The first time I went kayak fishing in the ocean, I found myself thinking, Boy, this is pretty easy. You could do all kinds of clever things to send your fly down to where the fish were but it wasn’t long before I recognized that I got most of my strikes while paddling around with my line dangling in the distance behind me. Tom McGuane once described trailing a Mickey Finn behind a canoe as “about the minimum, fly-wise,” yet the first time you hook into a tuna or other pelagic speedster and feel yourself getting dragged toward the middle of the sea, you can be forgiven for rehearsing lines to describe this epic battle while ignoring altogether the lowly means by which it began.

Of course, I also soon noticed that the experienced kayak fishers were hooking a lot more fish than I was — and usually bigger and better fish, too.

Fishing a mangrove estero in Magdalena Bay confirmed my suspicions that there’s a lot more to kayak fishing than the beginner first sees. Attempting long, accurate casts while seated at water level will remind you once again of the ugly little secrets you try so hard to ignore in your loop and casting stroke. Add wind, strong tides, and the very necessary paddling licks to position yourself at an angle from which you can actually launch a cast, and suddenly you realize you not only need to be an accomplished fly fisher to succeed at this, but you could also use the cool head of a harbor pilot and the facility of a bow hunter just to get yourself in the game.

And I haven’t even mentioned how to deal with that damn paddle.

So when my old pal Fred Trujillo said he was driving to Reno to pick up a Hobie fishing kayak that he found on eBay, and then when he started catching fish with a simple squid pattern he concocted that “even the salmon are going nuts over,” I figured it was time to send him an invitation and sit him down at The Roost to see just what it is that’s captured his imagination these days.

At the very least, we need to give Fred’s squid a name.

My own attempts — at creating squid patterns, not naming them — have been marginal, at best. Yet ever since tying my very first Seaducer — a fly with as much story under its hackles as the Matuka streamer or Green Butt Skunk — I’ve kept an eye out for patterns that suggest creatures that swim in the surf and sea besides baitfish. No doubt squid get our attention when they’re left behind by the tide, looking like so many skinned Chihuahuas lying dead upon a beach — and if you worked hard enough at it, and employed enough rubber in the fly, you could end up with something resembling a hoochie, a trolling lure known up and down the coast in all manner of conventional-angling circles.

By way of context, I should also mention that squid claimed a spot in my personal angling history when, as a bait fisher, I used a chunk of it, freshly thawed, to hook the biggest sheepshead I’ve ever seen, anywhere — a beast I eventually lost at my feet while standing on a wave-swept rock, wondering if it’s okay to eat these things.

It is.

And this: A long, long time ago — even before I lost that big sheepshead — the sea wall in front of the raggedy beach break known as Lots between La Jolla Shores and Scripps Pier featured, for a spell, what seemed to me the slyest bit of graffiti — Squid me — which probably offers as much explanation as any for why I became a writer.

I’m a little nervous when Fred arrives. A professional tyer, he makes it a habit of setting out the exact materials he needs, and nothing more. Where my tying station, whether at The Roost or on a picnic table on the Deschutes, will soon look like a dog tore into my supplies of feathers and fur, Fred will still be working with the same bits and pieces he began with, turning out nearly identical examples of the pattern he’s tying.

That lesson right there is worth the price of a magazine.

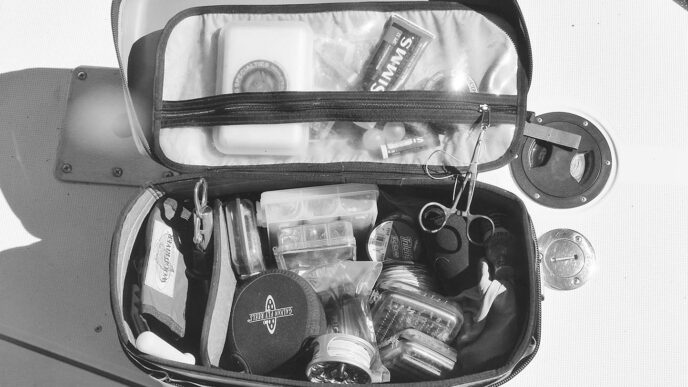

But today, Fred shows up with a toolbox full of materials. Don’t tell me it’s going to be one of those patterns. Like many tyers, I’m a minimalist — that is, I want to do the minimal amount and still end up with a fly that works. Guides are experts at this kind of tying. I’ll tie a replica sea anemone — with moving parts — if I believe I need it to catch a fish. But I’d much rather tie an all-white baitfish streamer and go fishing, working on craft and presentation to get the job done.

While Fred piles up a menu’s worth of plastic packets and other paraphernalia, he recounts some recent kayak-fishing news. He’s told me — hasn’t he? — about getting spilled in that run we sometimes wade across to get to a couple of favorite steelhead holes. And over on the coast, a guy after rockfish got caught inside by a set wave and lost everything but his life. Of course I’d heard, hadn’t I, the story about the guy in Hawaii who just had his leg bit off by a great white and bled to death before his rescuers could get him to a hospital?

So when am I going to get a kayak?

Turns out Fred’s brought not only a well-stocked stash of materials to go with his motivational kayak tales, but also his full arsenal of squid flies. So enamored of late with their effectiveness while fishing for anything that swims in the sea, he’s been creating an assortment of variations, all of which point back to Mark Mandell’s original Calamarko Squid, a pattern that first showed up in Les Johnson’s Tube Flies from 1995. Fred likes tube flies as much as anybody, but he’s started tying his squid pattern with a trailing “stinger” hook, a practice employed by steelheaders who feel it increases their touch-to-hookup rate. I’ve seen a few online photos of the Calamarko Squid, and although Fred seems to have wandered some ways away from the original pattern, you can see again that here at The Roost, as elsewhere, we’re nearly always dealing with derivatives, flies that belong to a lineage that stretches far beyond our own sudden individual genius.

