Even in the specialized niche of saltwater fly fishing, the sport is rife with a diversity of opinions regarding preferences for species, locales, tackle choices, and presentation strategies. However, the one issue that would garner nearly universal consensus is the visibility of one’s target. I’ve never met anyone who would disagree that sight fishing is the pinnacle experience of our sport. Whether it’s a bluegill approaching a tiny popper or the sword of a billfish suddenly slashing a teaser, or better yet your fly, the visual element magnifies the experience many times over. As I mentioned in my recent piece on mako fishing (“SoCal Sharks on the Fly,” California Fly Fisher, May/June 2014), the fact that you can see the shark homing in on the fly maximizes the excitement level not only for the angler, but for everyone who witnesses the event.

Much as I prefer this mode of fishing, the reality is that for the vast majority of saltwater fly fishing on California’s coast, the opportunity to sight fish seldom presents itself. Most of the time, we’re preoccupied with blind casting. The term is a bit misleading, because when “blind” casting is executed properly, you are not actually casting haphazardly. Ideally, you don’t simply present a fly in just any part of the water that is within casting distance. The object is to work areas that you believe are holding fish, located by reading the water. We look for signs such as bait, birds, structure, bottom confirmation, water temperature, and tides to help alert us to the fact that fish may be frequenting the area. However, despite the importance of these visible signs, this does not fall within the province of what normally is considered sight fishing. Nor do instances when I’ve been privileged to see breezing yellowtail and dorados track and smash my streamer patterns at offshore kelp paddies or the flash of a yellow fin rocketing to the surface to attack a popper. They are adrenalin-filled experiences, largely due to the visual element, but these, too, do not really qualify as sight-fishing excursions. Furthermore, the downside to all this is that these encounters are not readily accessible and can require a considerable outlay of dollars.

Welcome to the local surf. If you have been reading this magazine for any length of time, you are well acquainted with the fact that for a high percentage of the West Coast’s population, the surf is easily accessed, and fly fishing the surf zone is one of the most economical forms of the sport. What many may not be aware of, however, is that on numerous Southland beaches (in Southern California, my surf-fishing outings primarily encompass the area from Los Angeles County beaches to the Mexican border), there are ample opportunities to engage in the classic sight-fishing scenario, in which you search out and cast to fish that present visual targets.

In my article “Corbinas in the Southern California Surf ” in the September/October 2008 issue of California Fly Fisher (this was followed up by two more pieces on the subject by my buddy Jeff Solis), I pointed out that one of the highlights of this fishery is the fact that you can often clearly pick corbinas out in the water mere feet from shore and present your fly in circumstances closely akin to wading a tropical flat in pursuit of bonefish. Recently, however my sight-fishing opportunities off the beach have expanded to include what are locally referred to as shovelnose sharks or guitarfish. In what follows I would like to share my experiences with both species and, I hope, interest you to give this kind of sight fishing a try.

For bait fishers, the shovelnose is far easier to catch than the corbina. When I was a youngster fishing the Manhattan, Hermosa, and Redondo Beach piers, shovelnose sharks were practically a guaranteed catch if you bottomed fished anchovies outside the surf line. Adopting the attitude of my more experienced senior anglers, I came to regard them as trash fish. They fought a lot harder than halibut, but the latter is the fish most pier regulars were targeting, and the shovelnoses were considered a nuisance.

However, when you target both corbinas and shovelnose sharks with artificials, the scenario is reversed. To the surprise of a number of Florida Keys guides, I’ve gone on record touting our West Coast corbina as a more challenging flyfishing target than even the revered permit. I base this on the fact that at least 50 percent of the permit to which I’ve cast have taken the fly. This is nowhere near the case with corbinas. In this respect, they are very similar to Hawaiian Island bonefish — be prepared for a preponderance of frustrating refusals. And with shovelnose sharks, the game is even more difficult. It’s been my experience that this prehistoriclooking creature is more challenging to entice with a fly than a corbina.

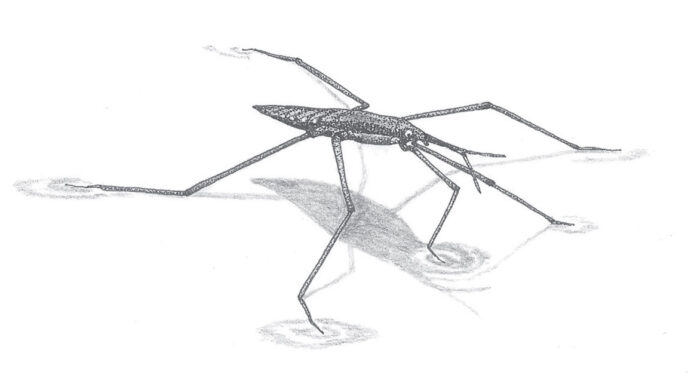

Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that biologically, the shovelnose is classed as a member of the ray family (its scientific designation is Rhinobatus productus), and in all my years of saltwater fishing with all modes of tackle, I have never known stingrays and such to show an affinity for artificial offerings. Shovelnoses and the like will readily consume a variety of prey such as marine worms, crabs, clams, shrimp, and baitfish, but show little interest in flies designed to replicate these dietary items. This decided preference for the real thing might be a function of their highly developed sensory system. These creatures may look like throwbacks to the age of the dinosaurs, but their vision and balance systems are state of the art.

