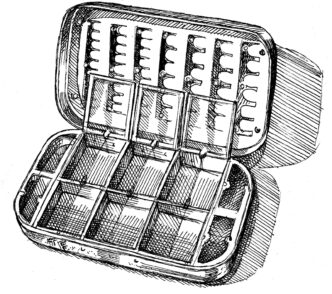

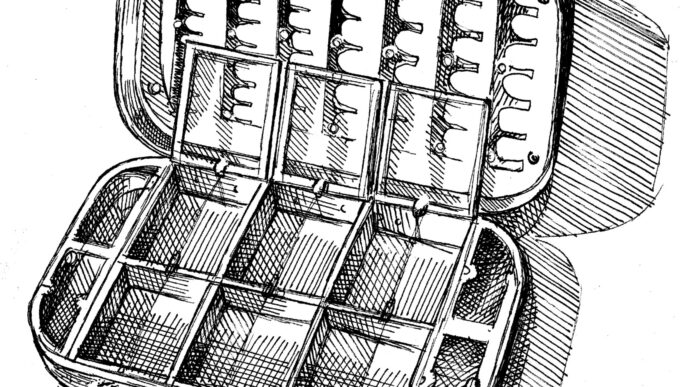

- A single lightweight fly box with a selection of nymphs, wets (including soft hackles), dries, terrestrials, and streamers. Bring only enough flies for the day, unless you are on a multiday trip. It’s a good idea to include a large dry fly such as a hopper pattern to use when “hopper-dropper” situations arise. I don’t bring bobbers of any kind, preferring to use short-line nymphing tactics.

- Lead-substitute split shot in various sizes. I put them all together in a film canister.

- Floatant — both gel and powder.

- A 7-1/2-foot leader tapered to 4X for dry-fly fishing. To this I add 5X or 6X tippet material as needed to lengthen or reduce diameter. I also carry a short-line leader setup for a quick changeover to nymphing.

- Monofilament tippet spools of 3X, 4X, 5X, and 6X material. Expensive fluorocarbon is neither necessary or desirable.

- Looped 3-foot, 5-foot, and 7-foot sections of T-8 tungsten line to convert my floating line to a sink-tip line, in case I need to sink a streamer into a deep hole.

- Nippers and forceps. I use a length of old fly line to hold them around my neck.

- A small plastic box with ibuprofen tablets, salt tablets, antibiotic ointment, and a few Band-Aids.

- Bug repellent (I use the tiny spray bottles) and a small tube of sunscreen.

- A water-filter bottle (much lighter than filled plastic bottles).

- A small fanny pack for the fishing essentials. It fits easily into my day pack.

- High-energy foods in sufficient quantity to last the entire day, including energy bars, almonds mixed with raisins or craisins, and similar concoctions.

- Lightweight wading boots (I prefer the spiked, sticky-rubber bottoms) and neoprene socks. Except where the hike is long and steep, I wear my wading boots as hiking boots, with the neoprene socks over hiking socks. If the situation dictates it, I tie the boots to my day pack and wear my hiking boots. An extra set of hiking socks is often useful.

- A lightweight hiking/wading staff with a stout rubber tip. (An uncovered carbide steel tip makes too much noise in the water.) I prefer the adjustable hiking variety (they are strong and light) and attach a simple lanyard to it for wading.

- If I am going into an unfamiliar area, I include up-to-date topographical maps, a compass, and a GPS unit.

- If desired, a small digital camera and a small LED flashlight.

This sounds like a lot of stuff, but it is all very light and compact and easily fits into a good day pack.

Bill Carnazzo