Still, Fred knows a few things — and it’s a pleasure to watch him work. Despite his shaved head and wrestler’s build, he’s got the fine wrists and delicate touch of a jeweler, and he ties with an economy of effort that’s similar to what you notice in a sound and practiced caster. An extra thread wrap is as senseless as an extra back cast. Enough is enough. One more is too many. Start there and you begin to notice a dozen different ways you waste time picking up tools and setting them down, fussing with materials that could have been prepared before you began tying, fiddlings and false starts that not only break your tying rhythm, but leave you frustrated because of the extra effort required to wrangle a fly into shape.

Practice makes perfect, but like most everything in this kooky sport, if you don’t practice smart, all you do is end up developing bad habits.

I ought to know.

Parasquid? Squidillo? Calamarillo? Try as we might, we’re unable to come with a name that rings true. Squid Vicious, I’m sad to report, has already been claimed. Because squid patterns seem perfectly married to kayak fishing, I suggest we switch part of the fly to yak hair; that way we can use a play on words and call it — Fred stops me with a look that says that’s the dumbest way to go about designing a fly he’s ever heard.

A fly, of course, is more than a name. And as I paw through Fred’s lineup of squid patterns, I suspect that what he’s tied this evening at The Roost is merely another stage in an evolution that still hasn’t reached completion. When the pattern stops evolving, a name will come. Or vice versa.

Until then, Squid me.

Materials

Hook: Mustad 3407, size 2

Thread: White Danville 3/0 monocord; at Step 5, switch to fine Danville monofilament

Stinger loop: 20-pound to 25-pound fluorocarbon

Stinger hook: Matzuo octopus hook, size 1

Tail: White saddle hackle

Topping one: White Slinky Fiber or FisHair

Topping two: Fluorescent shrimp pink Iceabou

Sides: Fluorescent shrimp pink Krystal Flash

Body: Medium Ever Glow tubing

Eyes: 3/16-inch stick-on, black on red

Tying Instructions

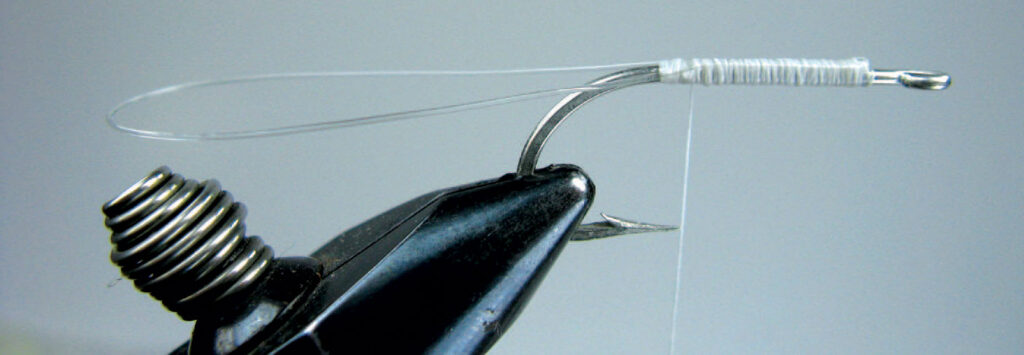

Step 1: Secure the hook in the vise and start the thread. Create a stinger loop approximately the same length as the hook. For security, leave the front ends of the fluorocarbon loop long, then fold them back along the hook shank and cover them too with thread. To secure the stinger hook, run the loop through the eye of the hook, slide the loop over the point of the hook, and pull tight. If you feed the loop through the top of the hook eye first, you can get the hook to ride upside down behind the fly.

Step 2: Select three or four saddle hackles from each side of a neck. Clean off the stems so that you’re left with feathers that extend an inch or so past the back of the stinger loop. Secure the feathers along both sides of the hook as though you were tying a Lefty’s Deceiver.

Step 3: Lay a couple dozen fibers of Slinky Fiber or similar material along the top of the saddle-hackle tails and about even with the tips. Secure the Slinky Fiber along the length of the top of the hook. Then fold the fibers back and, keeping them aligned with the others, wrap the thread back to where you started. Clip the ends of the folded fibers to match the length of the others.

Step 4: Follow the same procedure with the fluorescent pink Iceabou.

Step 5: For the sides of the fly, start by aligning Krystal Flash along the side of the fly nearest you. Again, wrap the thread forward, fold the fibers, and now align them with the far side of the fly. Wrap the thread back to the bend of the hook, then advance it to just behind the hook eye. Whip finish, cut, and start the monofilament thread.

Step 6: Wind the monofilament thread back to the original tie-in point. Cut a length of Ever Glow tubing about the length of the hook plus the stinger loop. Pull the packing material from inside the tubing. Using a bodkin or similar tool, unravel the back two-thirds of the tubing. Slide the tubing over the eye of the hook, so that the unraveled portions extend wildly around the other materials that extend past the bend of the hook. Wrap the monofilament over the intact tubing, then run your wraps forward and back over the length of the hook shank, creating an even body.

Step 7: Stick eyes on at the back end of the body. Because you are tying with monofilament, you can wrap the thread directly over the eyes. Continue to use the thread to create an even, cylindrical body.

Step 8: Whip finish at the eye of the hook. Cut the thread and cover the entire body with your favorite epoxy or other transparent material.