In the past 45 years or so, I’ve taken only about three rays on the fly, and they were not intentional catches. Furthermore, in no instance was the fly actually in the fish’s mouth, which is located on the ventral side of the body. This has also been the case with the shovelnose sharks I’ve sight cast to off the beach. Even though the fly was hooked in close proximity to the mouth, it was not actually in it, which raises the question whether these can be considered a legitimate catch and not mere instances of snagging fish.

Noted fly tyer and close friend Bob Popovics has had similar experiences with cow rays on the Jersey shore. These rays battle like no striper ever could, and Bob wanted to share his experiences with others. But he did not want to promote a practice that might be construed as snagging, so he made an inquiry to a Florida marine facility, where he was assured that due to the sensory system governing their feeding practices, rays caught with the fly in close proximity to the mouth can be regarded as “legal” catches.

Apparently, the ray (and the shovelnose) can see the fly and also detect movement. Similar to halibut, which often lie flat on the bottom, the shovelnose and the ray are keenly aware of what is going around them, with their sensory facilities finely tuned to vision, smell, and movement. With the shovelnose, the takes that I’ve observed involve a sudden turn or lurch of the fish’s triangular head, followed by all the line in my stripping basket rocketing through the rod guides. Unlike bait presentations, where the sense of smell is often what first draws the fish to the offering, in the case of flies, it is the movement.

I have had shovelnoses track a fly only a couple of feet. Then they either make an attempt to take it or suddenly veer off and swim away. The hookup often occurs right in the nose area, not in the mouth cavity on the underside, which lies approximately four inches or so from the snout. Obviously, nailing one in the tail area would clearly be regarded as snagging, but I’ll leave it to others to debate whether or not catches like the one I’ve depicted violate fly-fishing ethics.

The northernmost range for the shovelnose is touted as San Francisco, and its range extends southward into the Sea of Cortez. In the six years I spent in the Bay Area, I never encountered any on the local beaches, but it’s been an entirely different story since I’ve relocated to the southern part of the state. The San Diego County beaches where I spend most of my time prowling the surf seem to have an abundance of this species. On one stretch, in a two-hour period, I spotted 21 shovelnose sharks on an ebbing tide. They ranged in size from foot-long juveniles to 36-inch-plus mature adults. Shovelnoses approaching the three-foot mark will give a good account of themselves and can be into your backing before you know it. They often tend to hug the bottom like a big halibut, and on light fly tackle (I usually opt for 6-weight outfits and 8-to-10pound-test tippets), you have to finesse them to the point where you can grab the tail section and slide them up the beach to remove the fly. If you are barefoot, do not step on the dorsal area to try to subdue one. They have thorny projections from approximately the midline to the tail section that could easily puncture flesh. I know of no instances where anyone got bitten by a shovelnose, and given the position of the mouth and their dentition, at is highly unlikely.

If I were asked to give a one-sentence description of what it is like to sight fish corbinas and shovelnose sharks in the Southern California surf, I would simply characterize it as a very low-percentage game. First off, fishing the West Coast surf with any tackle, including bait, is normally not the sort of endeavor in which you are likely to experience a great deal of action. The mindset of Northwest steelheaders, who know they target “the “fish of a thousand casts,” is appropriate for sight fishing the surf, as well.

Second, because you’re casting only to fish you can actually see, you significantly reduce your chances of hooking up, because you may have missed fish that would take your fly, even if you didn’t see them. So why not cast repeatedly? As experienced bonefish guides well know, the problem with this is that you may find yourself way out of position when you do spot a fish to which you want to present the fly. Additionally, you might spook fish you didn’t initially see and ruin your chances for a stealthy presentation. When I walk the beach with someone who is new to this game, I stress that the key virtue is to have patience. Even though you spotted fish the previous day under similar conditions and are confident fish will show, you have to be willing to take the necessary time (I’ve often waited a couple of hours) for them to do so. Most anglers agree when they first spot a target that the wait was worth it. Even those who have been privileged to sight fish distant locales for glamour species such as bonefish and permit are enthusiastically captivated when they see a corbina meandering along the shoreline in inches of water on a beach that may be only a few miles from where they live. Personally, I wish I could spend all my days sight fishing for species such as bones, permit, tarpon, and redfish. I cannot, but especially in the case of corbinas (which bear a slight resemblance to bonefish and reds), the experience is mighty close, and during the warm-weather months of the summer through the fall, I do this on practically a daily basis.

Sight fishing is a challenging enterprise in every locale where it is practiced. Two obvious requirements are some degree of sunlight and clear water. In the surf, the latter can sometimes be difficult to encounter, and when you do, the window of visibility may be only a matter of seconds. The reason for this lies in the nature of water movement as it approaches the beachfront. As a wave breaks, foam forms on the surface, and until it clears, you can’t see anything.

And breaking waves can stir up the bottom, which makes trying to spot something akin to staring at jar of mud. The peculiar water currents in the surf line also present challenges. If you sight fish for trout in a river, you have to contend with current, but it is relatively constant and unidirectional. In contrast, in the surf, in a mere matter of yards, the direction of the current can be reversed. In one spot it may running to your right; walk a little, and you may find it sweeping your line, leader, and fly to the left.

Another issue not encountered in rivers is that water sweeps into shore and then rushes back out again. All this movement affects fish behavior and complicates your presentation efforts. I’ve seen shovelnose sharks lying on the sand with part of their dorsal areas exposed, but like corbinas, they are not going to let themselves get beached. The next wave of incoming water will have them scooting back to the surf line.

The most fun is when you can get them to take when they are lying in only inches of water, but this can be extremely difficult, because generally, they are more intent on returning to slightly deeper water and are not feeding. Their senses are tuned to the next rush of water to reduce their exposure, and feeding is just not a priority.

Even when everything is right, and you have your target in your sights, it will not remain that way for long, and you have to be spot-on ready for a presentation that factors in both the direction being taken by the fish and the effect that water movement will have on the fly. When possible, I like to try to place the fly roughly 10 feet or so in front of a corbina. For a shovelnose, I try to reduce this to a matter of inches. I’ve found that my best spotting and fishing opportunities begin at roughly two hours into the cycle of an outgoing tide.

In terms of tackle selection, as stated above, I generally opt for a 6weight outfit, and most fly fishers engaged in this game would probably agree with this choice. However, when it comes to selecting a fly line, I remain relatively isolated in my preference, even when sight fishing. I opt for lead-core shooting heads, a system I used over 40 years ago when I began fly fishing Southern California’s beaches. Over the ensuing years in this environment, I have fished practically every type of fly line manufactured, and for the conditions I face in the surf, I still fall back on lead-core heads. One major drawback is that they tend to kink, but when you get used to fishing them, that’s only a minor annoyance. On the other hand, they have a number of pluses, the most important of which is that they track better than any line in the surf ’s turbulence. With strong enough currents they’ll get swept along, too, but nowhere to the degree you experience with conventional fly lines. Given their relatively small diameter (the line I frequently use is Cortland’s Kerplunk, rated at 17-pound test), they cast into the wind more effectively, they keep even slightly weighted flies close to the bottom, they are simple to set up, and they are the least expensive line you can fish.

At first, you might think that a line like this spooks fish. Regardless of the line or its color, however, a poor presentation is going to scare off fish. With a 10-foot leader of 8-pound test, the lead-core line is relatively unobtrusive. For a 6-weight rod, I use a section I measure by spreading my arms out wide (this amounts to approximately 6 feet) four times, yielding a head roughly 24 feet in length. All you have to do is work out about an 8-inch section of lead core at each end of the braid, break it off, and tie a Surgeon’s Loop in the leadfree tag ends. The shooting line is looped to one end and the leader to the other — simplicity itself.

As with fly lines, there is a wide range of opinions regarding fly patterns. Though some have touted their own or maybe a friend’s creation as the hot pattern for corbinas, personally, I have not found fly patterns to matter much. A well-executed presentation is far more important. That said, a pattern that has scored successes with both corbinas and shovelnose sharks and that I now fish almost exclusively in the surf is a knockoff of a Hawaiian bonefish pattern, the Jiggy Bone Bug, created by Clayton Yee, co-owner of the Nervous Water Fly Fishers shop in Honolulu. The best step-by-step tying instructions are on the Hawaii Fly Page of his Web site, http://www.nervouswaterhawaii.com. Clay ties it on a 60-degree jig hook, and I’ve had excellent results in smaller sizes (6s and 4s) suitable for our Southland surf fishery, tied on jig hooks from The Fly Shop in Redding, California. Depending on conditions, you can use various size dumbbell eyes for weight; medium is the one I tie with most. As the Web site shows, the tail is made from marabou, and the body is wrapped with cactus chenille. Most of my color combinations for these materials range from tan to brown, approximating the color of sand crabs. Palmering a mallard flank feather around the head section adds a realistic effect.

This pattern meets all my requirements for the surf: it is nonfouling, durable, fairly quick to tie (palmering the mallard flank may require a little practice), and it catches fish as well as or better than anything I’ve used in the surf. You can fish it in a series of short, intermittent strips, similar to the method typically used for bonefish on the flats.

Of course, polarized glasses are an absolute must for sight fishing, and I never venture on to the beach without a stripping basket. Since this is primarily a warm-weather fishery, I generally forego waders. Bear in mind, however, that getting a little wet with the wind blowing can easily get you chilled. But all that is quickly forgotten when you do it right, and the surf gods favor you with a take that suddenly stops your fly and sends line ripping out through the guides. Topping this off is the fact that you have an eyewitness account of the whole event.